Analysis — The Future of School Governance: How Will Innovative Education Systems Balance a Need for Experimentation With a Parent’s Right to Make Informed Choices?

This essay also appeared in CRPE’s 25th anniversary collection, Thinking Forward: New Ideas for a New Era of Public Education

A local public education system built for personalization and rapid adjustment to workforce demands must be open to innovation and make full use of learning opportunities outside of conventional schools. But it can’t be so atomized, chaotic, or dominated by irresponsible providers that families are unable to make informed choices for their children. Families need a comprehensible set of options and information about likely results for students, and communities need options that prepare young people for jobs that are likely to exist.

However, the need for some order must not drive out innovation and responsiveness to change. Students must be free to pursue — and providers free to offer — learning experiences that community leaders might not understand or prefer.

How to balance these conflicting needs? This essay sketches an approach to local governance that is consistent with openness to innovation and responsiveness to the demand for knowledge and skills, yet works to preserve informed choice and equity. Not all localities that aspire to nimbleness will adopt the principles described here, but they will likely find that current governance arrangements neither promote nimbleness nor truly protect the interests of children, families, or the community.

Adopting light-touch governance

A nimble system of public education in any locality will need some governance. Mechanisms for matching students with schools and protecting them against negligent providers will depend primarily on information and choice — schools choosing vendors and curating pathways, students choosing among instructional experiences and joining pathways, pathway organizers demanding quality experiences from providers of instruction and hands-on learning, and colleges and universities valuing or disregarding what students learn on some pathways.

Local leadership, whether in the public sector or (most likely) in private-public collaboration, must be able to set priorities, attract the most effective schools and learning providers to operate locally, protect students from fraud and discrimination, and make sure learning providers don’t provide false information about the effectiveness of their programs or collude to keep out providers with new ideas.

We have written elsewhere about a “constitutional” system of local public governance, in which entities with oversight responsibility are not empowered to operate any schools or employ any teachers. By not operating schools or employing teachers, local governing bodies (which we call Community Education Councils, or CECs) would not encounter conflicts of interest. Their sole job would be to ensure that students can choose from a broad enough range of quality learning options to leave school with multiple postsecondary education and career opportunities, and that the community’s labor force is widely capable.

In the version we initially formulated, local CECs would not have overseen postsecondary education, career pathways, and adult reskilling. However, local governance for the adaptive, personalized system described in the other essays in this collection must extend beyond schools that provide all instructional experiences. Local governance must also ensure that students have quality choices among specialized learning experiences, as well as career pathways sponsored by combinations of schools, businesses, higher education institutions, and vendors that operate in many localities. To tap the expertise of employers and entrepreneurs, CECs would include individuals from established businesses, innovative and high-tech companies, higher education, and minority enterprises. These individuals, though appointed, would serve as equals alongside a number of elected public representatives. Our essay on funding suggests ways the state could create incentives for these previously separate institutions to trade their independence in favor of a more nimble and effective system.

A local CEC would have three essential functions: (1) assembling and disbursing funds for each student’s personal education fund; (2) monitoring the quality, innovativeness, and responsiveness to economic change of the learning options available to students; and (3) protecting students by ensuring valid information for choices among diverse learning experiences, monitoring equity of student placements, and identifying fraudulent or ineffective schools or learning providers.

The essay on funding also discusses students’ personalized education funds, including so-called “backpack funding” that follows students through different learning experiences, and how they can be assembled and managed. The remainder of this essay focuses on the promotive and protective functions of light local governance.

Promoting options, innovation, and responsiveness

Unlike a traditional school board, a CEC would try to represent the community’s future needs rather than its current set of learning providers. A CEC would have a budget amounting to a fixed percentage of the annual amount added to students’ backpacks, with which it would:

—Assess the overall performance of the local education system.

—Ask whether the current mix of options is preparing individual students and the community as a whole for a demanding future (and whether some students are suffering discrimination or some economic needs are being neglected despite good performance on average).

—Determine whether innovations available elsewhere should be imported or copied.

