Brooklyn, New York

The girls both grin.

Such is the promise of Brooklyn Prospect Charter, which is using the model of school choice to break down neighborhood barriers and foster a more diverse student body.

But such an approach faces skeptics on both sides. On the one hand critics of charter schools say that far from advancing integration, they are a source of segregation. On the other hand, some advocates of school choice say that the model should stay focused on empowering parents and advancing student achievement — not integrating schools. Research on the issue is mixed, but past studies suggest that charter schools may exacerbate previously existing segregation within a district.

The new question in Brooklyn and beyond is whether integrated charter schools can successfully combine the benefits of parent choice with effective, high quality programs that would appeal to families of all backgrounds? If so, then they might manage something that has eluded much of the charter and traditional public school sector for decades — integration.

Halley Potter, a fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, says that integration was part of the original concept of charter schools, as envisioned by the late American Federation of Teachers President Al Shanker.

“Part of the [charter school] idea was that this would be breaking away from a neighborhood school model, enrolling students from a wider area and that could open up new opportunities for serving all different kinds of students together in the same school,” she told The 74.

Potter coauthored the 2014 book “A Smarter Charter”, which argues that charter schools should return to their roots and focus more on socioeconomic integration and teacher empowerment, as opposed to choice and competition — the dominant rhetoric now surrounding charters.

Brooklyn Prospect is part of a small group of charter schools now explicitly focusing on integration. The school, which serves grades K–12 at two Brooklyn campuses, one in Windsor Terrace, the other downtown, was founded in 2009 by Daniel Rubenstein. Brooklyn Prospect ensures an integrated setting via a weighted lottery: about one third of its students are economically disadvantaged and no racial group makes up a majority.

Visiting the school a few months ago, I was greeted by two seventh-grade students who described a strong, happy school community replete with great teachers, extracurriculars such as a filmmaking club, and classes like Mandarin Chinese.

Walking the hallways, I could see what they meant by “community:” Students of all different races could be seen working side-by-side or collaboratively in class. During that day’s lunch, students were randomly assigned seats in the cafeteria in order to foster bonding with peers with whom they might not typically interact. The 750-student school is also quite popular among parents who must navigate a waiting list, receiving 12 applications for each seat, according to the school.

Among the school’s biggest challenges are students coming in at different levels of achievement, says Rubenstein. The school offers an “embedded honors” program for high-achievers. This approach, which is open to any student, keeps kids in the same class, but offers additional meetings and projects for those wanting more challenging coursework.

“They view it as a completely separate class, but it is part of their standard work and it’s taught concurrently with their class,” said Rubenstein. Crucially, he explained, the approach eschews traditional school tracking systems, which divide kids based on academic ability, and can promote segregation between classes within the same school.

Rubenstein founded The Coalition of Diverse Charter Schools, a group of about 30 charter schools and networks across the country, that are deliberately “racially, culturally, and socioeconomically diverse.”

The Coalition argues, “Diverse charter schools promote equality by ensuring that students from different backgrounds have the same high quality educational opportunities.”

But does it work? Do students, like those at Brooklyn Prospect, really benefit from an integrated environment?

“We know from more than 40 years of research … that the socioeconomic composition of a school has a huge effect on children’s learning outcomes,” Potter said.

Indeed, there is strong evidence that integration makes a difference.

One study of Montgomery County, Maryland looked at low-income students who were randomly assigned to integrated public housing — and thus an integrated neighborhood school — and found that those students made large achievement gains in comparison to students who attended a more segregated school.

Evidence from the Charlotte–Mecklenburg district in North Carolina found that the end of its busing program in 2002 widened the achievement gap between black and white students. The researchers also linked the increased school segregation to rises in arrest and incarceration rates among men of color; this occurred despite efforts by the district to bring additional resources to segregated schools.1

National research has also found that the desegregation efforts of the 60s, 70s, and 80s — many brought about by court order — led to long-term benefits for African Americans in the form of greater income, better health outcomes, and lower incarceration rates.

Some studies suggest that the benefits of integration come as affluent, politically influential parents increase school spending, improving school quality. Other studies find that money isn’t the whole explanation, and some speculate that concentrating disadvantaged students in the same school simply makes the job of educators more challenging.

Potter acknowledges that there have been few, if any studies, looking specifically at integrated charter schools, which largely came onto the scene after the desegregation efforts of earlier decades.

At Brooklyn Prospect, the results, at least as measured by standardized reading and math test scores, are mixed. A measure of student growth from 2011–13 suggested that the school was about average in English and above average in math.2

More recent data shows that the school’s black, Hispanic, and low-income students perform about the same as students from similar backgrounds who attend surrounding neighborhood schools. Brooklyn Prospect’s white and more middle-class students score worse.

“A three-year look at the data shows that we have remained quite close to district proficiencies for white and non-low income students — sometimes a tiny bit higher, sometimes a tiny bit lower,” Brooklyn Prospect’s Deputy Executive Director Penny Marzulli said in an email. “We believe the numbers are really much too close to draw any conclusions about the quality of instruction for non-low-income students.”

