Analysis: How to Equip Educators to Shift From Traditional to Student-Centered Teaching? With Microcredentials That Build on Each Other

The clamor to equip teachers to respond flexibly to another uncertain school year has brought to the forefront a problem that has impeded schools for years, albeit in a less obvious way: Teachers need an updated skill set for the modern world. The basic structure of the classroom is shifting from the monolithic, standardized model of the Industrial Era to a flexible, student-centered model for the Networked Era. But many teachers and school leaders, despite their excellence in traditional instruction, lack the skills to make the shift.

Student-centered schooling has several definitions, but a few elements are common: learning tailors instruction to each student’s gifts and circumstances; students have the technologies plus individual prerogative to drive their own learning, rather than relying primarily on the teacher; and students progress as they demonstrate competency, rather than through the passage of time.

These elements make student-centered schools generally well-suited to respond flexibly to the COVID-19 fallout. In particular, where students are encouraged to drive their own learning, they can toggle between face-to-face and remote instruction with comparative ease. This enables them to make progress without an in-person teacher presenting lessons from the front of the classroom. At the same time, the teachers’ role changes: Rather than delivering lectures, they look for ways to give their students personal capacity and a can-do mindset. In sum, both the students and the teachers require fewer adaptations to switch from an in-person to a remote plan.

What’s the most feasible way to equip millions of educators to shift from traditional to student-centered teaching? Is there a way to name and develop educator skills for student-centered teaching collectively, rather than each school inventing a solution? What innovations are best suited to accomplishing this?

Thomas Arnett, senior research fellow at the Clayton Christensen Institute, Allison Powell, director of the Digital Learning Collaborative, and I tackle these questions in a new Christensen Institute report: “Educator Competencies for Student-Centered Teaching.” There are roughly 4 million preK-12 teachers in the U.S, whose credentialing programs by and large prepared them to operate in traditional settings. If a solution exists to give this army of teachers a reasonable path to develop new skills for today’s complex and networked reality, we wanted to find it.

One takeaway from our research stood out: Among the various methods for educator professional development in use today, microcredentialing is the one to watch. Microcredentials are digital certifications that verify a teacher’s accomplishment in a specific skill. To earn a microcredential, educators must submit evidence — such as a classroom video, student surveys or a lesson plan — to demonstrate their ability to put into practice a skill, such as giving students quality feedback, creating real-world projects or assessing individual student needs. Educators can start and finish a microcredential whenever they want. BloomBoard and Digital Promise are among the most prominent groups issuing K-12 educator microcredentials in the U.S.

Microcredentials have the makings for a modular architecture, which means the component parts stack together interchangeably, like the predictable click of Lego bricks as they lock together. As such, they can reduce the costs, ease the setup and enhance the customizability of student-centered professional development.

For example, schools often design their own internal teacher training in collaboration with consultants. This approach can be time-consuming and expensive, requiring significant expertise. In contrast, administrators can outsource the delivery of microcredentials, with economies of scale lowering the cost.

Another type of professional development involves partnering with a provider that offers a bundle of comprehensive learning resources, such as Summit Learning, Acton Academy or New Classrooms. Schools then adopt the whole package as one integrated bundle. This strategy provides a complete solution that’s been rigorously tested and improved. But it requires conformity to the external provider’s model. Schools with unique needs might not find one that fits. In contrast, microcredentials can be stacked together in any number of ways to meet the needs of a wide variety of school needs.

However, microcredentials will need to be designed and used strategically to unlock the benefits. For example, providers should be meticulous in writing their microcredentials according to schools’ specific requirements. If a principal needs a teacher who can give high-quality feedback to third-grade English learners, the microcredential must match that specification. Meanwhile, schools should scrutinize microcredential providers to ensure that they reliably assess teachers’ skills.

Another finding from our research is that the education field is getting closer to reaching a rough consensus on the student-centered skills that educators need.

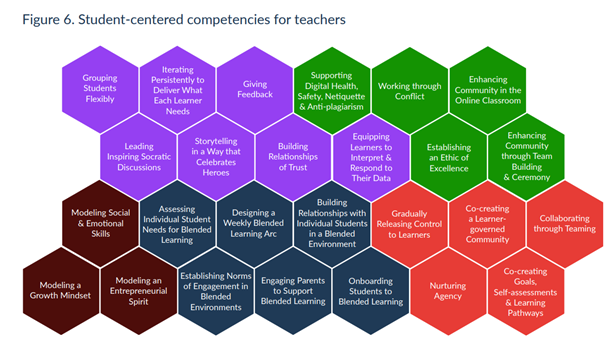

In February, 25 leaders in student-centered education convened to create a list of skills so providers can develop microcredentials that precisely match those specifications. By the end of the process, a working hypothesis emerged. Although the map is a work in progress, it offers a starting point and indicates where student-centered professional development should head.

The graphic below shows five clusters of competencies that the group identified for teachers. There is a different set for school leaders and design teams. Altogether, the complete map for all roles has 13 clusters and 66 skills, which schools can mix and match.

As schools shift to student-centered learning, microcredentials are poised to bring the benefits of a modular solution for professional development. While other options tend to be difficult, time-consuming and expensive to develop, or require conformity to an external provider’s model, a truly modular system, however, provides reliable certification of educator skills and adapts to a variety of models in an affordable, easily set up and customizable way.

Microcredentials could unlock that potential, if structured and managed well. The key is to shape them to match the specific needs of schools and to ensure that educators who complete them are evaluated in a verifiable, predictable way.

Much work remains, but a path is emerging for equipping teachers with the skills that will enable them to give each learner a student-centered education. In the short term, schools should consider using microcredentials to equip their teachers with the specific skills they need right away to get through this school year.

Heather Staker is an adjunct fellow for the Christensen Institute and the co-author of the books Blended and The Blended Workbook. She is president of Ready to Blend. Follow her at @hstaker or on the Ready to Blend podcast.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)