Analysis: New Research Confirms that Charter Schools Drive Academic Gains for Their Own Students — and for Kids in Nearby District Schools

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Thirty years ago, when the charter school movement was just getting off the ground, devotees of big-city school systems worried that these new options would drain critical funding, hurt the kids who were left behind and make a system in which race played a central but often unacknowledged role even more unjust. Yet, in recent years, it has become increasingly clear that concerns about charter-inflicted damage are misplaced — as demonstrated by a pair of new studies that find broad and statistically significant gains for all publicly enrolled students as charter schools expand.

If you’re familiar with the research on charter schools, these results shouldn’t be surprising. After all, for the better part of a decade, a steady stream of studies have found that enrolling in urban charters boosts the academic achievement of low-income Black and/or Hispanic students. For example, a 2015 CREDO analysis found that Black students in poverty gained almost nine weeks of learning in English and almost 12 weeks in math per year by attending an urban charter school instead of a traditional public school.

Other research has found that charter schools’ effects on the achievement of students in neighboring district schools are neutral to positive. For example, a recent review of the literature on this question identified nine studies that found positive effects, three that found negative effects and 10 that found no effects whatsoever.

Put those two findings together — that urban charters boost the achievement of their own students and that they have a neutral to positive impact on the achievement of children in traditional public schools — and the logical implication is clear: The growth of charter schools should boost achievement overall for students in a given community.

Yet, for complicated reasons related to data collection and accessibility, direct evidence is limited to a handful of studies. The first, a 2019 Fordham Institute report titled Rising Tide: Charter School Market Share and Student Achievement found a positive relationship between the percentage of Black and Hispanic students who enrolled in a charter school at the district level and the average achievement of students in these groups — at least in the largest urban districts. The second, by Tulane University’s Douglas N. Harris and Feng Chen, found a positive relationship between the percentage of all students who enrolled in charter schools and the average achievement of all publicly enrolled students, especially in math.

Now, both of those studies — which include more than nine out of 10 American school districts and nearly 20 years of data on charter school enrollment — have been updated with additional years of data and estimates, and their findings are beginning to converge.

First, both studies find that charter schools’ overall effects are overwhelmingly positive. For example, according to the Tulane study, moving from zero to greater than 10 percent charter school enrollment share boosts the average school district’s high school graduation rate by at least 3 percentage points. Meanwhile, the Fordham study suggests that a move from zero to 10 percent charter school enrollment share boosts math achievement for all publicly enrolled students by at least a tenth of a grade level.

Second, both studies find that the growth of charter schools leads to bigger and more consistent benefits in math than reading. For example, according to the Tulane study, moving from zero to greater than 10 percent charter school enrollment share leads to a 6 percentile increase in math scores and a 3 percentile increase in reading scores.

Third, both studies find that achievement gains are concentrated in major urban areas, consistent with much prior research on charter school performance. For example, according to the Tulane study, moving from zero to greater than 10 percent charter enrollment share in the average school district is associated with a 0.13 standard deviation increase in math achievement. But in metropolitan areas, this change is associated with a 0.21 standard deviation increase in match scores.

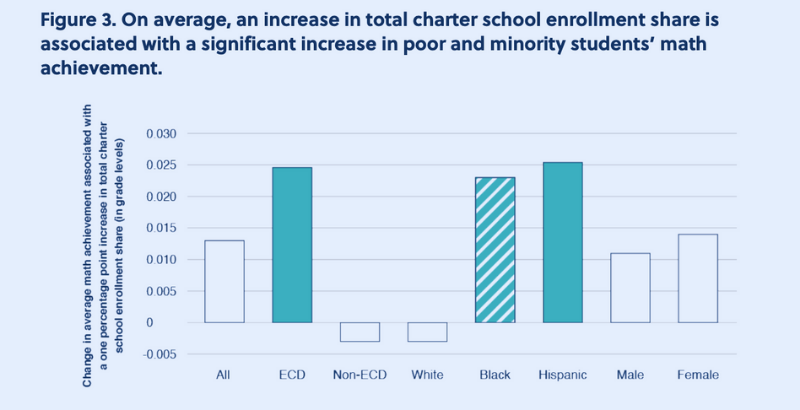

Finally, both studies find that poor, Black and Hispanic students see big gains. For example, according to the Fordham study, a move from zero to 10 percent charter school enrollment share boosts math achievement for these children by about 0.25 grade levels. Poor students also see a 0.15 grade level increase in reading achievement.

These findings are incredibly important, given longstanding concerns that the growth of charter schools would hurt kids in traditional public schools, and given the opposition that charter schools still encounter in some places. To fulfill their potential, charter schools must be allowed to grow. But for that to happen, policymakers and the public need to understand what the best research about charters actually says.

At a time when the whole country seems to be in a foul mood, here’s some good news: As charter schools grow and replicate, parents gain access to high-quality schools that better meet their children’s needs, students who remain in traditional public schools see better outcomes, and racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps that have resisted many other well-intentioned reforms begin to close.

In short, nobody needs to take sides on this issue — because it truly is a win-win.

Michael J. Petrilli is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. David Griffith is associate director of research and author of the Rising Tide and Still Rising studies.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)