Montclair, New Jersey

How one idyllic town became a hotbed of intrigue and accusation over assessments

On a December evening in a New Jersey high school auditorium, a show of political activism was in full display. The Montclair school board mulled a resolution requiring the district to give students who chose to boycott the state’s new standardized test other, positive things to do.

The resolution’s intent was clear: There would be no shame, no recrimination and definitely no consequences for refusing to sit for a test whose unpopularity was bubbling up all over the country.

That night in Montclair, well-spoken parents urged the board to greenlight the policy because the test, known as PARCC, put too much pressure on their children. Teachers donned matching union T-shirts and argued vigorously that they could assess their students better than any foolish test could.

The star of the night, a fourth-grader with a pink step stool, articulated their grievances simply: “I love to read. I love to write. I love to do math but I don’t like the PARCC,” the student read from her prepared remarks. “Why? Because it stinks.

Behind the scenes, other actors played their part too — a cadre of organizers who suddenly found themselves in the spotlight when hundreds and hundreds of emails were

made public this spring, revealing a sprawling web of influence and collaboration between the mayor’s office, a school board member, a community activist and the teachers union. On the other side of the fray an anonymous blogger with a keen eye for scandal surfaced— a savvy researcher with suspected financial backing out to expose who was pulling the levers on Montclair’s opt-out movement.

In a matter of months, Montclair’s boycott of PARCC had grown from a fringe activist cause into a heavy-hitting parental campaign with political clout. In the end, nearly 50 percent of Montclair’s roughly 6,700 students refused the test, a striking number even during what might be dubbed the Opt-Out Spring, when anti-test fervor spread from state to state.

Underlying this seemingly grassroots protest, however, is a story about how secretive operatives, education insiders and the elite turned one of America’s choicest suburbs into a textbook example of just how ugly the education reform wars can be.

Upper Montclair, New Jersey (Credit: Blondhairblueeyed,

Creative Commons)

“An aspirational town”

Just a short train ride from Manhattan, Montclair is the kind of place that attracts what’s known as influencers — media heavyweights, policy makers, bankers, lawyers, actors and writers. They come looking for a quaint, small-town feel, an easy commute to the city and a zip code with progressive cache.

“Montclair is an aspirational town,” said parent Marcus Walton, 43. “There is a mythology to it. There is the promise of opportunity.”

Part of the main drag — Bloomfield Avenue — is lined with chic boutiques, antique shops and trendy restaurants. The lovely Victorian homes that grace the sidewalks of exclusive Upper Montclair can easily sell for $1 million or more. But a short distance away, there are neighborhoods where the poverty level reaches 30 percent, according to the U.S. Census.

The town claims few major industries so residents fund the local schools and government. The average property tax bill in Montclair in 2014 was $17,175 — the 13th-highest in New Jersey, a state synonymous with steep taxes.

Montclair is diverse — more than a third of its residents are minorities. In 1977, the town started a new magnet program aimed at desegregating the school district after the state education commissioner agreed with a group of activists that the local government had been too slow to integrate its classrooms. Now, the district has a well-developed system of schools offering specialized curriculum that residents often brag about.

“Montclair prides itself on its diversity, but it was hard fought. It was not a natural process by any stretch of the imagination. People had to fight for acceptance,” said town historian Mike Farrelly. “We had demonstrations and disagreements and, quite frankly, we still do.”

There is a certain satisfaction in the school system here, particularly among well-to-do parents who favorably compare Montclair High School’s offerings to the private schools’ where their even more affluent neighbors send their children. Ninety percent of the 2014 graduates enrolled in some form of higher education, including Ivy League colleges.

Last year, most Montclair students were considered proficient in English language arts and math on the state standardized test. But in only two grades were more than 90 percent of students deemed proficient in English while no grades met that benchmark in mathematics.

In report cards compiled by the state Department of Education, only four out of 11 schools were considered above average in academic achievement compared to other New Jersey schools with similar demographics. Comparable data for one school was not available.

The district also suffers from a persistent achievement gap. During the 2011-12 school year, about 45 black seniors had GPAs in the top 50 percent of their class, compared to 158 white seniors. Meanwhile, the grades of 149 black seniors ranked in the bottom half of their class compared to only 57 white seniors occupying that rung, according to a recently released report. In 2014-15, whites accounted for 49 percent of the high school enrollment but 72 percent of the Advanced Placement classes while blacks made up 35 percent of the student body but only 11 percent of AP classes.