In any city or metro area, the CEC would develop information on the overall health of K–12 education in the locality — rates of student growth relative to similar localities, overall improvements in student graduation and persistence in school, and health of the overall education labor force (e.g., the numbers of teacher applicants per vacancy, net gains or losses of staff to other localities). To do these things a CEC would either form data-sharing agreements with other localities or cooperate with state-level data collection.

CECs will inevitably be pressured to measure and inspect schools in detail as problems and disputes arise. These pressures also threaten to expand the CEC’s costs and thrust it into the roles of regulator and compliance overseer. As CECs gain experience, some might seek greater insight into local instruction providers through surveys and sampling-based studies. Minimizing such intrusions on school autonomy will depend on providers: Will they voluntarily provide valid information about instructional programs, student experiences, and results? Can providers’ honesty be ensured by occasional audits? For advanced thinking on measurement issues in a nimble education system, see iNACOL’s recent report, “Fit for Purpose: Taking the Long View on Systems Change and Policy to Support Competency Education.”

A CEC would also reach out to local businesses and research institutions to identify missed opportunities or emerging needs. CEC members or staff could also meet with representatives of groups and neighborhoods who think the options available do not meet their children’s needs.

The CEC could then seek to recruit schools or learning providers from elsewhere, or gain access to promising online and experiential learning programs. In this respect, the CEC would encourage innovation and assess new possibilities, but it would not own any learning providers and could not mandate their use. Its role would be to call attention to opportunities and create plausible visions of the future, but it could not force anyone to use an idea. A CEC would identify opportunities for students and alert local schools or nonprofit entities to needs and opportunities.

This aspect of the CEC’s role would be highly consequential for its community’s future. If a CEC were too loyal to existing schools or could not attract quality providers and enlist the participation of quality local businesses and cultural institutions, the local economy would likely suffer. As we suggest in “A Democratic Constitution for Public Education,” local government leaders or state officials could require reconstitution of an ineffective CEC.

Protecting students’ opportunities and the public interest

An education system designed to meet the needs of students and entire communities must address a number of tough questions: What person or institution will be responsible for an individual student’s learning? How will results be measured and interpreted? How can measurement be done in ways that inform choices but do not encourage sameness and compliance? What can be done when students don’t learn what they were supposed to learn from a particular source or pathway? These are familiar questions that fit under the label of “accountability” in a conventional, centrally managed school system. We avoid that term here, because in this model schools will be independent of, not subordinate to, government. A governance entity like a CEC could provide information and critique, and in some extreme cases disqualify egregious providers, but it could not perform traditional supervisory functions.

In a nimble, personalized education system, local CECs would have important but limited roles in protecting children’s opportunities and the public interest. Local governance could ensure conditions that allow learning providers to succeed, help families make informed choices, and make life tough for fraudulent providers. But it could not totally eliminate risk for families, students, and quality providers.

Even in the existing public education system, with school boards at least nominally in control and able to issue mandates, questions about student protection and accountability are sharply contested to the point that most states and the federal government have opted to live with risk and ambiguity. Today’s schools and teachers can’t be held fully responsible for all aspects of student learning, but no other entity is responsible at all. Student achievement testing is under attack, but there is no other method for promptly identifying a student who is not learning so problems can be remedied quickly. Schools are encouraged to pay attention to individual needs, but it is not clear what should be done for students who do not learn how to read, analyze, and compute.

Under these circumstances, the adage “we are all accountable” amounts to saying that students will find out when they enter jobs or higher education whether they learned what they needed. Will that also be the case in a more nimble, personalized system? Our answer is, not necessarily. But improving on a situation where students and their families are essentially on their own will require degrees of clarity and candor (that public education has to this point avoided) while addressing four vital areas:

—Making sure all students, including the disadvantaged, attain core gateway knowledge and skills early so they can then pursue more specialized pathways.

—Making sure career pathways are valid (i.e., lead to the kinds of opportunities promised).

—Making sure students develop civic understanding and soft skills.

—Making accountability the subject of learning and continuous improvement. CECs would play limited but vital roles in each of these activities.

