An Autistic Girl in the Cumberland Mountains: One Family’s Brutal Fight for Meaningful Special Ed

Haysi, Virginia

Glennis and Randy Looney let their guard down for only a moment.

Sitting on a sofa in their wood-paneled living room, they were recounting the continuing struggle to persuade schools in Dickenson County to provide their 12-year-old daughter Abigail, who suffers from severe autism, with more help.

Abigail wandered through the house, her ponytail falling forward as she scoured the refrigerator — repeatedly — for asparagus. Then she ran to her father on the couch. With her face pressed against his, she whispered, “I see you” — a line from the movie Avatar. Abigail was echoing speech Randy had said to her before.

Then, knowing her parents were talking about her, she sat on the couch’s armrest and jammed her fingers into her ears to block out the sound. Slipping outside, she bounced one of the balls she collected obsessively. She had more than 100 at one point, and each one gave a different sound when it smacked the ground.

It was around dusk when they noticed Abigail was gone. Like a lot of children with autism, she bolted occasionally.

The Looneys’ home, reached by a dizzying gravel road, sat on a ridge in the Cumberland Mountains, and it was getting dark. Randy stepped outside to follow the sound of bouncing. An apple minus one bite lay on the ground.

He rushed around front, toward the thumping, but Abigail wasn’t there. Instead, it was a different girl, a neighbor, playing basketball by herself. For a second, Randy’s face became expressionless. In one motion, he jolted back inside, jumped into a pair of boots and sprinted down a hill to the small fishing pond on the edge of their property. Abigail couldn’t swim, but she had tried. As he approached the water, he yelled her name, hoping that a girl who couldn’t hold a conversation would make a sound.

Glennis took off in their golf cart the other way, farther up the mountain. Abigail rode in the cart whenever possible, and Glennis hoped the gargle of the small engine might draw her out of the woods. A few minutes later, it did.

Glennis was visibly relieved as she drove her daughter back to the house, but even as Abigail giggled uncontrollably from the passenger seat, her mother knew another eruption would come that night.

Sure enough, a few hours later, for no apparent reason, Abigail stormed out of her bedroom, blood rushing to her face as she screamed. Together, the parents rushed to their only child and lowered her to the kitchen floor, hardly able to stop her from gnawing on her own wrists.

Abigail Looney, who has autism, screams at the top of her lungs as her parents, Glennis and Randy, prevent her from biting her wrists. The parents learned to slip protective guards on her wrists when she began to panic. (Photos by Mark Keierleber)

Worse in sixth grade than in first

It was not always so.

Abigail had been a fragile infant. Born weeks premature, she underwent several surgeries while still a baby. By the time she turned 2, she had stopped making eye contact. Even her most basic communication skills vanished. The Looneys traveled across the state to experts at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. A doctor there diagnosed autism.

“Even now, my heart bursts nearly daily, and I still don’t know what to do,” Randy said. “That was the toughest thing I’ve ever had to swallow in my life. Talk about a world, your whole world, just imploding.”

The couple knew little about autism, let alone the complexities of federal law for students with disabilities, which before long would become the staging ground for the most important battle of their lives. A Colorado case the U.S. Supreme Court will soon consider could have huge implications for the Looney family, and others like them, when the court weighs the level of education services that public schools must provide disabled students.

From kindergarten to second grade, Abigail was included in the general classroom at Sandlick Elementary School, in nearby Birchleaf. Glennis and Randy hoped that interaction with “normal” peers would be a big advantage.

“We thought, ‘Great, she is going to pick up on all kinds of things,’ but it didn’t happen,” said Randy, a disabled coal miner whose Wranglers and Cabela’s sweatshirt squarely identify him as an outdoorsman. “She didn’t pick up on anything, really.”

But while her abilities to communicate and interact were impaired, Abigail demonstrated an ability to learn.

Evaluations in kindergarten and first grade show she worked to complete tasks and became more adroit at answering questions and communicating wishes; evaluators noticed she used her mother’s transitional call — “five more minutes”— when she wanted to keep playing.

Now, with Abigail as a sixth-grader, her language skills and behavior were worse than five years before, the Looneys said. Abigail wore diapers to school and in angry episodes bit herself and kicked a bookshelf. She was put on medication to calm her outbursts, but it left her constantly hungry and caused dramatic weight gain.

