Analysis: Which Bothers Randi Weingarten More — Segregation or School Choice?

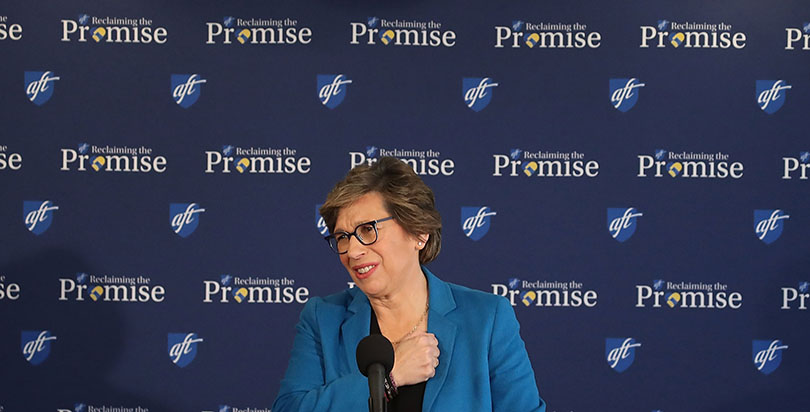

In a fervent speech to union activists attending the AFT Teach conference in Washington, D.C., Weingarten condemned the Trump Administration’s agenda to expand the use of vouchers that can be used for children to attend private schools.

“Vouchers increase racial and economic segregation,” Weingarten said, then tied vouchers to the wider aim of eliminating public education.

“Make no mistake,” she continued. “This use of privatization, coupled with disinvestment, are only slightly more polite cousins of segregation. We are in the same fight, against the same forces that are keeping the same children from getting the public education they need and deserve.”

Choice advocates were outraged and quick to respond.

"The hypocrisy that’s coming out of the mouth of Randi Weingarten reeks,” said Kevin Chavous of the American Federation for Children. “In her comments she has spat on the face of every African-American and Hispanic child who’s trapped in a school that doesn’t serve them well.”

Weingarten dismissed the outcry as “completely ideological, with personal invectives thrown at me.”

In the past two weeks, both support and criticism of Weingarten have centered on whether or not school vouchers actually increase segregation. A different question is whether or not Weingarten’s broadsides against vouchers, privatization, and disinvestment have anything to do with fighting segregation.

Elsewhere in the speech Weingarten recounted her joint visit to the public schools in Van Wert, Ohio, with U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. Weingarten chose that particular district because “these are the schools I wanted Betsy DeVos to see — public schools in the heart of the heart of America.”

“The people of Van Wert are proud of their public schools,” she said. “They’ve invested in pre-K and project-based learning. They have a nationally recognized robotics team and a community school program that helps at-risk kids graduate. Ninety-six percent of students in the district graduate from high school.”

Those are things to be proud of. But in a speech condemning segregation, Weingarten failed to mention another facet of Van Wert public schools: Out of 1,991 students, just 18 are African Americans. Not 18 percent — 18 students.

Just 30 miles down the road from Van Wert are the Lima City Schools. Their student population is 40 percent African-American, and they are not doing nearly so well. On the six measures of student achievement the state of Ohio uses to grade its public schools, the Lima City schools received five Fs and a D.

That’s not to say Weingarten has no familiarity with segregated schools. She was introduced for this speech by Claudia Marte, a former student of Weingarten’s when she taught at Clara Barton High School in New York in the early 1990s. Enrollment figures for those years aren’t available online, but a decade later, in 2003, the student body was 85 percent black and 3 percent white.

“How can you be indifferent when you hear from someone like Claudia?” Weingarten said.

For the most part, the public school system dictates the school each student will attend based on geographic boundaries. Some school districts even employ “border patrols” to ensure that only legal residents attend certain desirable schools. Segregated neighborhoods usually lead to segregated schools, so where one chooses or can afford to live will often determine whether one’s child will attend a school with a diverse student body, or one where a single race is the large majority.

Weingarten owns a home in East Hampton, New York, near the easternmost edge of Long Island. The median house value there is more than $1 million. The community is 86 percent white and 0.7 percent African-American.

If Weingarten had school-age children, there is an elementary, middle, and high school they could hypothetically attend. The combined enrollment of the three schools is 1,807 students. Only 68 students (3.7 percent) are African Americans.

Weingarten also owns a co-op in New York City’s Inwood neighborhood on the northern tip of Manhattan. The area was profiled in an article last year headlined “Inwood Is Actually Two Neighborhoods Divided by Race, Class and Broadway.” The author notes that while “both sides of the neighborhood are predominantly Latino, close to 90 percent of the area’s white population lives in West Inwood.” The locals refer to West Inwood as “Little Connecticut.”

“Residents east of Broadway have said for years that they face serious impediments when it comes to accessing information, police attention and other resources — which they blame on race, language and class differences with their western counterparts,” the article states.

Weingarten’s co-op is in West Inwood.

The combined enrollment of the three schools closest to the home she owns totals 1,085 students, of whom 73, or 6.7 percent, are African Americans.

For comparison purposes, African Americans comprise 27 percent of New York City Public Schools enrollment. Only 15 percent of city students are white.

Weingarten certainly opposes segregation, but her fire and determination are reserved for the segregation she sees in non-union schools — not in traditional public schools or her daily life. If we are to fight segregation and institutional racism, we cannot allow people to use union cards as a shield.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)