Analysis: No ‘Gold Standard’ in Ed Tech; Continuum of Evidence Needed to Ensure Technology Helps Students

This is the third in a series of essays surrounding the EdTech Efficacy Research Symposium, a gathering of 275 researchers, teachers, entrepreneurs, professors, administrators, and philanthropists to discuss the role efficacy research should play in guiding the development and implementation of education technologies. This series was produced in partnership with Pearson, a co-sponsor of the symposium co-hosted by the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education, Digital Promise, and the Jefferson Education Accelerator. Click through to read the first and second pieces.

A general consensus was evident during discussions at the recent Ed Tech Efficacy Research Symposium. Educators, researchers, funders, and companies all agreed: We need a robust continuum of evidence.

“Do not kill a mosquito with a cannon.” —Confucius

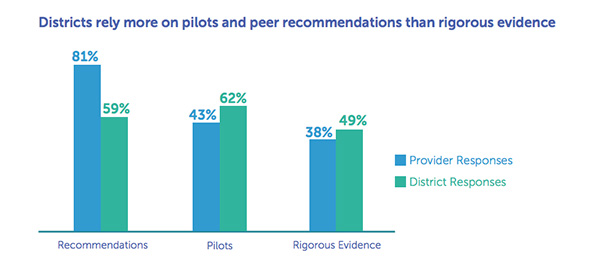

Different types of evidence are needed at different levels of district implementation and stages of ed tech product development. Research has shown that districts tend to rely primarily or even exclusively on peer recommendations and pilots, rather than rigorous evidence, to decide what ed tech to purchase (see Figure 1). However, when it comes to evidence, the same level of rigor may not be necessary for all ed tech decisions.

http://digitalpromise.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Improving_Ed-Tech_Purchasing.pdf

Useful research begins with proper design. Academic research often consists of traditional large-scale approaches and randomized control trials that seek to demonstrate causal connections that can be extrapolated. But oftentimes large-scale research designs are inappropriate for informing more rapid, practical decisions.

School leaders are often making smaller-scale decisions, such as whether to allow teachers to use an educational app to enhance the standard curriculum. For these types of decisions, most school leaders don’t require absolute certainty that an app is the key factor for improving student achievement. Instead, they want to know the extent to which teachers and students adopt the technology (e.g., information on usage) and whether an app has the potential to improve outcomes for their students and their teachers. Other types of research, such as rapid cycle evaluations (RCEs), can help school and district leaders produce the evidence they need to inform their decisions on a reasonable timeline and at a reduced cost.

Smaller, more nimble research approaches can also inform other questions educators and school leaders face around context and scope. Often, they want to know which tools work in specific circumstances. If, for example, educators are examining a tool specifically to use in an after-school program, research that offers overall general outcomes might not be the most useful. A targeted RCE could assess whether a tool is accomplishing its intended objectives in this setting and for the specific sample. Evidence collected through smaller studies in local contexts may not enable generalizability, but the collection of some evidence is better than no evidence and is certainly better than a reliance on biased marketing material or the subjective opinions of a small group of peers.

Additionally, traditional research often results in a binary estimate: Either the treatment worked or it didn’t. But learning technologies aren’t static interventions, and contexts differ immensely. Products are built iteratively; over time, functionality is added or modified. A research approach that studies a product should also cycle with the design iterations of the product and demonstrate the extent to which it is changing and improving over time. Further, snapshot data often fail to fully capture the developmental context of a product’s implementation.

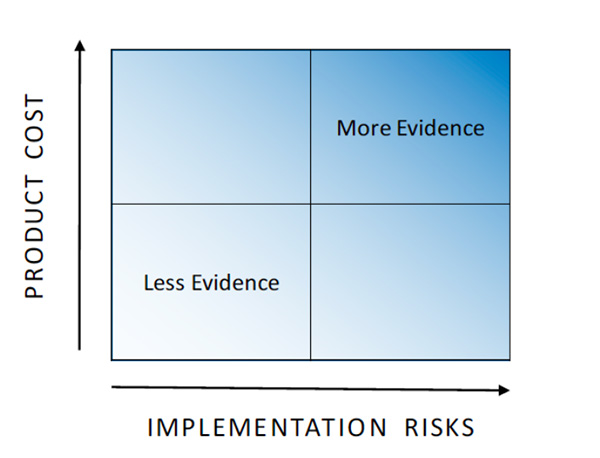

It would be wise for educators to consider the scale, cost, and implications of any given decision when determining the type of evidence that is appropriate for informing it. A continuum of evidence, based on factors like product cost and implementation risks, captures the range of ed tech product research possibilities (see Figure 2). For example, testimonials from several teachers who have used a product in a similar setting may be enough for a teacher to try an app in her classroom. But if a district wants to implement a reading program across all of its elementary schools, stronger forms of evidence should be collected and reviewed before making such a resource-intensive purchase.