At home, Abigail left Randy with scars on his forearms and punched cracks in their mirrors. She ripped chunks of hair from Glennis’s scalp and left her mother with bulging black eyes. She once kicked her grandmother so hard she went barreling through a closet door.

For the Looneys, the cause of her regression had been obvious for years: Local schools were failing her, literally making her sick.

The Looneys said Abigail’s condition worsened when she was moved to a new school for fifth grade without proper help for her transition. The transfer began a downward spiral she never recovered from, her parents believe, and was worsened by yet another move for sixth grade. For some people with autism, shifts in routine can be intensely destabilizing.

Neither school was adequately trained to handle her disabilities, the family argued repeatedly in meetings with district officials. The county school system had just one professional trained in a technique to address severe autism — a contractor who worked in Dickenson County schools for only one day every two weeks.

Yet in meetings, school officials didn’t budge. Not only were they able to provide the girl with an appropriate education, they said, but she had excelled on a state test designed for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Randy and Glennis didn’t believe that could be so.

Abigail, whose vocalise consisted of humming, burbling, lip-strumming and screaming — but not “communicating” — couldn’t say “I love you” at home. But at school, officials said, she could identify U.S. presidents and Virginia’s role in the American Revolution. She could cite the theme of poems, they said.

Portraits of Abigail adorn the walls and cabinetry in the family’s rural Virginia home.

Glennis and Randy felt unequipped to prove the school officials wrong. They sent along warnings from her doctors that Abigail would need to be institutionalized without “intensive interventions” that local schools could not provide.

“Be honest within yourself — there’s no way that this school system, in this public setting, can provide her needs,” Randy said in a meeting last fall. “Our daughter is severely autistic. I mean, there comes a time when we need to say, ‘Hey, she’s more severe than what we can actually handle.’”

Mentally, Abigail had been missing for years, Randy felt.

“For a while there I felt like I lost, literally lost, my daughter every day,” he said. “Every day was like I lost her. It was all new, every day. And then in a certain sense we did.”

Unswayed, the district — which declined to answer questions about Abigail’s case or special education in county schools — refused to sign off on a transfer to a private school that focused on children with autism. It wasn’t necessary, they said, because “we can serve her needs.”

Following the doctors’ advice, the Looneys pulled Abigail from school last year.

Isolated and autistic in rural America

They felt alone, unaware that thousands of parents with young autism sufferers were also battling school districts around the country, sometimes for years, even in other rural Virginia counties. With many of these families, fighting to give their disabled child the best possible school experience had become the central effort of their lives.

Federal law stipulates that every disabled child is entitled to a free “appropriate” public education in the “least restrictive environment” — alongside non-disabled students, to the greatest extent possible. In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the law — known today as the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) — did not include a “substantive standard,” only that schools provide “some” benefit, a “floor of opportunity.”

The decision has long disappointed disability advocates, who hope for a more equitable ruling after the court hears a new case, Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District, a 10th Circuit decision upholding a Colorado school district’s refusal to reimburse the parents of an autistic student for private educational services. The district claimed it provided the student with “some” educational benefit.

IDEA has been one of the nation’s most-litigated federal statutes because no plan for a child is innately “appropriate.” While any plan can be disputed through mediation and due process, most families can’t afford to engage in such battles, said Ruth Colker, a law professor at Ohio State University who has written extensively on inequalities in special education. School districts with larger low-income populations often are unable to provide programs afforded to children in middle-class and affluent school districts.

Autism complicates matters further, because even highly disabled students can improve substantially — but sometimes only in specialized private schools with six-figure tuition fees. The Supreme Court found in 1993 that, if a public school district was unable to provide an appropriate education, the district was responsible for a family’s private costs.

The extraordinary rise in autism diagnoses in the past 15 years has brought with it a clinically supported demand for expensive private interventions.

Whereas one in 2,000 children was deemed autistic in the 1980s, the numbers began to rise around the turn of the century, and by 2012, one in 68 children was diagnosed with autism, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Between 2002 and 2012, autism more than doubled in prevalence — with diagnosis typically occurring before grade school and with boys four and a half times more likely than girls to have the disorder.

