Analysis: Illinois Set Ambitious Goals for Student Outcomes Under ESSA That Just Won’t Work. Here’s Why — and How States Can Do Better

The federal Every Student Succeeds Act requires state education agencies to set goals for student outcomes. In Illinois, the Board of Education has set a goal of having 90 percent of students achieve proficiency on state standardized tests. Although ESSA’s passage in 2015 was intended to usher in a new age of accountability, the board’s approach ignores one of the main lessons of the No Child Left Behind era (2002-15): Don’t set goals that schools have no chance of meeting, because schools will (appropriately) not take those goals seriously.

Moreover, the board’s goals continue to focus solely on proficiency, which is inconsistent with the state’s accountability system and with the emerging best practice in state measurement of school quality.

The board’s goal for proficiency is not connected to data about how much districts can improve. We know that in order for proficiency rates to increase, students will need to increase their learning at a rate greater than the current average, which is essentially one grade level per year. We have data to give us some guidance about what the best school systems are doing: compressing about six years of learning into five years.

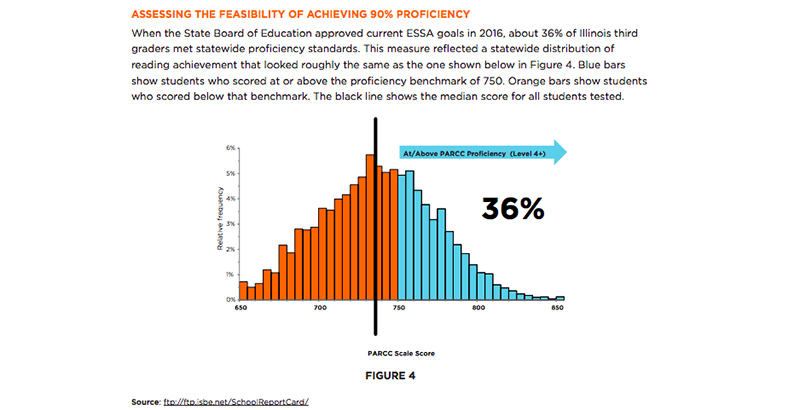

In Illinois, students are coming into third grade at approximately 36 percent proficiency. So if every school district in the state were performing at what are now the levels achieved by the country’s highest-growth districts, that would put us at 58 percent proficiency — still far short of the 90 percent level. The state board’s articulated intent was that the 90 percent goal would underscore its commitment to helping all students, but the board actually undermines that commitment by setting expectations that cannot be met. NCLB set a goal of 100 percent proficiency by 2014, and part of why it became irrelevant is that everybody understood that the goal had no chance of being achieved.

We value the use of proficiency as part of the state’s goals, as we want students to be achieving at grade level or above. The bipartisan consensus behind NCLB in 2002 reflected a strong desire by federal leaders to demonstrate a commitment to improving student achievement. But the bipartisan consensus behind ESSA in 2015 reflected an understanding that proficiency alone is a limited measurement. Indeed, given the value of growth measures — and the fact that growth is part of the accountability system under ESSA — state agencies across the country should demonstrate that they understand the relationship between growth and proficiency. Improving proficiency requires students to grow at accelerated rates, so goals should reflect realistic expectations about the rate of growth.

How can states do better?

First, they should set goals based on the data and research we have. Then, each school should be given the tools to determine what its leaders think it can accomplish. Should schools be pushed to be ambitious? Of course — we need to acknowledge that our students need to do better to meet the challenges of the 21st century. But unless schools and communities believe their goals are relevant, they will not make the changes necessary to meet those goals. While Illinois’s targets are more ambitious than the national average, a survey by Achieve Inc. shows that the state is not an outlier in either math or English Language Arts.

Second, to really meet aspirational goals, we need to focus where we have the most leverage. Too little attention has been spent on using early childhood education to support long-term progress toward college and career readiness. As important as it is to strengthen the school experience from third grade on, the highest-leverage strategy we have is to focus improvement efforts on the years before third grade. Our willingness to invest in early childhood education will be a true test of our belief in our systemwide goals at the school, community, and state levels.

Third, we need to focus on moving all students forward. Data at the school, district, and state levels show that gains in achievement among lower-achieving students rarely, if ever, occur at scale without comparable gains among average- and higher-achieving students. Simply focusing on lower-achieving students does not create the environments that truly move the needle on proficiency.

Finally, we need to ensure that we have a fuller, more complete picture of what readiness is. Students who are proficient on state assessments — especially on new rigorous state exams — are likely to be academically prepared for college. But being ready requires more than that; it takes self-discipline and self-confidence, the ability to show up on time and be able to link academic learning to real-life experience.

Similarly, students who do not quite reach the high academic bar set by our new assessments in both math and English may have strengths in other areas. We need to provide the space for them to demonstrate what they are ready for in a variety of ways. This does not mean ignoring standardized test results, but integrating them with other information that we have about students’ academic, social, and emotional skills.

We appreciate the need for goals to be ambitious, and every student truly deserves the chance to succeed. But goals that make no sense will lead to improvement plans that make no sense. Illinois’s current goals are a well-intentioned distraction from the improvement process we need to have in place; they should be changed to reflect the current reality while putting us on a path to a better one.

States must be clear-eyed about what schools can accomplish, when they can accomplish it, when they are succeeding, and when they are not making the grade — and their state goals should reflect not just their best aspirations but their facts on the ground.

Elliot Regenstein is a partner at Foresight Law + Policy, a national education law firm based in Washington, D.C. Ben Boer is former deputy director of Advance Illinois. Paul Zavitkovsky is an assessment specialist for the Center for Urban Education Leadership at the University of Illinois at Chicago. They are co-authors of Establishing Achievable Goals, an analysis of the Illinois State Board of Education’s goals under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)