The achievement gap between Montclair’s black and white high-schoolers and the underperformance of many of its elementary schools are thorny issues in this town of roughly 39,000 residents where the average median income is $96,503.

“It suddenly struck me that the same battles being playing out elsewhere were being played back in my hometown (and) were affecting my kids directly,” said Sam Cole, a Montclair parent of three children and chair of the governing board of Success Academy Charter Schools in New York City.

“I was unhappy with the quality of education. The teaching quality was very inconsistent.”

Sean Spiller, a Montclair councilman and treasurer and secretary for the New Jersey Education Association, the state’s largest teachers union, offers a competing vision for what local schools are facing: “I think that for very many of us, we know, by all accounts, New Jersey schools are best in the nation but we have things we need to work on and they’re directly tied to resources and other things that our students and our families need to be successful. Education of a student doesn’t begin and end (with) the start of a bell of school and the end bell.”

A well-orchestrated backlash

The divide between Spiller and Cole echoes a larger battle in Montclair being fought between two groups with names so alike it would be easy to confuse them. Montclair Cares About Schools started some three years ago in opposition to increased standardized testing in the district’s lower grades.

Montclair Kids First was born, its founders say, out of frustration over the way Montclair Cares About Schools had taken over the education debate in town: “We can’t have the conversation: Is there a better way?” said Linda Bowers, a mom who co-chairs a parent group at the high school. “If you ask the question, you are labeled something.”

Two organizations in the same school district with competing visions for its mission is nothing new, but Montclair’s conflict ticked over to the next level this spring with the release of reams of emails going back two years — emails sought under public records law by Montclair Kids First about the working communications of Montclair Cares About Schools.

(See complete MontclairKidsFirst.org email archive)

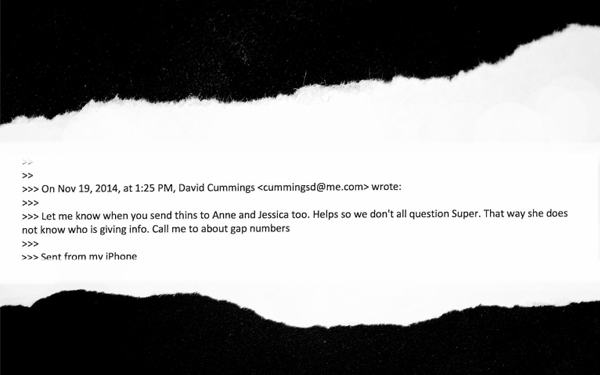

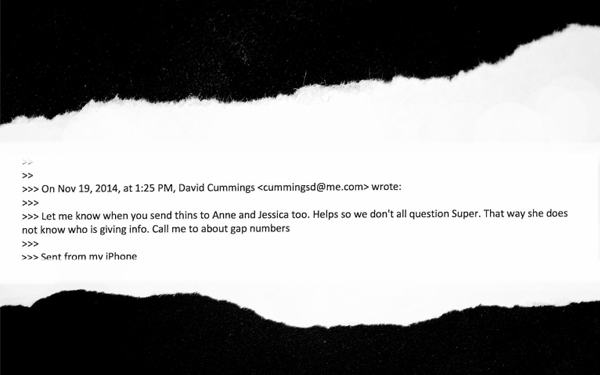

The two major figures in the emails are parent Michelle Fine, a psychology and urban education professor at the City University of New York, who emerges as the force turning anti-test sentiment into widespread action, and David Cummings, her main ally on the Montclair Board of Education. Many of the emails were sent from Fine’s CUNY “.edu” email account and many people’s names were redacted after they told CUNY they feared retaliation.

The emails reveal where and how pressure was being applied to the decision-makers in town along with a level of vindictiveness and sometime-paranoia among the combatants. What they document:

- Fine and other activists exerting influence over the mayor on who to appoint to the school board and strategizing with officials about how best to fuel the testing boycott and upend the superintendent’s agenda.

- The mayor pressuring the school board leadership to pass a resolution providing extra support for students who opted out.

- Cummings going to extraordinary lengths not just to express support for those forgoing the test but aggressively trying to encourage others to join the “opt-out” ranks.