In schools, the population of students with autism has risen in virtually every state, the total growing from about 90,000 15 years ago to more than half a million in 2013–14.

This dramatic shift has “challenged special education to the core,” said Daniel Unumb, executive director of the Autism Speaks Legal Resource Center.

“Here you have a condition that can be extremely disabling but at the same time is highly susceptible to dramatically being improved with appropriate interventions,” Unumb said. “You can have a child who comes in who is nonverbal, who is self-injurious, who may be aggressive, [and] that child, with appropriate interventions, can ultimately be mainstreamed in public education, can relate to other kids, will hold a job, will go on to higher education.

“That’s incredible stakes to be presented with, for all involved.”

The increase in autism isn’t entirely understood, but researchers attribute some of it to shifts in diagnostic norms, some of it to environmental factors, and some to genetics. It is also associated with huge costs. While school expenses are notoriously hard to pin down, the latest major study, funded by the U.S. Department of Education more than a decade ago, found that states spent $50 billion on special education students.

On average, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, annual costs associated with a school-age child with autism like Abigail, with deficits in her abilities to learn and adapt, total more than $85,000.

In Virginia, student autism has increased by 300 percent since 2004, said John Eisenberg, who oversees special education for the state Department of Education.

“About half of that population of kids are kids with pretty severe autism who need lots of intense supports,” Eisenberg said. He has called the medical challenges facing these children “some of the most complicated issues that school divisions [districts] face.”

The startling allegation that Texas set artificially low limits for more than a decade on the number of students eligible for special education, even as autism rates grew, appears to be an unusually systematic attempt to control costs by limiting services.

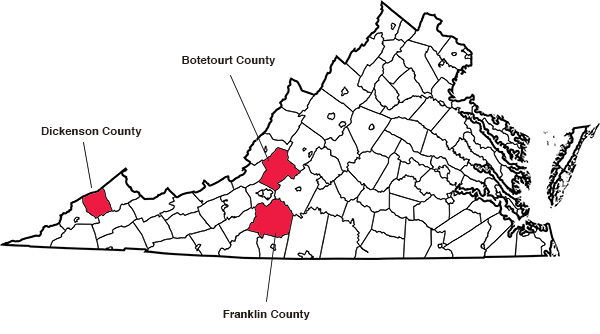

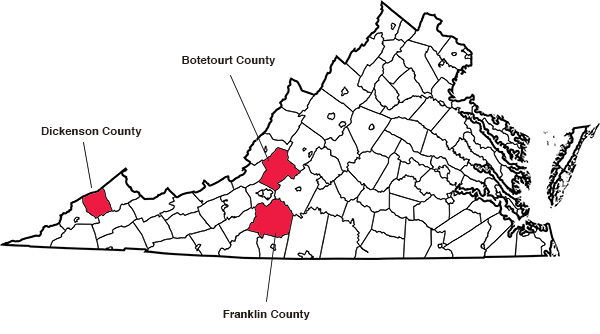

Beyond the cost, the Looney family’s isolation was another obstacle to Abigail’s improvement. The help she needed was far from Dickenson County, a sparsely populated, fading coal region — best known for producing the iconic bluegrass singer Ralph Stanley — where 30 percent of adults lack a high school diploma.

Roughly 80 percent of schools in rural areas nationwide have reported shortages in special education staff, with unqualified educators often filling vacancies.

On its interactive map, Autism Speaks shows no “autism providers” within 40 miles of Clintwood, the Dickenson county seat where Abigail attended middle school (and, with 1,500 residents, the county’s largest municipality). Bristol, a 90-minute drive south, is the only town of more than 10,000 people within a three-hour radius.

In a very different part of the state, among wealthier and more populous Washington, D.C., suburbs like Fairfax, those with autism were served by 47 providers in a 25-mile area (not including the District).

Dickenson County had little reason or ability to create economies of scale for serving severely disturbed students; there just weren’t enough Abigails. Given the challenge of attracting qualified educators to the county’s hardscrabble villages, let alone board-certified behavior analysts, it was unlikely that Abigail could receive access to the care that students in less isolated areas enjoyed.