Making sure students gain core knowledge and skills

The goals of a nimble system of public education are very ambitious, especially when compared to the current system, where the goals are essentially to minimize the number of students who give up before they are awarded a high school diploma. In a nimble, personalized system, every child must learn the basic skills, understandings, and analytical capacities that are gateways to success in any educational or economic endeavor. They should then have opportunities to develop some select skills and understandings to a high degree so they can make a living in a complex modern economy, and they should be able to upgrade their capacities as needed throughout life.

By gateway skills and understandings we mean those that are indispensable for any course of advanced or specialized learning. These gateway skills and performance minima would need to be found empirically: What do individuals who succeed in school and work know and master that individuals who fail to graduate and find rewarding employment don’t? Examples could include reading for understanding and inference (versus simple decoding), often introduced around age nine; writing and speaking for clear storytelling and persuasion; mastery of fractions, decimals, and rates and the conversions among them; basic algebra; a basic understanding of the meaning of science and verification; and some understanding of core democratic principles. These must be clearly established through research, working backward from results rather than through negotiation among interest groups.

Students must master these skills as early as possible so they have time to develop more specialized employment and citizenship skills and knowledge. That does not mean that instruction must be narrow or standardized. Some families might choose highly structured schools that focus on core skills and prepare all students on an ambitious timeline; others might choose schools that offer many routes to the same goal or mix and match learning opportunities from diverse sources.

Because these choices are so consequential, it is essential that parents have a great deal of information about the performance of different approaches to core gateway skills. This would almost certainly require using tests of specific skills and subject matters. These could be designed to assess only an individual student’s mastery of a particular gateway skill (e.g., the ability to transform fractions to decimals). Tests could be supplemented by evidence of a student’s readiness for more advanced and specialized education and training, and by measuring the number of years it takes a student to master all core skills.

Existing tests for accountability take too much time, happen too often, and cover too many topics too shallowly to assess students’ readiness to enter career pathways. Tests required by state government or CECs should be as demanding as necessary to be predictive of students’ later ability to use the skills, but no more. State governments would have significant data and analytical capacity advantages in identifying the few core gateway skills required to design brief and focused tests for mastery, and CECs might be required to use assessments provided by their states for this purpose.

CECs could oversee testing, analysis, and security of results to prevent tampering by schools and learning providers. CECs could allow students to take core and gateway tests any time they are ready, but would not require any other form of testing that could be linked to a particular student.

Thus, schools educating younger students would not be consumed by annual test prep and could instead offer diverse enrichment programs and experience-based learning programs. CECs could, however, administer school climate and student safety surveys, and assess the veracity of claims made by learning providers on the basis of tests and other measurements.

Beyond assessment of core gateway skills and some measurements of school climates and safety, could CECs leave everything else to parents and learning providers? This possibility raises a very hard question indeed: What would happen if, despite the parent choosing and the provider delivering as promised, a student did not learn core gateway skills before reaching age 14, or for that matter, 18? Would the student and family just be out of luck? Would public funds be available until the student learned the core gateway skills? If that took several more years, would the student then lose out on opportunities for more advanced and specialized learning premised on those skills?

