Analysis: As a Nervous Summer Begins, Schools Scramble to Fill Job Vacancies

Idaho has hundreds of teacher vacancies and school districts are having a hard time finding qualified candidates

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It’s the start of a nervous summer for school superintendents and H.R. folks.

Idaho has hundreds of teacher vacancies, and many schools can’t find qualified applicants. That could translate into unfilled positions and larger class sizes — and inexperienced teachers in hard-to-fill disciplines such as math, science and special education.

Idaho schools are fully feeling the pressure of a larger 2022 job market. And their nervous summer comes after what was, by the numbers, a good winter for education. The 2022 Legislature put an additional $104 million into teacher pay, and $180 million into improved benefits for school employees. That should add up to more take-home pay, but still might not prevent a teacher shortage.

As one Treasure Valley administrator put it recently, “The crisis that we have been talking about for the last 10 years is here.”

“People are leaving education,” a Magic Valley administrator said. “We need help.”

The numbers only tell part of the story

To attach some numbers to the problem, the State Board of Education conducted an informal survey.

The results are incomplete. The State Board only surveyed school districts — not the charter schools that serve nearly 10% of Idaho’s students.

And the results are fluid. A week ago, the State Board tallied 894 teacher vacancies (Boise-based KTVB reported these numbers on June 2). The State Board updated its count this week; recent hires brought the number of vacancies down to 702.

Either way, these vacancies reflect less than 5% of a teacher workforce of more than 18,000. But the numbers only tell part of the story.

Timing is a big concern. Usually, schools have their teacher vacancies filled by now — with new hires in place well before the fall. That isn’t the case this year, and “now we’re entering the dry period,” said Tracie Bent, the State Board’s chief planning and policy officer.

Bent can sense that districts are worried, and she has some solid anecdotal evidence. The State Board’s anonymous survey was optional. But administrators from 90 of Idaho’s 115 school districts used the survey as an opportunity to sound the alarm.

‘What pool?’

Of course, vacancies are just part of the H.R. equation. Another piece, equally as important, is the number of applicants.

Asked about the applicant pool, compared to previous years, one East Idaho administrator minced no words. “What pool?”

Across the state, administrators report the same thing. A shortage of qualified applicants — and not just in areas such as math, science or special education, where candidates are generally hard to come by.

As a result, schools are almost sure to fill more of their vacancies by hiring teachers who have gone through alternative certification programs, rather than the traditional path of graduating from a college of education.

This isn’t a new trend. In 2020-21, nearly 700 new educators received an alternative certification, according to a State Board “educator pipeline” report completed in March. For the first time in state history, this number of alternative certifications eclipsed the total number of students who completed traditional programs at Boise State University, the University of Idaho, Idaho State University and Lewis-Clark State College.

Hiring from alternative programs raises short- and long-term questions. Are these new hires prepared to step into a classroom immediately? And do these alternative hires stay in the profession for the long haul? The March State Board report revealed a significant dropoff in retention rates for teachers who go through the American Board for Certification of Teacher Excellence — the alternative program of choice for most Idaho teachers. One possible reason: ABCTE graduates receive three-year interim certificates, leading to a retention cliff in Year Four.

It’s all about the money — or is it?

The State Board will discuss the survey at its meeting next week. But the board will not take action, and will receive no recommendations from staff beforehand, Bent said.

But from a policy perspective, state leaders have already spent years trying to address the teacher retention issue. Many of those efforts have been focused on the bottom line: pay and benefits.

Seven years ago, the state adopted the “career ladder,” a teacher salary schedule designed to improve Idaho’s chronically low educator salaries. The ladder appears to be paying dividends, according to the State Board’s March “educator pipeline” report; retention rates approached 92% in 2019-20, up nearly three percentage points over five years.

The 2022 Legislature used a combination of state money and federal coronavirus aid to pump an additional $104 million into the career ladder — although some schools are using the one-time federal money for one-time bonuses or stipends, rather than ongoing pay raises. And the $180 million for benefits is designed to save teachers on the out-of-pocket cost for health care, which is tantamount to a pay raise.

Yet even so, schools are staring at the prospect of teacher shortages come fall. And in the recent State Board survey, some administrators say the state should consider stipends to cover relocation or rising housing costs — augmenting raises that don’t always keep pace with inflation or salaries in neighboring states.

“This is a problem that we all saw coming — very low wages compared to other states,” one Magic Valley administrator wrote. “Now the cost of living has outpaced annual raises and there is no available affordable housing. Perfect storm.”

