Analysis: States To ‘Likely See a Doubling’ of Pre-Pandemic Chronic Absenteeism

Based on early data from four states, experts suggest recently released federal data is an “undercount”

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It’s not unusual for federal education data to be a school year or two behind. But it doesn’t often come with a red warning label urging “abundant caution.”

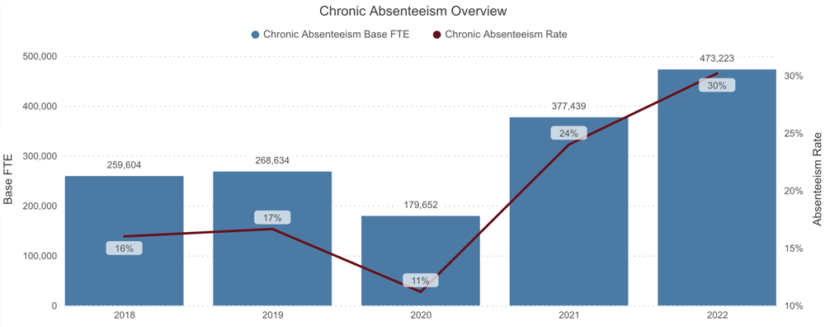

That’s how the U.S. Department of Education released chronic absenteeism data last month for the 2020-21 school year. But more recent data, available from just four states, suggests the government’s figures seriously “undercount” the problem’s scope.

If the rest of the country saw rates as high as those in California, Connecticut, Ohio and Virginia, that would mean over 16 million students missed large chunks of the 2021-22 school year.

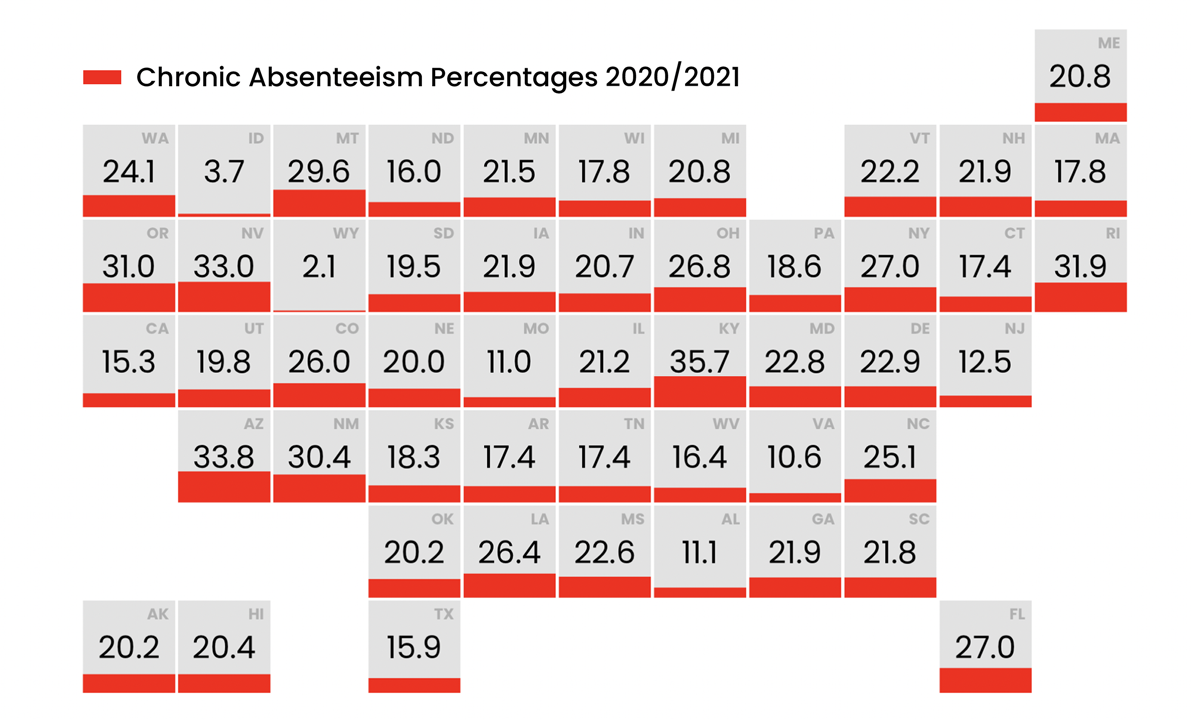

Compared to pre-pandemic rates in 2018-19, “we will likely see a doubling in chronic absence,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of the nonprofit Attendance Works, which teamed with researchers at Johns Hopkins University to analyze the federal data. Those numbers showed that 10.1 million students missed at least 10% of the 2020-21 school year.

