Analysis: Internal Documents Show Few Union Members Volunteered for Massachusetts Anti-Charter Campaign

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears Wednesdays; see the full archive

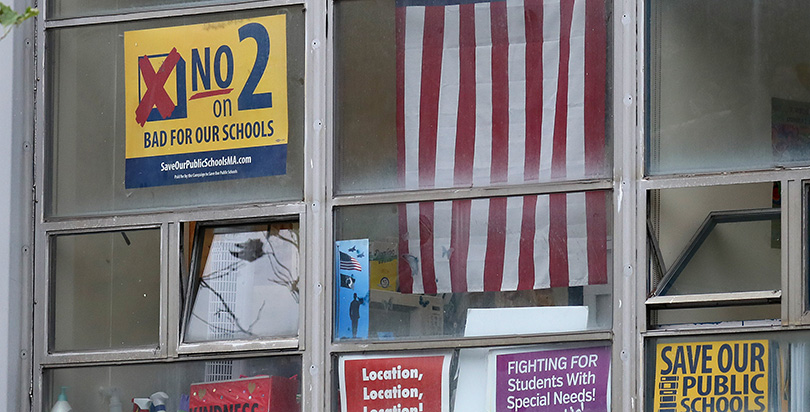

Question 2 on Massachusetts’s ballot last November would have allowed the state to approve up to 12 additional charter schools or expansions each year. The opposition, almost entirely funded and organized by teachers unions, handily defeated the referendum 62 percent to 38 percent despite being significantly outspent.

The Massachusetts Teachers Association still touts its victory, but an internal document indicates the “No on 2” campaign had its share of problems, not least of which was the small number of members who volunteered.

An internal overview of MTA’s effort sent to each union employee and manager who worked on defeating the referendum contains some self-congratulation but is also candid about complaints staffers had, primarily about their workload.

“Throughout the debriefs, MTA employees consistently expressed being both grateful for what the campaign accomplished and frustrated by it,” reported staffers Dan Callahan and Charmaine Champagne, who wrote the report. “The magnitude of the campaign brought with it a level of excitement that was unmatched by previous campaigns, according to many of our experienced staff members. At the same time, many staffers felt highly stressed throughout the campaign as they attempted to fulfill their regular work duties along with campaign directives.”

Unions commonly give some staffers leaves of absence to work on political campaigns, but the majority advance the union’s political work while still on the payroll. This means they have to process grievances, help negotiate contracts, address members’ legal problems, and perform communications activities along with the additional workload of a campaign. The report recommended that MTA should henceforth define which traditional tasks are “mission-critical” during election season.

The debrief also revealed just how much of the load MTA employees were carrying. For one, they were assigned mandatory phone-banking.

“Experienced staffers knew to expect this and kept their schedules open for October, but newer staff members may have been surprised by a sudden expectation to give up parts of their workdays or evenings to do campaign work,” the authors explained.

Callahan and Champagne noted another problem with phone-banking. “There was an appreciation for the quality of the scripts provided, but not all staff members had sufficient background knowledge in charter schools to be able to answer questions from people they were calling, or to know when and how to shift to a different argument that might work better,” they reported.

Staffers were also encouraged to go out and canvass. The union provided undisclosed incentives for this activity, but the authors stated that these were applied inconsistently and inequitably.

MTA saluted member engagement during the campaign, but the debrief suggests participation was limited. “On the face of it, only about 1 percent of our members engaged in MTA-run volunteer activities,” the authors stated. “While this percentage was higher than in previous campaigns, it felt low to many.”

Despite this, Callahan and Champagne concluded that members must have been highly active in informal ways, and that the No on 2 campaign “was clearly successful in ways that we were not equipped to measure, and missing out on this data is a lost opportunity.”

MTA is convinced its victory will lead to bigger and better things, although the authors acknowledged “it’s likely we will lose agency fee within the next two years, and we want to be prepared for that future.”

Organizing is key, they wrote, but staffers said that “everyone is operating under a different understanding of what organizing means.” They offered several suggestions to improve the union’s organizing structure, including one that responds to a schism among members between two different philosophies of the union’s mission.

I’ve described adherents of these ideas as movement unionists and services unionists.

The former believe people join unions to be part of the organized labor movement, to lobby, rally, agitate, protest and strike for a working-class agenda. That is why most movement unionists tend to be heavily involved in many leftist causes. The latter believe people join unions to improve their pay, benefits and working conditions. Though heavily involved in advocacy, much of it political in nature, the relationship of services unionists to their members is in many ways a commercial one. Fees are paid in exchange for services — contract negotiation, grievance processing, protection against arbitrary employment actions, liability insurance, and so forth.

One recommendation for MTA was “splitting the field into separate organizing and contract service positions.”

One recommendation for MTA was “splitting the field into separate organizing and contract service positions.”

It’s not clear whether this is realistic, but it would formalize the internal split by assigning staff to each function separately.

If MTA is representative of other teachers unions, they appear to be readier to learn the lessons of victory than those of defeat. A self-assessment might not be the most objective measure of their performance, but it’s better than no assessment at all.

NoOn2 Campaign Debrief by The 74 on Scribd

Email tips to mike@the74million.org

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)