Indeed, battles similar to the Looneys’ were being fought at the same time in other rural areas of the commonwealth. Virginia education officials maintain that few disputes over special education services are so protracted that they result in formal due process decisions by the state. Meanwhile, a group of special education parents in Franklin County, south of Roanoke, compiled a record of alleged malfeasance that sparked a state investigation.

A family in Botetourt County pushed to get the local school to move their son to a private facility for autistic children — school staff retaliated, the family said, sending the sometimes incontinent teenager home with his feces in his backpack.

‘Be careful about what you do and say’

When Abigail was in third grade, during the 2013–14 school year at Sandlick Elementary, her erratic behavior reportedly began to distract other children, and she was moved into a self-contained special education classroom with fewer students, though none as profoundly affected by autism. When she remained unable to communicate, her parents began questioning the quality of her instruction. They felt her Individualized Education Program (IEP) goals were structured to satisfy a state test, not to meet Abigail’s individual learning needs.

“Basically, I felt they were trying to babysit her and get her through the day,” Randy said. “I told them, ‘You know, we don’t want a babysitter. We want our child to be able to learn something.’ She’s in third grade now and she can’t say ‘I love you, daddy.’ ‘I want a glass of milk.’ ‘My tummy hurts.’ Nothing.”

They had signed off on Abigail’s IEP, but only reluctantly; like other parents unhappy with their disabled child’s experience, they feared she might not receive any help if they explicitly bucked the school.

But they had complaints: Abigail received only a fraction of the speech and occupational therapy she needed, her progress couldn’t be measured effectively, and goals were unrealistic given her challenges. They took their concerns to the district superintendent and director of special education.

Randy argued that Abigail’s teacher was inadequately trained. There was no way anybody could learn to work with profound autism using online courses, he said.

Denechia Edwards, the director of special education, cut in.

“Randy, you need to be careful about what you do and say,” the Looneys recall her saying, though the meeting wasn’t recorded. “The actions that you take may determine and influence the quality of your daughter’s education and care.”

Randy has a calm voice but also has a temper, especially with regard to Abigail, and he literally jumped out of his chair. He jabbed his finger forward.

“Denechia Edwards,” he said, “it is your job to make sure that that doesn’t happen.”

He turned to Haydee Robinson, the superintendent: “It is your responsibility and duty to make sure that she does her job.”

The Looneys, like the family in Botetourt County, believe that after that meeting the district began to retaliate against them for insisting that Abigail’s services were inadequate.

“The threat that [Edwards] made, she stood good on,” Randy said. “She made it happen.”

Robinson did not respond to requests for comment.

Randy chuckles as Abigail grabs him by the collar and strums her lips near his face.

Following doctor’s orders or breaking the law

The next year — the 2014–15 school year — Abigail was preparing to enter fifth grade when the family was told that Sandlick lacked space to give her a room of her own. She couldn’t sit with the general population and was the only student at the school with such severe needs, Randy said. The district moved her to a self-contained classroom at Longs Fork Elementary School in Clintwood.

The new school put her in a desk that was too small — for “2- and 3-year-olds,” Randy muttered. Her parents watched her regress — more outbursts, biting, pants-soiling, repetitively smelling people, not sleeping for several nights — even as teacher annotations in her IEP documented a smooth transition to Longs Fork along with academic progress.

Entering sixth grade in the fall of 2015, she was moved yet again, this time to Dickenson County’s most spectacular building, a new $110 million Clintwood campus that consolidated the middle and high schools. Randy was unhappy even before school started, criticizing the new school for promising, but not delivering, the extra supports that Abigail needed to deal with transitions, including several acclimatizing pre-visits.

Abigail attended Ridgeview Middle School for about three weeks: Her anxiety, diarrhea, and biting outbursts spiked. Randy complained that she had been given a first-year special education teacher and a first-year speech therapist, neither with autism training. With doctors recommending that she leave the school, the Looneys pulled Abigail out — for the district, it was a violation of truancy laws.

Randy began calling attorneys, several of whom said his mountain community was too far away. Months later, a lawyer from another part of the state recommended that they call Janet Lennon.