- Fine and others regularly monitoring and angling for media coverage, in hopes of advancing “opt-out” talking points.

“It was just this really well-orchestrated, well-planned attack. It wasn’t this kind of ad hoc grassroots (group of ) parents,” said Shelly Lombard, a former school board member who belongs to Montclair Kids First. “Everybody had a tie and vested interest in education as it currently exists.”

Montclair Kids First posted the trove of emails on its web site. But Fine dismisses any notion they constitute a smoking gun.

“I think the emails were disappointing (for Montclair Kids First),” she said. “They were looking for conspiracy and they found a bit of cursing.”

Michelle Fine (Courtesy of City University of New York)

Spiller, the Montclair councilman and union leader, said Montclair Cares About Schools recruited help from whatever quarter it could in fighting for a worthwhile cause. After all, that’s how political movements work, he said.

“As part of effectuating change in anything you do, of course, they are going to reach out to anyone they can to try and get the schools back to a place where they thought (they) would be successful,” he said.

Montclair Kids First also surely has backers with agendas, although the group has not made its donors public. Local resident Donald Katz, the CEO of Newark-based Audible, one of the largest audio-publishing companies in the world, had promised financial support to the organization. (Katz’s wife, Leslie Larson, once sat on the school board.)

The group, which says it seeks to support disadvantaged youth through supplemental services while also demanding “teacher effectiveness,” accountability and a challenging curriculum, alleged in a complaint that there was a conflict when the mayor tapped Spiller to serve on the Montclair Board of School Estimate. The board approves expenditures tied to teaching, Spiller points out, but does not OK the Montclair teachers contract.

“I disagree completely with their contention that it is a conflict of interest,” Spiller said. “If you are gonna talk about some type of conflict, there has to be some type of benefit that comes from it.”

The seeds of discontent

The political fissure that erupted in Montclair with the publication of the emails had its start in 2012. In August that year, Gov. Chris Christie signed a bill that seriously weakened teacher tenure. After being negatively evaluated for two years in a row, the bill stated, teachers could now see their tenure revoked. Then last school year, for the first time, New Jersey students took PARCC, a computerized test based on the more rigorous Common Core standards.

The stakes had changed.

“Now it matters,” Larson, the former school board member and Montclair Kids First member, said. “Now they are saying if your kids don’t score well it’s going to reflect (badly) on your evaluation.” And possibly endanger your tenure.

In fall 2012, Penny MacCormack stepped onto the stage as Montclair’s new schools chief, one with a strong pro-testing philosophy. MacCormack had spent more than two decades in education, working her way up from classroom teacher to chief academic officer of the Hartford (Conn.) Public Schools. She later became chief academic officer for the New Jersey Department of Education, before taking the job in Montclair. She also participated in the Broad Superintendents Academy run by the Broad Center for the Management of School Systems in Los Angeles— a reform-oriented training program.

“I believe in the idea of continuous improvement,” she said during her first month on the job. “Even a successful organization can improve and should.”

But MacCormack’s ideas about what constituted improvement would meet resistance in New Jersey. Not only did some think her hiring and contract negotiations lacked community involvement, they saw her as pushing through reforms without consensus.

Former Monclair Schools Superintendent Penny MacCormack. (Courtesy of Montclair Public Schools)

“(MacCormack’s) model was to come in and say everything was doing terribly and blow it up. I think the community then had a backlash to that,” said Spiller.

“Like everywhere, we always want to improve and there are things we need to improve but this is not the way to do it. And we should have talked about this as a community before it was unilaterally imposed.”

In June 2013, MacCormack unveiled a strategic vision for the district that would include among other things quarterly standardized assessments, starting with the 2013-14 academic year. The idea was that students with different teachers would all take identical tests to help the district identify which ones were struggling.

That was the moment Montclair Cares About Schools drummed up intense opposition to the plan, arguing the heavy focus on testing was misplaced — and diminished what was best about Montclair. A change.org petition garnered 570 signatures from parents and activists. “We understand that our district must comply with state and federal testing requirements,” it stated. “However, the Strategic Plan currently under consideration puts an undue emphasis on data-driven instruction above and beyond these requirements at the expense of the creativity and energy that are at the core of Montclair’s personality.”

