Analysis: How Schools Could Be Closed for More Than Five Months and Still Spend More Than They Did the Year Before

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears most Wednesdays; see the full archive.

The COVID pandemic ensured that the 2019-20 school year would be remembered for classrooms shutting down and districts struggling to provide online instruction to students, many of whom were disengaged or just AWOL. It was an unprecedented and revolutionary change for U.S. school systems.

One thing didn’t change, however. They still spent more money.

It might be difficult to understand how schools could be closed for more than five months out of the fiscal year and still spend more than they did in 2018-19. It might be especially confusing because spending on student transportation fell by 5.7 percent and spending on food services dropped by almost one-third, according to preliminary data from 35 states and the District of Columbia compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau.

But it’s surprising only if you don’t know how spending on K-12 public education is allocated among various priorities.

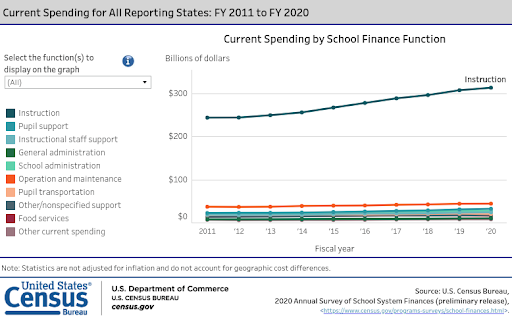

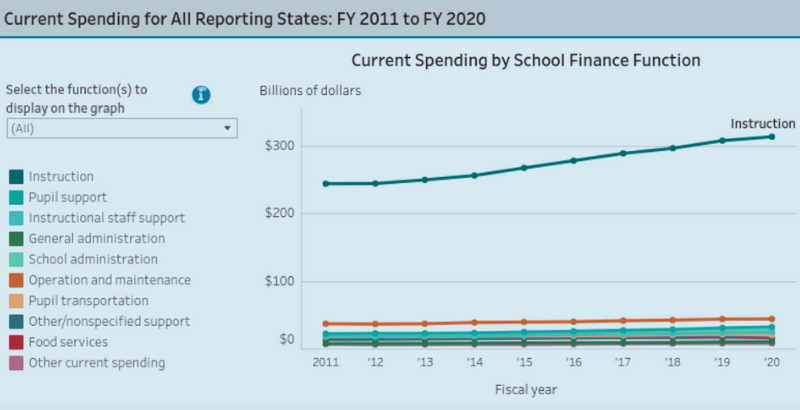

Most statistics break down education spending by function: instruction, administration, transportation, maintenance, food services, etc. Described this way, it’s only natural to want the bulk of spending to go toward the primary purpose of schools: instruction. And it does. About 61.2 percent of current school spending is devoted to instruction.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much evidence that increasing spending on instruction actually improves instruction. About 15 years ago, there was a movement among school reformers dubbed the “65 percent solution,” which would have required school systems to spend at least 65 percent of their budgets on instruction. It was a hot trend for a while, even though it was lambasted both on the left and the right.

Nevertheless, looking at the trend since 2011, instructional spending has steadily increased, while spending in all other areas remains relatively flat.

Since we’re spending extra money on instruction, what exactly are we buying? Textbooks? Technology? Curricula?

A further breakdown indicates 89 percent of instructional spending is used for employee salaries and benefits. Of course, schooling is a labor-intensive enterprise, and you can’t have instruction without instructors. But that 89 percent actually underestimates the percentage spent on personnel.

Another 5 percent of instructional spending goes toward “purchased services,” which the National Center for Education Statistics tells us includes “purchased professional services of teachers or others who provide instruction for students.” These are independent instructors who may be brought in for a special or temporary purpose.

Instructional spending is people. If it goes up, it means you’re hiring more, and/or paying the ones you have more. The latest Census Bureau numbers bear that out. The bureau concludes that “increased spending in instruction and teacher salaries offset notable decreases in spending on student transportation and food services.”

Something else didn’t change during the COVID school year. School revenues from all sources in the 35 states and Washington, D.C., in the Census Bureau report increased 2.2 percent from 2019. However, spending increased 2.5 percent.

The Census Bureau won’t have data from all 50 states until May. Even then, it won’t include the full impact of the additional billions provided by the federal CARES Act or the American Rescue Plan. What’s certain is that schools are adding employees while losing students. When the money dries up and the layoffs occur, will people remember that the decisions of today made it inevitable?

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)