Data Analysis

Chronic Absenteeism Rates:

Before and During Pandemic

One reason Chang suspects the federal count to be too low is because of the leap in chronic absenteeism in those four states. For example, the federal count shows 15.3% of California students were chronically absent in 2020-21. But according to School Innovation and Achievement, a company that works with districts to improve attendance, 27.4% of students were in the chronic to severe range last year — a time when schools were mostly open.

‘Highly dubious’

Attendance Works partnered with the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins to compile statewide chronic absence data available on the Education Department’s ED Data Express website. But they call some of what they found “highly dubious.”

The attendance data is flawed, Chang explained, because of the inconsistent ways states and districts calculated attendance during remote learning. Some students were marked present if they just logged into Zoom and left. This year, she added, states and districts not only face the challenge of improving the way they track the data and release it to the public, but also reengaging students who missed large portions of last school year.

The data shows, for example, that only 3.7% of Idaho students were chronically absent in the 2020-21 school year, but districts in the state, such as Coeur d’Alene and Boise, are reporting rates in the 10% to 15% range.

In five states, chronic absenteeism rates actually went down. That’s unlikely, Chang said.

At the other end of the spectrum, rates in Arizona, Kentucky, Nevada and New Mexico were at least 30%. But that could still be far from accurate. Districts such as the Albuquerque Public Schools saw rates as high as 43% last school year.

Marguerite Roza and Chad Aldeman of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab drew attention to the lack of accurate education in a recent op-ed saying public schools have “missed the data revolution.”

“Good luck getting real-time data on how many children are enrolled in public schools, are chronically absent, or are making academic progress as a result of federally funded relief efforts,” they wrote. “We don’t have it on a national level. States don’t have it. Neither do most districts.”

In New Mexico, officials say just because most schools are no longer engaged in remote learning doesn’t mean the need to clearly define attendance for students learning virtually and collect accurate data is gone.

Some families still choose virtual when it’s available, and some schools use online learning for teacher training or emergencies, like a gas leak. Officials are currently drafting new guidelines to help districts count attendance for students learning at home and those planning to finish by January.

“We’re working on guardrails,” said Gregory Frostad, the director of policy and legislative affairs for the New Mexico Public Education Department, “There can be good reasons [for remote learning]. We don’t have to just say that learning can’t continue.”

‘One of the best indicators’

Skyrocketing absenteeism, meanwhile, is helping Robert Balfanz, who leads the Johns Hopkins center, target efforts to match students with tutors and mentors as part of a new national effort announced in July. The National Partnership for Student Success, housed in the center, is fielding requests for assistance from districts, nonprofits and government agencies.

Chronic absenteeism is “one of the best indicators of which schools are likely in need of additional … supports,” Balfanz said. “It signals both a high likelihood of interrupted instruction and disconnection from school.”

The partnership’s website offers a new feature where potential tutors and mentors can search for opportunities to serve in their community.

Chang said her organization has also been hit with a “deluge” of requests for expertise on tracking data. She’s encouraged that district leaders have boosted training for school staff instead of “just throwing up their arms and saying ‘Oh no.’ ”

Districts and other community agencies have launched an array of efforts to improve attendance. In Albuquerque, teams of educators — including social workers, administrators, nurses and teachers — are delving into the reasons students aren’t showing up.

And in California’s Merced County, the district attorney’s office started classes for parents whose children have missed so much school that they’re at risk of being referred to the juvenile justice system.

“We try not to treat them like they’re in trouble,” said Monica Adrian, a behavior support specialist with the Merced County Office of Education. “We look at … some of the stressors that might lead to chronic absenteeism. There’s always another side of the story.”

But Chang said there was still so much disruption last school year — with quarantines and high staff vacancies — that it was hard to determine if those strategies made an impact.

“I think we’ll know better this year whether people are able to engage students [when it’s] a little less crazy,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)