Analysis: ESSA Offers a Real Chance to Drive Real Change in America’s Schools — but Only If We Follow the Evidence

Federal policymakers have been working to reduce massive disparities in educational outcomes for youth in America for 60 years, with disappointing results. Fortunately, the newest iteration in our nation’s quest to address persisting education challenges, the Every Student Succeeds Act, looks very different from past attempts.

The key to the new law is that it gives states and local districts new authority to design education systems that reflect their needs and priorities, provided the new designs are based on evidence. If state and local leaders fully embrace the law, it’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity to change the status quo in education.

If implemented well, ESSA could ensure that more resources — up to $2 billion annually — are invested in solutions that have a proven track record of improving student outcomes. Those investments could help decision makers make better use of data and evidence of what works in education, which in turn might encourage further study and ultimately generate new evidence. If these evidence-based approaches are replicated to scale, we might finally see a marked shift in our approach to education policy, rather than the incremental changes we’ve seen so far.

The data are essential to success. Current experiments in education reform are already fostering compelling shifts in learning approaches. For example, many schools and districts are implementing a strategy that integrates academic, social, and emotional development of children, because there’s evidence that it boosts all the indicators we already measure. A council of distinguished scientists unanimously agreed, noting that the approach boosted metrics such as grades, standardized test scores, social interaction, graduation rates, and college success. It’s already paying dividends: Tacoma, Washington; Fresno, California; Cleveland, Ohio, and other districts have adopted this approach with impressive results, particularly in turning around low-performing schools.

We’ve learned lessons from past experiments, too. We know the transformative power of Early Warning Information and Intervention Systems to signal trouble and prompt tailored interventions to prevent kids from dropping out; of career academies and early-college high schools that heighten the relevance of education and provide pathways to college and employment; of restorative and positive disciplinary approaches that ensure students are invested in addressing the underlying conditions of disruption and take responsibility for their actions; and of leveraging national service teams of peer mentors and tutors to increase attendance and achievement rates. Schools do better when they use evidence to establish core environmental and learning practices.

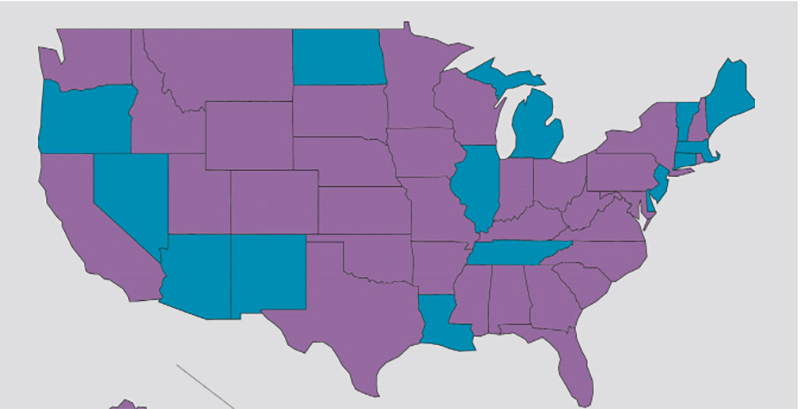

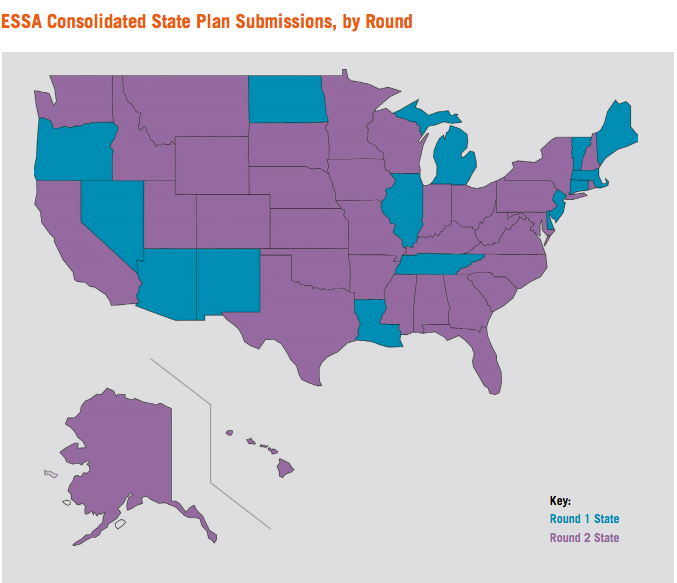

It’s hard to know the extent to which these lessons will materialize in ESSA implementation at this early stage, but preliminary observations give cause for both hope and alarm. Many states have fully embraced their newfound flexibility, yet glaring deficiencies remain for far too many others. In a recent report on all 50 states, Results for America identified 13 promising practices that states could use to build evidence to improve student outcomes; 90 percent of states are including at least one of these practices in their reform plans. Fourteen states have shifted from population-based funding models to allocating resources based on their districts’ and schools’ plans to use evidence-based interventions.

Some states are building networks focused on using evidence and continuous improvement. A partnership of stakeholders in Nevada created a community of practice for schools to learn from one another about implementing evidence-based approaches to school improvement. Tennessee and other states have developed formal research partnerships with top universities to conduct independent evaluations, help design and implement research-backed interventions, and provide timely information to state policymakers across a variety of areas, including early reading, professional learning, school improvement, and education for the workforce.

The good news notwithstanding, early evaluations of ESSA show a long road ahead, mainly due to the low take-up rate of potential evidence-based policy tools by states. A meager three states have strong plans to prioritize the use of evidence and continuous improvement to turn around persistently failing schools; a modest nine states emphasized the use of evidence and continuous improvement in their school improvement applications. And no state articulated a clear vision for using and building evidence outside of Title I school improvement — neither in Title II for professional learning, nor in Title IV for student supports, two of the most critical areas in which policy and practice should be informed by evidence.

Despite these early missteps, we are optimistic. The new law has shifted the education landscape, with promising gains on the horizon. State and local leaders asked for greater authority, and now, they have it; all eyes are on them as they exercise greater flexibility. But with that flexibility comes new responsibility, and we urge them to seize this opportunity to align innovation with data, evidence, and continuous learning. We’ll get the best possible education outcomes, and ultimately, all our children — in every community — will have a better chance to succeed.

Melody Barnes and John Bridgeland served as directors of the White House Domestic Policy Council under former presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, respectively. They are senior fellows at Results for America.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)