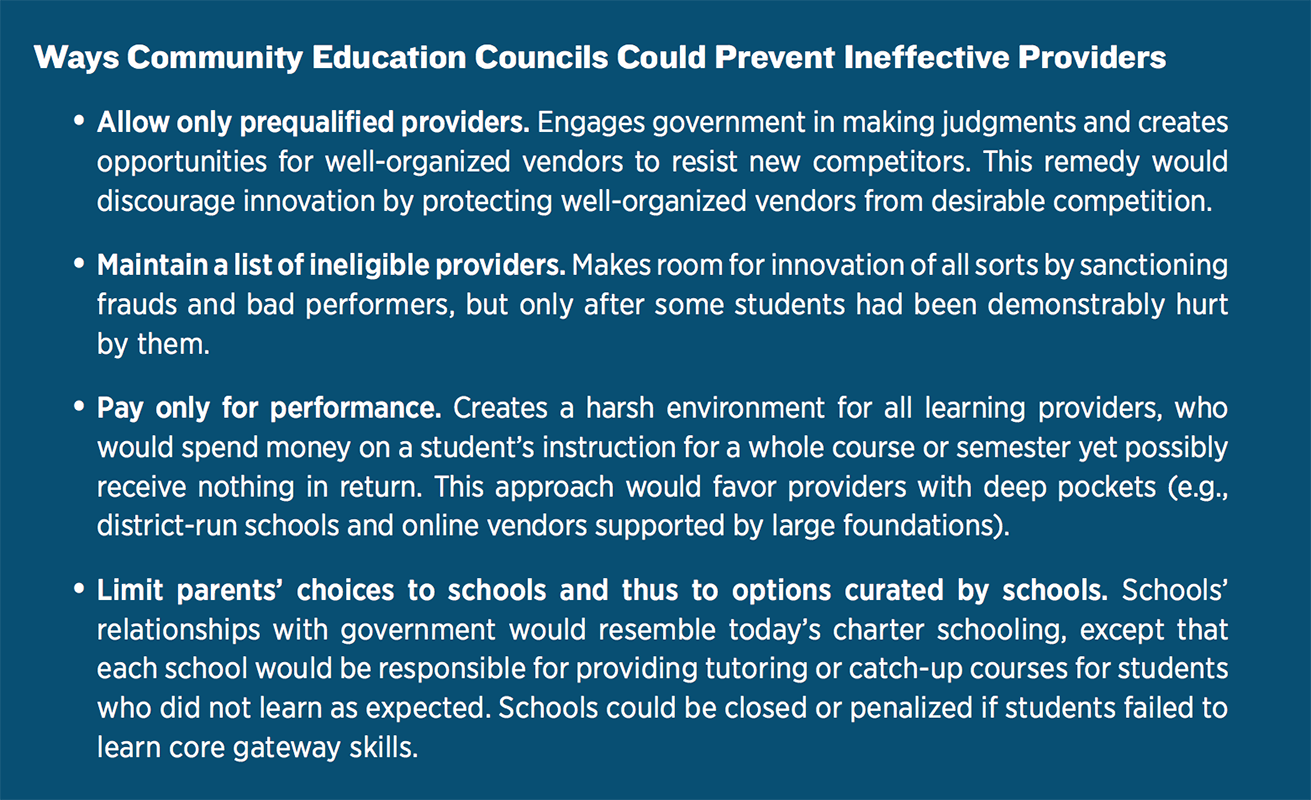

The most important protective action CECs could take would be to help parents avoid ineffective or fraudulent providers. The box below suggests some ways this could be done and assesses each in terms of whether it would put a community on a slippery slope toward allowing only conventional and “proven” providers that prepare students to succeed in the current, not the future, marketplace for skills. Given this risk, if CECs retain the power to disqualify a given provider, they might subject any such actions to review in court or by a panel of university-based researchers.

Different localities might experiment with all of these options. Some will likely follow the more conventional approach of disqualifying ineffective providers. However, some localities might experiment with more information-based approaches. These localities should make arrangements to closely monitor results to guarantee that no student wastes many years with little learning to show for it.

Curating standard and unique pathways

Once students have mastered core gateway skills, a nimble system must support the many different ways students can prepare for higher education, careers, and professions. Without any structure around a particular course, students will not know what sequence of learning experiences is most likely to prepare them for any particular future. The range of options available at any one time can’t be infinite or chaotic, so CECs might have the authority to limit the number of new learning providers who enter the locality in any year, and to disqualify or at least negatively review ineffective ones.

Pathways could be organized by schools, higher education institutions, regional governments and compacts, industries, professions, or combinations thereof. Some might have little difference from current academic pathways into liberal arts, law, and business. But others might be much more explicitly organized around preparation for computer science, health professions, social service delivery, advanced manufacturing, or food growing and production, as well as for careers or industries especially relevant to particular localities.

Students would probably enter into pathways between ages 12 and 14—as soon as they master core gateway skills. Though a small proportion of students might want to concentrate on a very narrow skill set, most should be urged to keep their options open and pursue several skill sets.

The specialized pathways would all have consequences for admission to continuing education and training programs. Universities, colleges, and vocational schools can specify what exams students must pass and at what level of proficiency. Students aspiring to universities and professions could not pad their résumés by taking exams in less demanding subjects.