The housing crunch is a definite factor, among many factors, Idaho School Boards Association deputy director Quinn Perry said this week.

“We can no longer just point and say, ‘Increase teacher salaries,’” she said. “It goes so much deeper and further.”

A question of respect

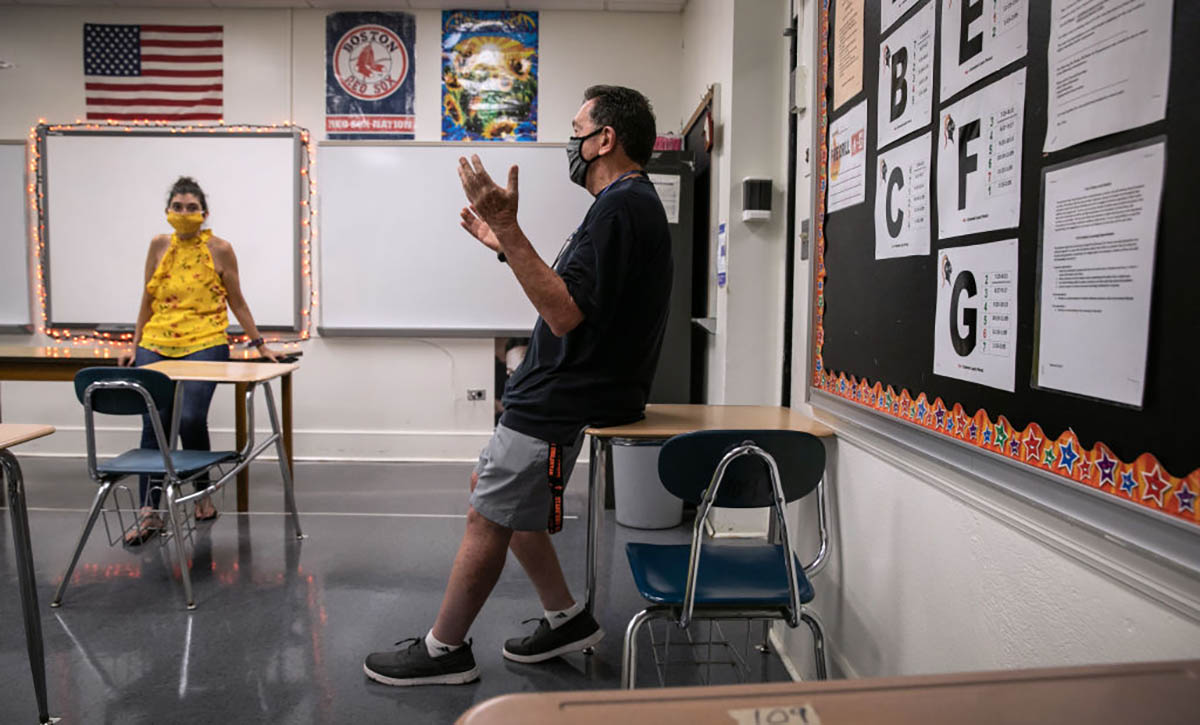

This year’s investments in pay raises and benefits come after two unusually trying years in education. The stress of COVID-19 closures, and the abrupt shift to online instruction. The uncertainties of moving back to face-to-face learning in the middle of a pandemic. The challenges of helping students overcome learning loss and mental health crises. The nationalized backlash over critical race theory.

“It is more than salary,” said Perry. “It is more than pay. It is respect for the profession.”

The State Board’s educator pipeline report warned of a gathering storm.

“There are early signs that the changing social and political context of public education may soon lead to an increase in educators leaving the field early,” wrote Nathan Dean, the State Board’s educator effectiveness program manager.

This year’s raises and boosts to benefits represent an “important step forward,” Idaho Education Association spokesman Mike Journee said this week. But he said the 2023 Legislature needs to do more to make teaching jobs more attractive — from addressing school safety and student mental health to recognizing the “nobility” of the profession.

“That’s what we have to change, and that’s what we’re going to be fighting for,” Journee said.

But before the 2023 legislative session, schools need to get through a nervous summer in the labor market.

Kevin Richert writes a weekly analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for his stories each Thursday.

Idaho Capital Sun is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Idaho Capital Sun maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Christina Lords for questions: info@idahocapitalsun.com. Follow Idaho Capital Sun on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)