Some in Montclair saw the rejection of quarterly assessments as a lost opportunity to address the inconsistency among teachers. Wealthy families knew how to work the system to secure the better teachers or the best classes, leaving less privileged kids with the worst of both, they argued.

“That was the first thing she tried to implement and people went berserk,” said Lombard. “And that’s unfortunate because…I want to make sure that whatever school I’m at that my kid is getting the same high quality instruction.”

The Montclair school board voted to approve the strategic plan. Teachers—under the district’s direction — developed curriculum and the content of the new assessments at a cost of about $490,000, MacCormack told The Star-Ledger. But not a single student would take them.

Anonymous forces

In October 2013, days before the new exams were to be given, copies of the tests showed up on a public website. An online critic and Twitter account named “Assessmentgate” quickly popped up and began taking shots at MacCormack.

“MacCormack’s supporters: embracing, enabling, and celebrating mediocrity,” read one tweet. Another: “There have been a number of PENNYFAILS since she’s become the SUP.”

MacCormack shelved the exams and instructed each school to use the outed tests as a model to create their own, according to The Star-Ledger.

"The loss here is consistency from school to school," MacCormack told the newspaper. "We would have learned a lot from the assessment. The plan we have in place will allow us to have a level of learning that is important, but it won’t give us the district-wide level of learning I was hoping for."

The Board of Education, meanwhile, launched an investigation. The district attempted to subpoena Google to determine the identity of the individual who used the Gmail address for the anonymous posts. But a judge halted the subpoena after the ACLU, who was representing the Assessmentgate critic, got involved. The two sides eventually reached a settlement in which the blogger would answer the district’s questions anonymously but the district would not seek his or her identity, according to Patch.com. It’s unclear if that “don’t ask, don’t tell” questioning ever took place.

In December 2013, the district was prevented from completing a forensic computer investigation into who leaked the test when the Montclair Township Council voted not to allow school officials access to their shared servers.

Into this hothouse of conspiracy and suspicion entered a second anonymous blogger, this one called Montclair Schools Watch. In its inaugural April 2014 post, Montclair Schools Watch said its purpose was to spark “productive dialogue” around education issues. Since then, the blogger has released a steady flow of posts critical of the opt-out movement and its players, Montclair Cares About Schools and the local teachers union, the Montclair Education Association.

In one recent post, Montclair Schools Watch alleges Fine is connected to a group that embraces “right wing” racism and bigotry. In another, the blog criticizes Fine and other members of Montclair Cares About Schools for participating in a forum on education and testing reforms in Illinois.

“One of the things that frustrates us most about the Montclair debate is the way that our schools are being used as a proxy for the national fights these activists are taking on,” the blogger wrote. “Their struggle isn’t about our schools here in Montclair at all – it’s about their broader national agenda and national anti-school reform activism.”

Other posts were more personal, such as reporting that the head of the Montclair teachers union had trouble paying her taxes. The blogger stated that a national research firm was looking into Montclair officials and politicians “to dig up dirt,” an apparent signal that an outside entity with money was diving into their background.

The blogger didn’t respond when emailed by The Seventy Four asking about his or her identity or funding, but said the blog was meant to counter Montclair Cares About Schools’ “constant attacks” on the district. The blogger has made the most out of Fine’s and Cummings’ emails and went so far as to publicly accuse a member of Montclair Cares About Schools of orchestrating Assessmentgate. Later, the blogger acknowledged that charge might not be true and a separate state investigation found that the leak likely came from inside the district.

All the intrigue has left residents to wonder if forces beyond Montclair are now part of the script.

“What’s the driver of some of these entities?”asked Walton.

Opt-out catches fire

By last fall, the New Jersey opt-out movement began picking up serious steam. Montclair Cares About Schools and other groups were organizing “Take the PARCC” events designed to allow parents to explore the test but also discuss its implications. Activists in other municipalities began to form their own “Cares About Schools” groups.

In Montclair, neighbors urgently debated PARCC on Facebook and blogs, at parent gatherings and in letters to the editors in The Montclair Times.

“There is such an emphasis on testing,” said Montclair parent Myrna Marcarian, who decided her special needs son would skip the test because it would be too anxiety-provoking.

But Montclair parent George Bennett said the opt-out movement was a distraction from the real issues of poor performance facing the district.

