Analysis: Student Enrollment Drops, But School Labor Costs Continue to Rise. Is ‘Per-Pupil Spending’ Really an Accurate Description?

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears most Wednesdays; see the full archive.

We have heard a lot about educator shortages recently, but over the past few weeks the media have sounded the alarm over a different shortage: students.

The Associated Press, Washington Post, Chalkbeat, Politico and The 74 are national outlets that highlighted steep declines in K-12 public school student enrollment and the dangers of layoffs and deep budget cuts when federal relief money is gone.

Chicago, Minneapolis and Sacramento — all cities with recent teacher strikes — proposed cuts to find money to pay labor costs amid declining enrollment.

This attention is leading us into a welcome debate about how schools are funded and whether “per-pupil spending” is really an accurate description of how revenues are allocated. While we ostensibly fund public schools according to the number of students they enroll, history shows that in most places, changes in the size of the student body bear little relationship to the amount of money added or subtracted.

I used to extract enrollment, staffing and finance figures for every K-12 school district every year from U.S. Census Bureau data. I would compare them to corresponding figures from five years earlier. Here’s a link to the last time I did it, which showed that from 2005 to 2010, enrollment grew by 0.3%, the number of teachers grew by 3.8% and per-pupil spending grew by 22%.

The responses of individual states and districts to enrollment gains and losses were all over the map. In many places, enrollment and spending seemed completely disconnected.

Nevertheless, if we accept that fewer students will lead to less funding, we still should have been well prepared for the current situation.

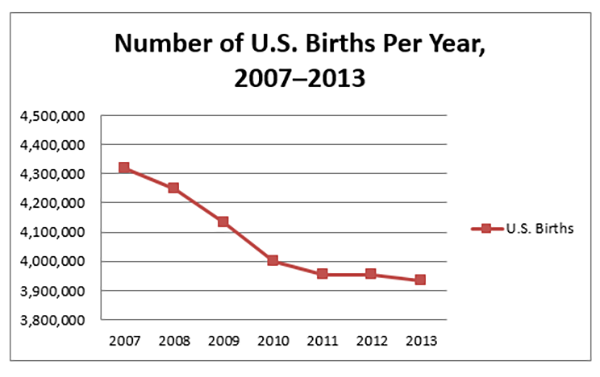

In April 2015, I headlined a blog post “The Coming Student Shortage,” based on this graphic from a Fordham Institute column:

With the number of births down dramatically by 2013, it stood to reason that kindergarten enrollment would be lower in 2018, and it was. By 2018, there was even more warning.

“U.S. Births Dip To 30-Year Low; Fertility Rate Sinks Further Below Replacement Level” read a headline about a report from the National Center for Health Statistics. It prompted me to write at the time, “A low birth rate has all sorts of implications for the nation, but the effect on public schools is obvious. Fewer births means reduced enrollment. If we were smart, we would start planning immediately for that eventuality.”

I had several ideas, but I already knew it was wasted effort. “As long as the economy rolls along and tax revenues increase, school districts will hire more teachers and support workers, even with shrinking enrollment,” I wrote. “And since the available workforce is also shrinking, this will lead to — you guessed it! — manufactured panic about teacher shortages.”

Last week, the National Education Association released several reports with “alarming new data about educator pay and other key findings related to what is contributing to the nationwide educator shortage.”

Those reports showed that from 2020 to 2021, the nation was forced to get by with 1,881 fewer teachers (down 0.06%). There were, however, 1,328,387 fewer students to teach (down 2.65%). We lost one teacher for every 735 students who disappeared.

Where did those students go? We have seen a lot of different answers: charters, homeschooling, private schools, virtual schools, etc. Only one commentator that I have seen painted a darker picture.

“Where are they? They’re not going to private school. They’re not going to any other school. They are at home or not in school at all,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators.

This is the most worrisome interpretation, and the least discussed. Compulsory school attendance has been on the books in every state for more than 100 years. The COVID crisis marked the first time that it was largely unenforced. Most states went for 18 months without any clear idea of where some children were during the school day. Is it unreasonable to assume that when schools reopened, at least some of those students had already absorbed the message that showing up wasn’t that important?

The American K-12 system can either be the source of education for all students or the world’s largest government jobs program for adults. Time to choose.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)