Several organizations have created resources to help educators evaluate different kinds of evidence: This guide by Mathematica helps educators identify and evaluate a range of evidence, as does Digital Promise’s Evaluating the Results tool. Lea(R)n’s Framework for Rapid EdTech Evaluation similarly highlights the hierarchy of rigor in different research approaches.

Tools such as the Ed Tech Rapid Cycle Evaluation Coach, LearnPlatform, Edustar, the Ed-Tech Pilot Framework, and the Learning Assembly Toolkit can provide useful support in conducting evaluations of the use of technology. For language to support these variations in ed tech research approaches, the Learning Assembly has created an Evaluation Taxonomy to classify different types of studies and evidence.

Products should neither be developed nor be purchased simply because of a “cool idea.” Rather, companies should use learning science to create products, user research, and implementation science to refine them, and evaluation research to provide evidence of how well they work in different contexts.

The level of evidence companies should be expected to produce should be related to their stage of development.

Development Stage: All companies should be able to explain how learning science undergirds their products as they are initially being developed. For example, early-stage reading products should be designed using the latest research on how young students learn, and professional development services should be grounded in science on how adults learn. Even productivity tools should have a foundation based on human behavior science or systematic evidence from other fields. Collaborating with researchers is often the ideal approach companies take to collecting evidence that their products will be effective. To make this easier, the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education and Jefferson Education Accelerator are creating a database to help educators and companies connect to researchers more easily: the National Education Researcher Database (NERD).

Early Stage: Early-stage companies should conduct user research that captures feedback that enables them to improve their products and services. This research can take many forms, including interviews, surveys, observations, and focus groups. Additionally, data analytics on a user’s interaction (e.g., clicks, activities, or scores) can inform early-stage development, as well as pilot studies, A/B testing, and RCEs. Companies should consider gathering feedback from multiple user groups and multiple settings to understand a representative range of contexts in which they have the opportunity to be effective. Implementation science and design-based implementation research should also be conducted to help stakeholders understand what actually makes educational interventions effective.

Later Stage: At this stage, it’s incumbent on them to participate in evaluation research that provides evidence of how well they work in different settings. Ideally, this research includes a sufficiently representative comparison group — that is, a group of students not using the product who are similar to the students who are using the product.

The demand for evidence is increasing. When the U.S. Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2016, it strengthened the focus on using evidence to make purchasing and implementation decisions. To help educators and other stakeholders, the U.S. Department of Education released non-regulatory guidance on Using Evidence to Strengthen Education Investments that highlights a focus on identifying local needs, engaging stakeholders, and promoting continuous improvement. This guidance also includes definitions of “evidence-based” included in ESSA and includes recommendations on how to identify the level of evidence for various interventions.

Essentially, ESSA outlines four tiers of evidence: 1) strong, 2) moderate, 3) promising and 4) demonstrates a rationale. In an ideal world, all education technology would have strong evidence to support its use. Practically, most products will not reach that level because of the cost and complexity of performing research to that standard. All products used in schools, however, should at least be able to demonstrate a rationale, which means that some efforts have begun to study the effects of the product and that there is a well-defined logic model informed by research. The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University School of Education recently launched a site to help educators identify programs that meet ESSA standards.

In conclusion, traditional views on research rigor and scientific evidence have limited the extent to which research informs practice, and vice versa. Rather than taking on a narrow view that the “gold standard” randomized control trial is the only research design that produces acceptable evidence, the field needs to understand that there exists a continuum of evidence, and that different types of evidence inform different types of decisions. Approaching product development, adoption, and evaluation through this lens would foster healthy collaborations and relationships among educators, researchers, administrators, and other stakeholders in the education ecosystem, as well as ensure the ultimate goal of all of this: that students can and will learn better.

Authors:

Dr. Christina Luke, Project Director — Marketplace Research, Digital Promise

Dr. Joshua Marland, Director of Data & Analytics, Highlander Institute

Dr. Alexandra Resch, Associate Director, Mathematica Policy Research

Dr. Daniel Stanhope, Senior Research Officer, Lea(R)n

Katrina Stevens, Education Consultant & Former Deputy Director of the Office of Educational Technology, U.S. Department of Education

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)