“When you have urban communities that (are) outperforming them in every single category that says there is a problem,” Bennett said, comparing certain high-performing Newark charter schools to some Montclair schools.

Reporters were catching on to the debate too. Montclair parents who had decided to opt-out of PARCC made their way onto television networks and nationally recognized blogs.

“My kids spend six hours, seven hours in school a day and they spend a majority of that time preparing for this test,” Montclair parent Beth Dreifach told CBS.

But members of Montclair Kids First say the situation had swung so far in the other direction that the students who were opting into the tests were the ones being stigmatized. Teachers were scheduling review sessions for another test during PARCC, putting the kids who took the standardized exam at a disadvantage.

“The kids who actually went to the PARCC test got penalized,” said Bowers, who said her son was marked absent when he took the test.

Meanwhile, the swelling opt-out movement and its impact had reached state and federal levels. State education Commissioner David Hespe wondered if New Jersey would be in compliance if it passed legislation allowing parents to opt their children out of the tests. The U.S. Department of Education replied by reiterating that all students were required to take the tests and that at least 95 percent needed to for schools to make their annual yearly progress goals. Failure to follow the rules could place some funding “in jeopardy,” federal officials said.

“The bottom line is that the law requires all students to be tested, and failure to take the test ultimately hurts kids, especially those who are most vulnerable,” state education department spokesman David Saenz said in a statement.

“That is why it’s unfortunate that some organizations have encouraged parents to refuse taking the test, and have misled parents by suggesting there are no consequences.”

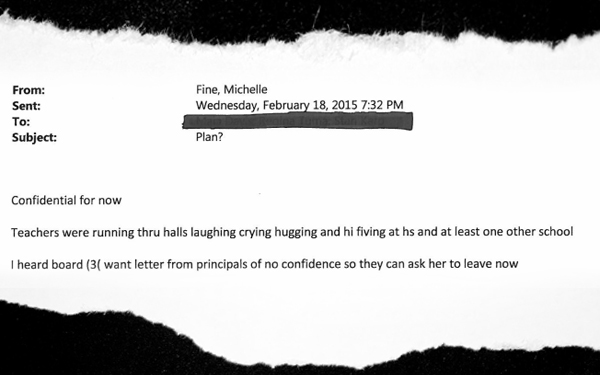

In February, the New Jersey Education Association announced a six-week television and web advertising campaign against PARCC. That same month, MacCormack, after three years spent trying to bring more testing to Montclair, resigned.

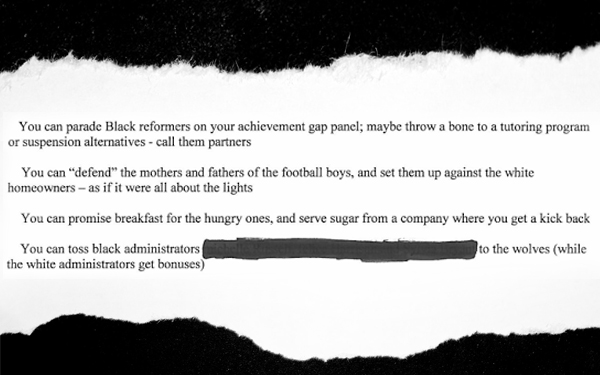

One of Fine’s emails about her exit has a “Ding Dong, the witch is dead” quality.

“Confidential for now,” the professor writes. “Teachers were running thru the halls laughing crying hugging and hi fiving at hs and at least one other school.”

MacCormack now works in New York City as the chief academic officer of the Administrative Council on Undergraduate Education, according to her LinkedIn page.

“Sorry,” she said before hanging up on a reporter from The Seventy Four who called to ask her about her time in Montclair.

Black face/white profit

By last autumn, the rhetoric among the activists in the emails had strayed from education policy to vilification. In one of the stranger moments, Fine impersonates the voice of 19th-century African-American scholar W.E.B. DuBois to accuse the other side of masking their desire to make money as concern for minority children. She entitled it “Letter to Montclair.”

“Black face/white profit?,” she writes in October 2014. “How many ways can you use black people to hide the upward redistribution of public dollars into private white pockets of corporations, elites and administrators who are carpet bagging through Montclair?”

Fine said she adopted DuBois’ voice after an academic career devoted to studying inequality.