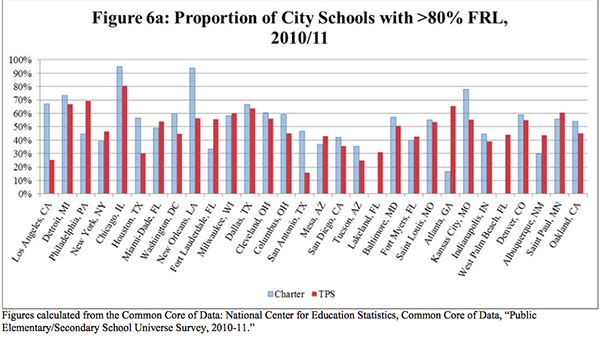

Some charter skeptics suggest that far from easing isolation, school choice is exacerbating it. A 2010 report from UCLA’s Civil Rights Projects, called “Choice Without Equity: Charter School Segregation and the Need for Civil Rights Standards,” says that the “charter sector continues to stratify students by race, class and possibly language.”

This is a hotly disputed issue among researchers. It is clear that many charter schools are highly segregated. But so are many traditional public schools. And charters are predominantly located in urban areas where school makeups mirror high degrees of housing segregation.

The relevant question may not be whether charters are segregated, but whether the existence of charters deepens existing segregation. The research is mixed on this question and depends a great deal on the location. In certain states, like North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Indianapolis, and Texas, charter schools are to some degree worsening segregation. But charters may be improving integration in cities like New York City and Little Rock, Arkansas.

An analysis of national data showed no correlation between an increase in charter school enrollment and an increase in racial segregation. A recent review of charter literature found that in most places charters and district schools experience largely similar degrees of racial and socioeconomic segregation — though “school choice decisions … tend to perpetuate and sometimes accentuate such segregation.”

Although some charter school advocates are embracing the push for integration, others are more skeptical.

“I don’t think [charter schools] exacerbate [segregation], I think white people do,” says Chris Stewart, the director of outreach and external affairs at Education Post. (Disclosure: The 74 sometimes partners with Education Post to share content.)

To Stewart, a former Minneapolis school board member and a charter school parent, even calling charter schools that predominantly serve one race “segregated” is fundamentally wrong.

“I don’t think that Howard University and Morehouse are segregated …. I don’t think when we say ‘segregation’ in historical context that we do anybody any favors by … conflating the government-sanctioned and endorsed forcing of people into suboptimal circumstances with the self-selection of people into affirming school environments that meet their cultural and home needs,” he said. “Those are two wildly different premises.”

Stewart worries that a focus on integration leads students to be “culturally stripped” of their racial identities. Moreover, he is skeptical that segregation will be successfully addressed anytime soon and sai African-American families can’t afford to wait.

“My bottom line is there are eight million black children in the United States that need to be educated,” Stewart said. “This criteria of ‘It has to be in an integrated environment’ seems like putting in place an unmovable object so that you can never get over it.”

He points out that in Wake County, North Carolina a widely heralded system of socioeconomic integration was stopped in its tracks by a group of school board members who campaigned on dismantling the program.3

“I can’t think of a lot of places in the United States where [school integration has] been … lasting and durable over long periods of time,” Stewart said.

For policymakers who want to boost integrated charter schools, there are several ways to make it easier. Charter schools that want to integrate can run carefully weighted lotteries that give certain students an advantage in order to ensure diverse enrollment.

More ambitious districts have created so-called “controlled choice” models, which use a combination of family preferences and student demographics to ensure integration across schools. This approach however can run into concerns from some who see this as limiting choice by assigning schools based on factors other than individual families’ preferences.

Districts and states can also consider how funding enters into the equation. Additional funding for high-poverty schools — like federal Title 1 dollars — may be necessary to help disadvantaged students, but it may also discourage the creation of integrated schools because they risk losing money if their enrollment becomes more affluent and, in some cases, more white.

Finally, charter integration may be impeded by attempts to ensure that charter schools don’t “cream skim” by requiring them to mirror the demographic mix of traditional public schools. That would mean that existing segregated schools that surround them could limit their ability to promote integration. (A bill to this effect was proposed recently by the New York State Assembly, but was not enacted.)

Rubenstein said that such a law would harm his school.

“In the good intention of trying to encourage more charter schools to [serve more] students with [special needs] and English-language learners … there is also a side effect of having a negative impact on schools that are truly integrated,” he said.

As American schools struggle to break free from issues of persistent segregation, classroom integration has re-entered the national conversation. And with housing also segregated, advocates like Potter believe that charter schools, with their lack of enrollment zones, should be part of the solution to the problem.

To her, expanding integrated charter schools is not only likely to increase achievement, but broaden families’ schooling options.

“I’m not sure in many cases [that] we have actually given families a full set of choices,” she said.

The nascent movement of charters now embracing integration suggests there’s something to that — and there may even be parent demand.

Interestingly, though, Rubenstein of Brooklyn Prospect, says parents generally don’t come for the integration: “Parents first and foremost care about quality.”

Stewart echoes that sentiment: “The moment that quality goes down, [parents] will leave.”

If policies and the commitment of charter operators can expand effective, integrated charter options, these focused schools of choice could well help foster a durable system of classroom integration that, to date, both charter and district schools have largely failed to provide.

1. There is now another effort to desegregate Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s schools, but it has met political resistance, with some arguing that charters are being used to avoid integrated schools. (back to story)

2. A comparable measure of growth for more recent years does not appear to exist. (back to story)

3. Recent research on the program found that it may have slightly improved test scores, while also reducing racial segregation relative to similar districts. (back to story)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)