Analysis: Study of 6 ‘Grow Your Own’ Teacher Prep Programs Shows How They Can Improve the Diversity of the Workforce

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

America’s teaching workforce is overwhelmingly white. But as pandemic stresses add up and a tight labor market offers other options, it’s Black and Hispanic educators who are substantially more likely to say they plan to leave the profession, threatening to exacerbate this lack of diversity.

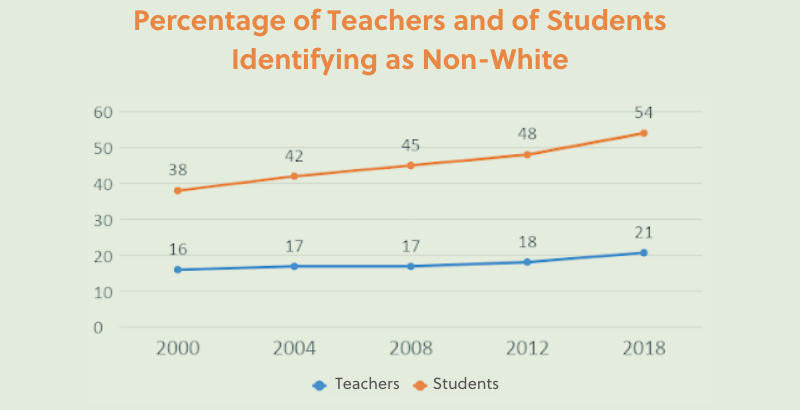

The mismatch between a homogenous pool of teachers and an increasingly diverse student body has only gotten worse over time. In the 1999-2000 school year, 38 percent of public school students identified as people of color, compared with just 16 percent of teachers. In 2017-18, more than half of students were people of color, but the share of teachers of color remained stubbornly low, at 21 percent. This is a troubling trend, particularly since students of color benefit from having access to teachers who look like them. Their test scores, graduation rates and college-going all improve with no adverse effects on white students.

And yet, people of color aren’t being recruited into teaching — at least, not at the pace needed. But our research shows that local, “grow your own” alternative teacher preparation programs can help to strengthen the diversity of the teaching workforce, as well as enable districts to address broader staffing challenges.

We studied six alternative teacher preparation programs in U.S. urban school districts that serve substantial numbers of low-income students and students of color. (The specific districts were kept anonymous in our report to ensure the confidentiality of research participants.) The programs were designed and administered by the organization TNTP in partnership with the local districts.

In every case, these programs recruited more people of color into teaching than the districts’ other recruitment efforts typically did. On average, across all the programs, the TNTP recruits were 52 percent people of color, compared with 43 percent for other new teachers. In one program in Massachusetts that was particularly successful, 44 percent of the TNTP recruits were individuals of color, compared with just 21 percent for the district’s other new teachers.

Overall, the TNTP effort added 74 more teachers of color than might otherwise have been hired just in those six districts. Teachers recruited by the TNTP programs were also at least as effective — and in some cases more so — at raising student achievement as other new teachers.

Each of these programs set out to enhance the racial, and in some cases gender, diversity of the recruitment pool. They were most effective when they accomplished three things:

Lowering costs for teacher trainees. This residency-style pathway into teaching included a summer training program, after which candidates entered classrooms as paid teachers while receiving coaching and in-person training. Tuition paid to the TNTP programs was significantly lower than is typical for a university degree program, and some trainees received stipends for their summer work as well. Across every program that we studied, aspiring teachers of color described how reducing costs in both time and money were essential to their decisions to enter the profession.

Recruiting from the community. School staff in non-teaching roles, such as teachers’ aides, are more than twice as diverse (around 39 percent non-white nationally) as teachers. The programs reported that recruiting individuals already working in schools was critical to their success. Another successful strategy was stepping up outreach to nearby minority communities, often partnering with community and nonprofit organizations or creating targeted marketing campaigns.

Help with licensing. The tests to get a teaching license are known to disproportionately screen out minorities, even as they are imprecise predictors of teacher quality. To work around this barrier, one TNTP program set earlier application deadlines and provided accepted candidates with intensive test preparation, bolstering their chances of passing even before the start of the summer training program. Another program took advantage of state rules that allowed principals to request waivers of test requirements on a case-by-case basis. That gave promising candidates who had not yet passed the tests more opportunities to do so during their first year in the classroom.

Our research findings illustrate that there are effective ways around the hurdles that have been keeping otherwise interested people of color from becoming teachers. “Grow your own” programs can widen the pathway into the teaching profession to help ensure that the teaching workforce better reflects the diversity of the students it serves.

Benjamin Master is a policy researcher at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation who focuses on human capital development and management in K-12 schools. Christopher Doss is a quantitative researcher at RAND who specializes in fielding causal and descriptive studies in education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)