Around this same time, Montclair Cares About Schools members were closely monitoring news reports and online comments and angling for sympathetic coverage, the emails show. They were also targeting political leaders, primarily Mayor Robert Jackson and Cummings, the school board member.

After Fine sends information to Cummings about math teachers being pulled out of class for a PARCC meeting, Cummings emails her back that they should better plan how to challenge the superintendent.

“Let me know when you send things to (board members) Anne (Mernin) and Jessica (de Koninck) too,” Cummings says in November 2014. “Helps so we don’t all question Super. That way she does not know who is giving info.”

A few months later in February, Fine emails Cummings, de Koninck and Mernin about her concerns about technology and the PARCC. Cummings is at first unsure about who is on the email chain but then says, “I get it. Oh, I thought you sent that email to the entire board.” Fine responds, “no just to those able/willing to have an open conversation.”

These and other exchanges between Fine and Cummings, Montclair Schools Watch alleges, violate state ethics rules requiring school board members to remain independent of special interests. Cummings declined to address the allegations. Fine said that she often emailed all the the board members but it just so happened to be Cummings, de Koninck and Mernin who responded.

“They can’t make the case I was colluding with Cummings,” she said.

Last November, Fine also used her relationship with the mayor to try and influence who would be appointed to the school board. “We are thrilled to submit for your consideration the (name redacted), an educator, long time member of the Montclair community…She would be fantastic,” Fine writes to Jackson. “She and (redacted name) I know 2 is greedy…but (name redacted) also has strong community support as well as Montclair State University connections, deep historic connection to pre-k, strong ties with Head Start.”

Fine later jokes about receiving a commission for the recruitment help and thanks Jackson for doing his job with integrity.

Fine said several groups submitted recommendations for school board appointments after the mayor asked for them during a public meeting.

But Fine’s efforts to lobby the mayor would continue. Two days after sending her school board suggestions, on November 5, 2014, she writes to Jackson about a meeting she is organizing between him and school district staff.

“Anybody who asked the mayor to meet with him, he met with,” Fine said. Jackson did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Several months later, on February 15, Fine sent around an agenda for what appears to be a another meeting with the mayor on topics including the budget, the opt-out movement and “threats” against teachers and activists. The recipients have been redacted but Fine is frank with them about her plans for Penny MacCormack.

“Buying out the superintendent and her cronies — NOW,” Fine says.

‘Who is running this town?’

Back to that December board meeting in the high school auditorium and the Montclair Board of Education taking its first step toward directing MacCormack to provide students opting out of PARCC with “educationally appropriate and non-punitive responses.” Emails among public officials about this policy reveal just how much clout the opt-out movement had amassed by the end of 2014.

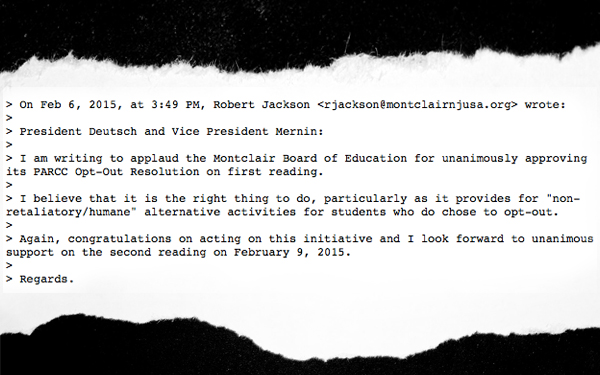

In one February email exchange obtained by The Seventy Four through a public records request, the mayor writes what appears to be a simple congratulatory missive to school board President David Deutsch and Vice President Anne Mernin. But the timing of the emails suggest the mayor’s not-so-subtle intent was to pressure the school board to vote after he himself was pressured by the community.

Jackson’s February 6 email came after the school board gave preliminary — first read — approval to the opt-out policy but three days prior to the final OK. “I am writing to applaud the Montclair Board of Education for unanimously approving its PARCC Opt-Out Resolution on first reading. I believe that it is the right thing to do, particularly as it provides for ‘non-retaliatory/humane’ alternative activities for students who do chose to opt-out,” Jackson writes. “Again, congratulations on acting on this initiative and I look forward to unanimous support on the second reading on February 9, 2015.”

For anyone who received the email, the mayor’s marching orders were loud and clear: He expected board members to vote yes on Feb. 9.