A seasoned advocate arrives

Sharp, forceful and fashionably blingy, Lennon was prepared for a jury trial, not an IEP meeting in a drab school conference room. A former stay-at-home mom in New Jersey, she guided families in the struggle to win better placements in a few dozen districts across the Northeast.

The Looneys were like most of these clients: parents whose lives had been taken over by advocacy for their children and whose homes doubled as command centers, with boxes of files tabbed by bright Post-its in cluttered kitchens and family rooms.

Parents who seek Lennon out have been in conflict with their school districts for at least three years, she said, “if not six.”

Lennon’s challenges in placing her own disabled child compelled her to support others — a common trajectory for professionals in the world of autism. She created a support group before expanding into full-time consultancy.

“That’s how I cut my teeth in the industry,” she said. “Then I realized I kind of have a thing with memorizing law.”

With the experienced, no-nonsense strategist directing the action, the Looneys felt energized in the pursuit of a private placement.

They took several actions: filing a formal complaint with the Virginia Department of Education, pressing for mediation and seeking a due process hearing.

Their goal was to force the district to meet with them. They continued trying to informally persuade Ridgeview to make changes that would allow Abigail to return.

Eventually, a meeting was scheduled in October 2015; a dozen Dickenson County representatives were present. Because Lennon was there, the district delayed the meeting until it could reach Patrick Andriano, an attorney with Reed Smith — a 1,700-lawyer firm that handles special education disputes across Virginia and other states.

The Looneys expressed disbelief that school officials would spend thousands of dollars fighting a better placement for their daughter while facing a $1.7 million budget cut that had forced them to lay off 42 staff members. In all, district funding had decreased by nearly $6 million since 2009, with 99 staff positions cut.

But the shortfall also made what could be an annual six-figure private placement for Abigail less tenable.

Lennon argued that the school’s IEP goals, many of which had been repeated over time, weren’t sufficiently measurable; Abigail, she noted, had been working on writing her first name “with fair legibility” for at least three years.

When Lennon pointed out that specialized services didn’t exist in the area, school officials agreed there was nothing. That’s why they worked so hard to maintain services in the county’s schools, they said, and were gratified that they had helped Abigail make “substantial gains.”

When the family asked to see records of her gains, however, the file contained only two hand-notated pages from second grade.

“My concern, when I look at the years and years of intensive intervention that you all have invested,” Lennon said, “is that Abigail has minimal, if any, coping skills in transitional changes, and she doesn’t have a communication method in which to express it.”

Janet Lennon works with families across the Northeast who are at odds with school officials over special education services. Most of her clients, she said, have been battling the system for years.

The family wanted to place Abigail in an alternative setting with intensive applied behavioral analysis (ABA) therapy — the most widely accepted treatment for these and other autism-related impairments, which uses data, repetition and positive reinforcement to teach basic skills and more complex interactions.

The district demurred, saying that Abigail’s problems stemmed from her persistent absence from school.

“At this point we think, in our public school setting, we can serve her needs,” a district representative said. “We have in the past, we’re committed to doing that, and we would like to get her back into school.”

Lennon asked about the school’s ability to provide ABA therapy; a certified behavior analyst on contract with the district said she was training staff in the approach. Glennis pointed out that this woman was in Dickenson County about twice a month; certified behavior analysts worked every day at a private school she visited.

In an October 2015 letter to school officials provided to The 74, Abigail’s doctor Gayle Bates highlighted problems that stemmed from inconsistent special education services since she transitioned to Longs Fork in 2014.

“[Abigail] would be most appropriately treated with intensive ABA provided by a certified ABA therapist,” concluded Bates, a pediatrician in Bristol. “It is my recommendation that she be placed in a private autism school that can meet her significant educational and behavioral needs.”

University of Virginia pediatrics professor Dr. Kenneth Norwood, chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Children With Disabilities, was more blunt.

“Abigail will soon be a candidate for a residential placement if intensive interventions are not instituted,” he wrote. “It has become clear that even her basic needs cannot be met appropriately in a public school environment.”