Metropolitan areas, states, or interstate compacts could construct comprehensive systems of pathways, related exams, and methods for tracking graduates. As in England, many U.S. students might choose to attend traditional schools and follow pathways curated or managed by those schools. Familiar accountability arrangements would apply: student results affect the future choices parents make, and if student results are consistently bad, government can also intervene (e.g., closure, required improvements).

CECs would provide information on the pathways available, as well as students’ completion rates and employment experiences. But student protection will be much more complex and indefinite when no single entity can be held responsible for pathways that include multiple independent learning experiences and diverse providers. Moreover, when some providers donate services (e.g., mentorship or job shadowing in business; internships with cultural institutions, legislatures, or nonprofits), informed parent choice will be the most important accountability mechanism.

Other essays in this series call for “navigators” — personal advisors who help students sort among possible options and choose pathways and learning experiences that advance their goals and have good track records of performance. Without such arrangements, student protection would depend heavily on provider goodwill and commitment to students.

Key officials, such as mayors and heads of chambers of commerce or regional economic development coalitions, might also influence the actions of entities whose promised contributions to key pathways are not working well for students.

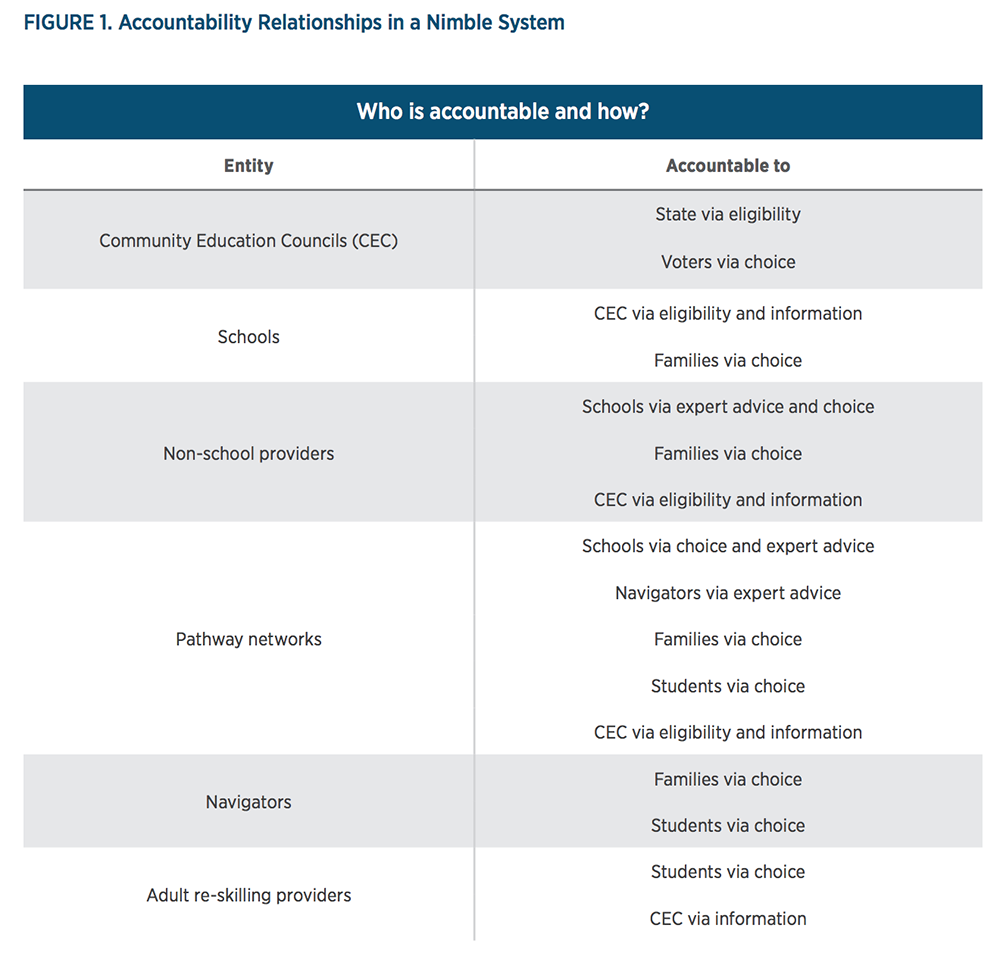

Figure 1 organizes the ways in which, under the concept presented here, the interests of students and the public can be protected. In a future where government is not the dominant provider of instruction and diversity of experience and student growth rates are expected, accountability can’t be a simple principal-agent relationship between government and schools. Schools, pathways, providers of specific instructional experiences — and even CECs — will be accountable in multiple ways and to multiple parties. But, except in a few situations where states or CECs can deny a negligent or low-performing entity access to public funds, most actors in the system are held accountable via a web of information, reputation, and family or student choice.