All of them.

The mayor’s urging of the board to express unwavering support of opt-out students came after community members asked Jackson and Councilman Sean Spiller to proclaim publicly that parents should be supported if they didn’t want their children to take the PARCC. As the emails show, the same citizens then allegedly grew testy when Spiller seemed reluctant.

“We then asked who is running this town? We wanted to know because we pay taxes, live here and send our children to public school,” one unidentified e-mailer tells Fine. “It is imperative that the Mayor’s office NOW gets flooded with short, pithy letters expressing the community’s fear of retaliatory actions, questioning the secrecy of the BOE on this matter of Opt-Out and refusals and how their child will be treated…”

Not long after, the mayor emailed the school board demanding action.

Lombard, the former board member who belongs to Montclair Kids First, said she’s never seen a mayor pressure the board so forcefully. “I’ve been on the board for nine years. I know the last couple of mayors really didn’t get involved telling the board how to vote,” Lombard said. “I don’t recall them ever sending me anything about a vote and which way they thought it should go.”

Once the board passed the resolution, Cummings, the board member in close contact with Fine, set out to make sure every parent in Montclair knew about it. He questioned MacCormack whether the district was going to alert parents to the opt-out deadline and whether a district-wide email should be sent to every family telling them the board had adopted an opt-out friendly policy.

“Do we need to consider families who do not have computers? Do we consider families who have been told their children must take the test?” he wrote.

MacCormack pushed back, saying it would go on the district web site and the principals would put it in their newsletters but she had no intention of sending an email blast unless explicitly told to do so by the board. Cummings then turned to the board, asking the president to poll the members about whether the superintendent should be directed to send the mass email.

“Do we have an obligation as a governing body to make sure parents are informed of their rights regarding something as important as the PARCC?” he wrote.

Turns out most Montclair parents didn’t need the email. More than 47 percent of local students opted out of the exam, including an overwhelming 79 percent of Montclair High School students. By contrast, 3.8 percent of New Jersey students in grades 3-6 opted out while 7 percent of 9th-graders and 14.5 percent of 11th-graders did, according to state data.

A preliminary analysis of neighboring New York’s experience by the Brookings Institute’s

Brown Center on Education Policy found two interesting factors contributing to opt-out: Relatively affluent districts tended to opt out more than poorer districts. However, once the poverty factor is taken out of the equation, districts with lower test scores shunned the tests more.

Parents attend a June Montclair Board of Education meeting. (Credit: Naomi Nix)

Protecting opt-out reaches Congress

Several months have passed since the PARCC boycott and the idea that opt-out should be protected as a matter of policy, or even law, has grown far beyond Montclair. The National Education Association, the country’s largest teachers union, is moving toward posting model legislation on its web site guiding all districts on how to craft non-punitive opt-out policies. Oregon schools will now notify parents twice a year of their opt-out rights. Congress, as part of its slugfest reauthorization of No Child Left Behind, is weighing an amendment allowing parents to opt their children out of standardized tests without penalty to their school. The existing 95-percent-participation-or-else rule would be no more.

Meanwhile in Montclair, the two opposing groups have not let up in their quest to win the educational hearts and minds of their sought-after town. Letters to the editor and blog posts proliferate, Montclair Cares About Schools remains highly active on social media and Montclair Kids First dramatically announced it planned to provide a free Internet hotspot device to every lower-income student in town.

“A child’s academic success should never be determined by his or her economic status,” group member Sam Cole said. “ A digital, economic and academic divide has existed in Montclair for years and we must work together to address this issue head on.”

The material remains rich enough for a narrated video reading of Fine’s emails to pop up on YouTube — there’s also an online petition now circulating in support of Fine — and for education scholar and testing uber-foe Diane Ravitch to weigh in on Montclair, calling it a “clash of David and Goliath!” on her blog.

No-nonsense veteran superintendent Ronald Bolandi, who came out of retirement to replace MacCormack, is looking to take it all down a notch. He’s already indicated he won’t get caught up in the larger power struggles that have consumed the district.

“The next two years that I’m here I’m gonna try to do the best I can…to get you ready for whomever will take this (position) in the future,” he told a small audience at the June school meeting. “I won’t fight unless it’s good for your kids. I won’t create a lot of drama.”

That would be a change for Montclair.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)