One co-author of the report, “A Coming Crisis in Teaching? Teacher Supply, Demand, and Shortages in the U.S.,” is Linda Darling-Hammond, the founder of LPI and one of the nation’s leading experts on education policy. She was said to be on the short list for education secretary under President Obama, and she may well be again if Hillary Clinton is elected president in November.

Darling-Hammond has had a long and distinguished career in the education policy sector — dating back at least to her stint as a researcher for the Rand Corporation in the 1980s.

In 1984 she wrote a report for Rand titled, coincidentally enough, “The Coming Crisis in Teaching,” which also sought to warn of an impending teacher shortage. Let’s compare that warning with the new one:

1984: “Unless major changes are made in the structure of the teaching profession, so that teaching becomes an attractive career alternative for talented individuals, we will in a very few years face widespread shortages of qualified teachers.”

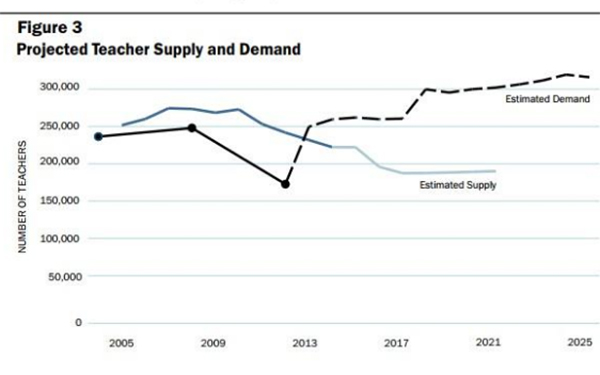

2016: “Unless major changes in teacher supply or a reduction in demand for additional teachers occur over the coming years, annual teacher shortages could increase to as much as 112,000 teachers by 2018, and remain close to that level thereafter.”

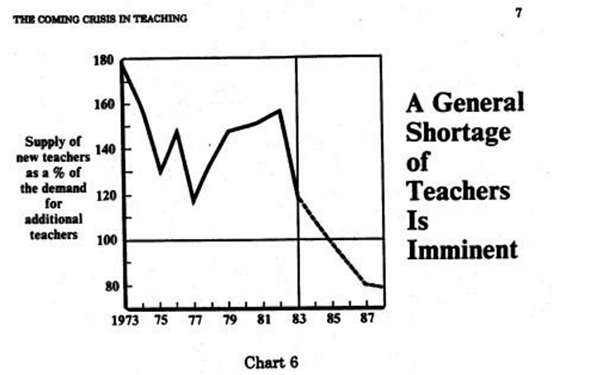

Similar charts depicted when the crossing of the teacher supply and demand lines would occur. First, the 1984 chart:

Then the 2016 chart:

The 1984 report explained that high teacher attrition due to poor working conditions was a main cause of the shortage. Teachers were leaving the profession because of low pay, dissatisfaction with working conditions, lack of input and the prevalence of standardized testing.

The teacher shortage would grow, the report said, until “we will be forced to hire the least academically able students to fill these vacancies, and they will become the tenured teaching force for the next two generations of American school children.”

What actually happened?

A review of the archives of the National Center for Education Statistics shows that the K-12 public school teacher force grew from 2,168,000 in 1984 to 2,401,000 in 1990. That means that all the outgoing teachers were replaced, and an additional 233,000 were hired. Were these new hires necessary because of increased enrollment? No — the pupil-teacher ratio declined over the same period, from 18.1 to 17.0.

The teacher population continued to grow; today, even after a severe recession, U.S. public schools employ almost 3.2 million K-12 classroom teachers, according to National Education Association estimates.

How did we sidestep the first “coming crisis in teaching”? If we believe Darling-Hammond’s 1984 prescriptions, we must have done away with low teacher pay, dissatisfaction with working conditions, lack of input and/or standardized testing. Or, we have hired the “least academically able” for the past 32 years.

Since there is plenty of evidence to show that neither of these is true, it must have been something else. Darling-Hammond may have inadvertently provided the answer in her 2016 report:

In other words, the shortage is not due to a gap between supply and demand, but between supply and “ideal demand,” which she defines as at least a return to pre-recession conditions.

The problem, of course, is that we don’t live in an ideal world. Ideal demand for teachers could be one teacher — or more — for each student. Under normal conditions in a democratic society, that ideal demand can never be met. Would that constitute a teacher shortage of 50 million?

The size of the teacher labor force is not just an economic or an educational issue. It is a political issue, as opposing forces line up to determine where limited tax dollars will be spent. History suggests that teacher hiring usually comes out on top in that calculus, and we should expect it will do so in the future. We should also expect warnings of imminent teacher shortages somewhere around the year 2048.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)