Improving students’ understanding of economic, social, and civic relationships

Students must learn how to understand the importance of steady effort, work productively with others, own responsibility for results, respect differences, know how to persuade — rather than insult — those who disagree with them, and know when to stick up for themselves and seek help when abused. These understandings in turn depend on what Linda Nilson has called “self-regulated learning,” awareness of one’s own thinking processes, biases, and strengths and weaknesses.

Nilson and others have shown how teachers can help students become self-aware. However, with respect to tolerance, effectiveness in group settings, respect for people of color and other ethnicities, and belief in the democratic process, links to instruction are elusive. It is far easier to identify groups that are high or low in these attributes than to link results to school coursework. Studies that do link educational experience, civic skills, and tolerance typically point to global attributes of schools (e.g., shared values, commitment to exploration of multiple sides of an issue) rather than to specific coursework.

Today, Americans put high priority on outcomes that no one knows for sure how to produce at scale. It is not clear how much education for adult skills can remain the responsibility of schools, or how much choice parents should have in these matters. Civics and transactional skills are subjects of a great deal of thinking and innovation, with new experience-based school curricula (e.g., Knowledge in Action AP courses in government and politics) and many options for well-designed direct experiences of debate, negotiation, and facing consequences (e.g., debate teams, mock courts, model UN, city simulations), most of which are available from organizations other than the public school system.

At this point it is not clear which course or experience has the greatest short- and long-term effects on civics or related skills, or how best to match students with learning experiences. Nor is it obvious that anything can replace a real educational home base in a particular school or advisory group. This is clearly an area in need of disciplined research, development, demonstration, and testing, which could be possible in a nimble system that requires education about problem-solving, collaboration, and civic values but encourages personalization. Without greater clarity about what works, it is likely that this vital objective of public education will remain an aspiration, not something for which schools or vendors can be held accountable.

CECs should encourage experimentation and track results, both in terms of students’ attitudes and their civic participation. In the long run, it might be possible for CECs to help families choose among schools and learning providers on the basis of adult skills outcomes. However, despite the importance of these skills, any premature mandates about method or student testing would be counterproductive.

We need experiments and learning about the protective function

Until now, what’s called accountability in public education has focused primarily on government: the tests it will mandate and other information on teachers and students it will keep, how it will determine whether a given school is dangerously ineffective, and what it will do for students who do not learn in the schools provided.

Government has not found a valid or politically sustainable approach to accountability. Instead, the tests by which government assesses schools have come under attack, as have potential remedies linked to student scores (e.g., consequences for individual teachers and school reconstitution, closure, replacement with charter schools). As a result, government hesitates to act even when it has clear evidence that particular schools are not serving students well, and many schools of choice continue operating even when the most knowledgeable parents avoid them.

Can the new approach to governance sketched here ensure that parents always know what they are choosing, and that communities know whether they are developing the workforce needed for the future? To what extent can government protect children from bad choices made by their parents without chilling innovation? Who is responsible to find corrective action if students, whether in small or large numbers, don’t learn the core gateway skills and are therefore unprepared for any pathway? How do pathway organizers ensure discipline in the work of paid and unpaid providers? What happens if some pathways prove to be dead ends for students and others become oversubscribed so that opportunities must be rationed?

These questions can’t be answered a priori. They must be answered in real time as states and localities press for greater personalization and responsiveness to economic change. A nimble system must be open to experimentation and tolerate some failure, but it ultimately can’t leave results, on which the welfare of children and communities depend, to chance.

Paul Hill’s research focuses on reform of public elementary and secondary education. A former federal policy adviser on education, he founded the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)