Norwood’s letter went on to describe an educational setting that he believed would be commensurate with Abigail’s needs. It was a world away from anything she had ever encountered, with an experienced staff trained to work with children suffering from severe autism, development of a method of communication that she could use to effectively convey her needs, an appropriate sensory diet (activities that build attention and responsiveness) and at least 25 hours per week of intensive ABA therapy. All of these supports, he continued, should be analyzed by a behavior analyst daily.

District officials held fast. They denied Glennis and Randy’s request for home instruction because Abigail was physically able to attend class. And Abigail’s absences remained unexcused.

“If your child continues to be absent without a valid excuse, both the parent and child may be subject to juvenile court proceedings,” John Whitner, Ridgeview Middle School’s principal, wrote in a November letter.

A way out, but school won’t let her go

Two months later, the family faced a truancy officer at the school board office, but Abigail’s screaming overwhelmed the conversation. She also attacked her mother physically several times.

Lennon, as usual, stepped forward, saying of Abigail, “Even though we were providing medical documentation every two weeks of her self-injurious behaviors and her emotional-behavioral deterioration, the reason for denial was that the family was willfully withholding her from school, which is absolutely, obviously not the case.”

April Collins, a probation officer who attended the truancy meeting, later said she had never met a child with such severe autism, noting that Abigail was wearing pads on her forearms “like a football player.”

Rather than finding against the Looneys, Collins suggested they apply for funds from a pool of state and local money set aside for at-risk youth. The fund’s stakeholders voted unanimously to pay for Abigail’s private placement.

In order to receive the money, though, Ridgeview had to state in Abigail’s IEP that the placement was for educational reasons, which it refused to do.

It added that private placements were generally made within the same county in deference to IDEA’s least-restrictive-environment provision (though there wasn’t an appropriate private school in the county). The Looneys hoped for a school in Lynchburg, several hours away.

“Yes, a public school probably cannot compete with a private school in terms of what they’re doing, and you can argue that point,” Whitner, the Ridgeview principal, had stated at the IEP meeting. “But I on the other hand believe that we can provide her, and we want her back, and we want to be able to show what we can do.”

“Why?” Lennon asked. “Is she a litmus test for you?”

Student artwork lines the hallways at the Blue Ridge Autism and Achievement Center in Roanoke. The private school was designed to serve disabled students who struggle in typical environments.

Blue Ridge: no more dreaded phone calls

From sunset to sunrise, Abigail didn’t stop screaming. The family was spending the night at a hotel in Roanoke, and the phone was ringing off the hook. Other guests were complaining.

“What’s going on over there?” Randy recalled hotel staff asking. “Do we need to call 911?”

The next morning, Randy and Glennis drove their daughter to the Blue Ridge Autism and Achievement Center, a private day school that specializes in intensive autism care. For years, Randy said guiltily, he didn’t know such a place even existed.

“It was amazing,” he said. “I was beholding children who were as autistic as our daughter, sitting, learning, communicating, and I said, ‘What have I done? I let six years go by, I let six years of my daughter’s life go by, and I could have had her here.’”

Staffing at Blue Ridge can’t be rivaled by public schools. At the Roanoke campus, 68 staff members serve 60 students. The staff includes nine certified behavior analysts, who monitor each classroom and collect student performance data each day. And while Virginia’s schools refer a higher rate of disabled students (and all students) to law enforcement than any other state, Blue Ridge rarely punishes students, said its executive director, Christina Giuliano.

The school’s ability to handle difficult situations makes an enormous difference for parents.

“For the first time, a lot of these parents can drop their kids off and go to the grocery store and be like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’ve never been able to do this. I’m not worried about whether I’m getting a phone call to come pick my kid up,’” said Angie Leonard, the school’s founder.

Marcus Mnich, who has autism and Down syndrome, makes breakfast at the Blue Ridge Autism and Achievement Center in Roanoke, as Ryon Birtsch, a behavior technician, takes notes.

Ellen Mnich remembers the dreaded phone calls well. For over a year, school officials in Botetourt County, in the hills north of Roanoke, would call her, almost daily, to pick up her 17-year-old son Marcus, who has autism and Down syndrome. On other days, the bus would drop him and his disabled classmates off before the school day had even ended.

He began to place his parents in a “police hold,” a restraining technique the Mnichs feared he learned in school.

