Analysis: Mapping Students’ Support Networks Is Key to Supporting Their Remote Learning Success. How Schools Can Make That Happen

Despite educators’ valiant efforts this past spring, too many students still struggled to connect to their peers, teachers and counselors. Some went missing from virtual classes altogether, leaving teachers and principals scrambling to find them. Others, particularly middle and high school students, reported a troubling lack of people to turn to for academic and emotional help. These levels of disconnection threaten both students’ well-being and their academic progress.

Surrounding students with an interconnected web of positive relationships is the foundation of healthy youth development. And within that web, access to what researchers dub a “person on the ground” — a mentor, tutor, parent or neighbor who is physically present to offer support — is a proven, critical ingredient to successful distance learning.

What will happen come fall? District administrators and principals are in the thick of contingency planning for a year of unknowns. With nearly 75 percent of superintendents preparing for some form of distance learning, ensuring that students have a well-connected support network from school and at home could prove the linchpin of success.

Weaving those webs will require identifying the individuals in students’ networks. Emergency contact and caregiver information that school districts typically collect may not suffice. And relying solely on teachers of record may not tell the whole story of whom students feel comfortable turning to for help. Instead, schools would be wise to gather reliable information on the broader stock of relationships students possess at home, in their communities and at school.

A relatively simple approach could help: relationship mapping, a method that schools have used in the past to measure and improve upon their culture and climate. One popular tool, the “Relationship Mapping Strategy” created by the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Making Caring Common Project, enables educators to plot strong connections between students and adults in school. To gather data, school administrators list the names of each student, by grade level, and then prompt teachers and staff to place an X next to the names of students who they believe would approach them if they had a personal problem, and another next to the names of students whom they deemed at risk either personally or academically.

The results of this exercise often prove surprising: Some students may lack a single strong connection within school, while others may have many — far beyond just their classroom teachers. The Making Caring Common team also suggests that schools adapt this strategy to ask students to identify the adults with whom they feel connected. Comparing student and adult responses side by side can help to reliably surface the number of positive, stable relationships between students and adults. Armed with that set of data, schools can then consider how best to ensure that every student has at least one strong connection.

Given the particular challenges of this fall, mapping students’ relationships should also extend beyond the four walls of the school. Starting the year with a better sense of whom students can turn to outside of school can help educators learn more about their incoming classes of kids. For decades, social workers have used social network mapping, a close cousin to relationship mapping, to assess their clients’ support networks. Social network maps can help surface the connections students have in various domains of their lives beyond school, including older siblings, friends, extended family, members of their faith community and neighbors. Identifying these connections will equip educators with a better picture of whom their students can turn to for academic help and social-emotional support. From there, school districts can target and triage additional supports and outreach in response to students’ needs.

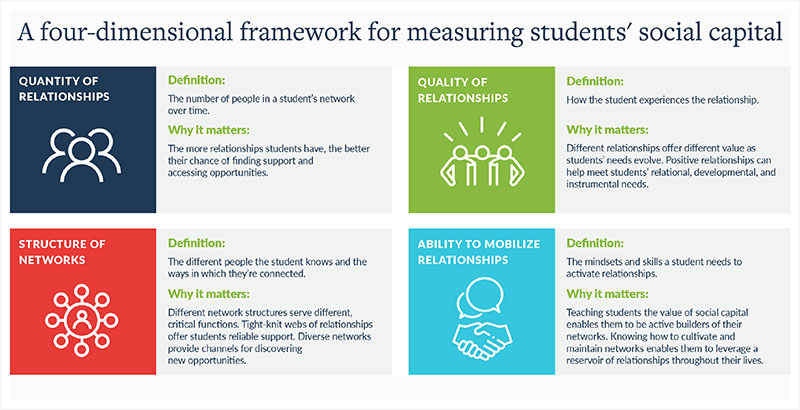

Relationship mapping is one of many promising strategies for understanding the nature of students’ networks within and beyond school. In our new paper, The Missing Metrics: Emerging Practices for Measuring Students’ Relationships and Networks, we highlight a range of practices that schools and nonprofits are starting to deploy to take stock of the relationship assets in their students’ lives. Some of those emerging strategies even empower students to identify and keep track of their own support networks. For example, iCouldBe, a virtual mentoring platform, guides students through activities to build relationships at school or in their community, based on their academic and career interests. In the course of the iCouldBe curriculum, students build their own online, dynamic relationship map that they keep up to date as their networks expand.

Schools that understand the quantity and quality of relationships at their students’ disposal will be well positioned to sustain their well-being and academic progress in the coming year, whether campuses open or remain closed. A healthy dose of advice is being doled out to administrators on how they might plan for fall; reworking schedules, retooling academics and investing in technology infrastructure can all help. But if schools don’t know whom students know and enlist those connections, how can they ultimately support them? Districts can’t have a complete back-to-school road map without a relationship map. Students’ success depends on it.

Mahnaz Charania, Ph.D., is a senior research fellow at the Clayton Christensen Institute, where she studies disruptive innovations that amplify equitable access to educational opportunities for underserved students. Julia Freeland Fisher is director of education research at the Clayton Christensen Institute and author of the book “Who You Know: Unlocking Innovations That Expand Students’ Networks.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)