Like the Looneys 200 miles west, the Mnich family asked for a private placement after observing what they considered a pattern of inadequate instruction and mistreatment. Lord Botetourt High School argued that Marcus was meeting his IEP goals.

Her allegations, Ellen Mnich believes, led the school to retaliate. Marcus sometimes had difficulty using the bathroom on his own. He was susceptible to painful skin rashes — a symptom of prediabetes — and had suffered burns from improperly cleaned diarrhea.

She asked school officials to rinse out his underwear (“don’t send the whole bowel movements home”) and then found feces placed in specimen bags in Marcus’s backpack three times in two weeks, the last time inside “a half a gallon of diarrhea toilet water.”

Furious, the Mnichs said, they drove to district offices and pulled out the bag in front of the superintendent at the time, Tony Brads. “Don’t you dare put that on my desk,” they recalled him responding.

Unsurprisingly, the visit wasn’t productive. Brads wanted to go to his daughter’s soccer game. “Is this what is so important that you had to meet me on a Friday afternoon?” the parents said he demanded to know. Brads told them it wasn’t his staff’s job to clean Marcus’s laundry.

The Mnichs took their story to the school board, and this time they had an advantage: Reporters were covering the meeting and picked up Marcus’s story. Botetourt school officials subsequently agreed in June 2015 to provide Marcus with a private placement at Blue Ridge — an agreement Ellen attributed to media scrutiny.

Another Botetourt County student, Devin Bailey, secured a private placement at Blue Ridge’s Lynchburg campus after he came home from his local school with unexplained bruises on his face. Also in Botetourt County, Roxanne LaPradd said Lennon helped win a place at Blue Ridge for her son Dale, who has severe autism and repeated his same IEP goals — unmet — for five years. He is 20.

Brads has since left the district. John Busher, the current Botetourt superintendent, declined to comment about individual student cases, citing federal student privacy law. He noted, however, that the U.S. Department of Education’s 2016 IDEA report cards placed Virginia among 23 states and territories that met federal compliance requirements for special education.

“We believe that our school division has contributed to these high marks,” Busher said in an email.

The Mniches said their son Marcus has made drastic improvements since he enrolled at Blue Ridge. With hearing assistance — an impairment the family said Botetourt failed to evaluate — he no longer sits directly in front of the television with the sound blaring. He’s no longer aggressive, said Ellen, and he doesn’t refuse to go to school.

At Blue Ridge, behavior technicians carry binders to chart how students perform on each task. At the end of the day, they add the data to a graph measuring progress in different areas and calibrate the next day’s activities.

Students get a reward after each activity. For Marcus, that meant an opportunity to play on an iPad. To finish one morning’s task, making himself breakfast, he chugged a bottle of milk to get to his reward.

“Hey, take it easy,” said Ryon Birtsch, the behavior technician. “Take a deep breath.”

Glennis watches as her daughter Abigail plays with an iPad.

A settlement but an uncertain future

In a strip mall parking lot, Lennon sat in her dark blue Nissan Altima talking on her cell phone. The car’s dashboard was covered with sticky notes, Tic Tacs and beef jerky were stashed in the center console, and bankers boxes of documents were piled in back.

On the other end of the call was LaRana Owens, one of the Reed Smith attorneys representing Dickenson County.

After months of back-and-forth between lawyers, advocates, parents, doctors, school district officials, education department officials and a third-party mediator, the Looneys and the county reached a settlement on May 19. Reed Smith representatives didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In that document, which the Looneys provided to The 74 before it was signed, the county denied wrongdoing while agreeing to Abigail’s placement at the Blue Ridge campus in Lynchburg. The district agreed to pay the parents $16 per day for transportation costs, according to the settlement. Abigail’s tuition costs would be paid for through the state’s Children’s Services Act fund. The parents agreed to absorb all other expenses, including rent for an apartment near Lynchburg, where they will live during the week.

Randy and Glennis didn’t know for sure whether the program at Blue Ridge would be right for their daughter, but they were grateful that she was given a chance to try.

They were grateful for the chance to see whether Abigail’s potential can still be found, but time is ticking. The agreement with the school district guarantees Abigail’s placement only through the end of the 2017–18 school year. After that, her education is uncertain.

She will be 14 years old.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)