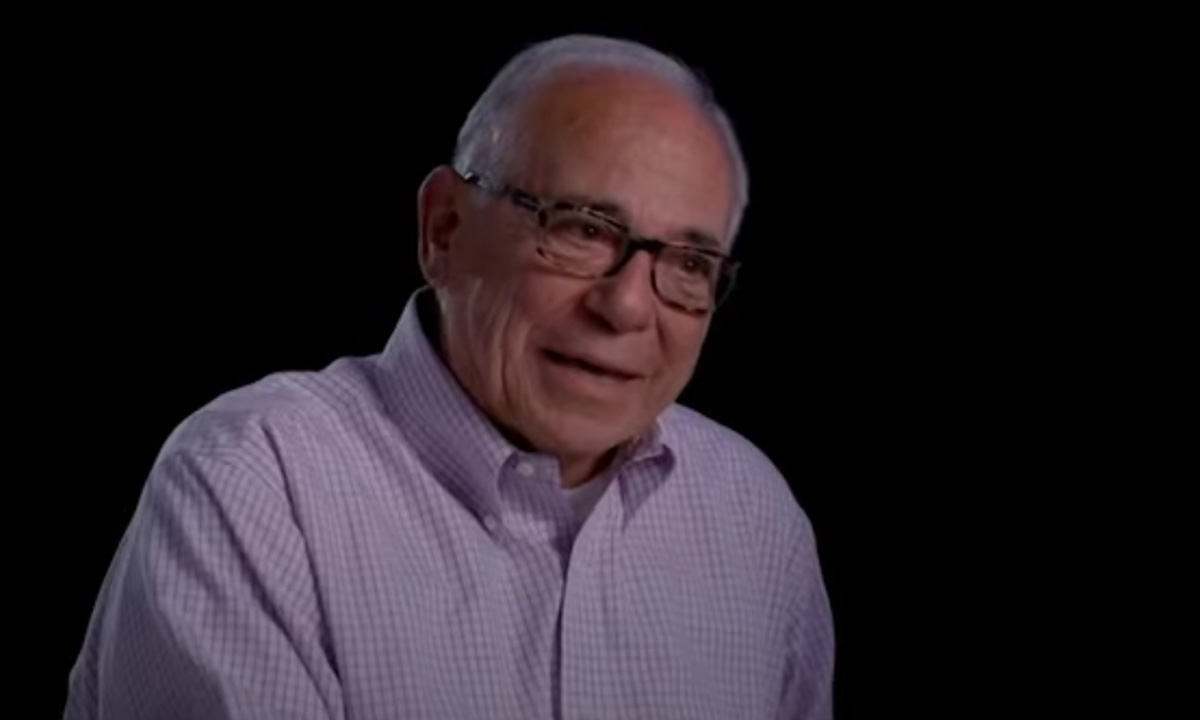

An Appreciation: How Don Shalvey Shaped the Charter School Movement

Freedberg: In California and beyond, this pioneer helped make charters a significant part of the education system over the last three decades.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated

Don Shalvey died March 16, 2024, of glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. He was 79.

A compelling case could be made that without Don Shalvey, the charter school sector would not have grown as rapidly into the vibrant movement it is today, serving 3.7 million students in nearly 8,000 schools across the United States.

Much of what Shalvey accomplished was based on his emphasis on building relationships and networks — and his exuberant personality, now tempered by brain cancer first diagnosed in December 2022. He has been vigorously fighting glioblastoma with the same fortitude that made him a pioneer in entrenching charters as a significant part of the nation’s education system over the last three decades.

As superintendent of a small district south of San Francisco, Shalvey opened the San Carlos Learning Center in 1994. Now called San Carlos Charter, it was the first charter school in California and just the second in the nation, after City Academy in St. Paul.

Partnering with a pre-Netflix thirtysomething named Reed Hastings, Shalvey was instrumental in getting a legislative cap of a mere 100 charter schools for the entire state lifted — and replacing it with a limit of 100 per year.

Today, despite intense opposition from the California Teachers Association, the state now has over 1,300 charter schools. One-fifth of all charter school students in the United States live in California, a disproportionately large number relative to the state’s population.

Shalvey and Hastings also came up with the idea of creating a nonprofit organization to run several charter schools simultaneously, and getting it written into law. Using that authority, they co-founded Aspire Public Schools, the nation’s first charter management organization.

Today Aspire, with 36 schools, is one of the most esteemed CMOs in the nation. And one-third of all charter schools are run by a CMO.

Shalvey expanded his work on behalf of charter schools nationally as deputy director of K-12 programs at the Gates Foundation. During his time there, charter enrollments grew by a half-million as a result of support from the Charter School Growth Fund underwritten by Gates and other foundations. But his efforts extended far beyond just charters, especially in implementing the Common Core standards and improving teacher preparation in several states.

Most recently, as CEO of San Joaquin A+, he has focused on improving outcomes for mostly Latino students in his beloved San Joaquin Valley. He has lived there for the last two decades, on a ranch in a small town near Stockton, with his wife, Sue Shalvey — herself a teacher, principal and leader in special education.

But his roots were in Philadelphia, where, by his own account, he learned lessons that shaped everything he did — including finding the right people to work with which to accomplish the seemingly impossible.

“I grew up always wanting to be around people who were better than me in things I was trying to be good at,” Shalvey said in a recent interview. For example, to improve his skills on the basketball court, “you rounded up a team of your friends, and go to the toughest place you find in Philly to get better.”

Shalvey “is the living embodiment of Philadelphia street smarts and California dreaming, all in the service of students and their families,” said Bob Hughes, Gates’s director K-12 education in the U.S. “His intelligence, joy and exuberance light up every room he enters. ‘Protean talent’ is an understatement. Don would visit a classroom in the morning, meet with a group of principals in the afternoon and catch a jazz concert in the evening. And you would rush to keep up.”

Founding the San Carlos Charter, “took a lot of courage that you don’t see in too many school superintendents these days,” said Eric Premack, executive director of the Charter Schools Development Center, a support and advocacy organization.

Starting Aspire, said Premack, who has worked alongside Shalvey since those early years, was “another groundbreaking thing to do, a gutsy move for a traditional school superintendent to make.”

I first met Shalvey over two decades ago, when, as an editorial board member at the San Francisco Chronicle — and charter school skeptic — I wrote a long and supportive piece about the just-opened Lionel Wilson Prep High School, in one of Oakland’s roughest neighborhoods.

The park across the street had been chained shut for years because it was a haven for drug dealers and violence. The school, named for Oakland’s first black mayor and sporting gleaming corrugated aluminum panels, purple stucco walls and yellow doors, beamed hope into its struggling neighborhood.

It had been the first public school to open in Oakland in over 20 years, made possible by an $18 million private bond measure floated by Aspire.

An indication of Shalvey’s ability to bridge hostile divides, or even chasms, is that he persuaded then-Oakland superintendent Dennis Chaconas to join the school’s board of directors.

I did not see Shalvey for nearly a decade after that — until I became director of EdSource, and he was on its board. He enthusiastically supported its transformation into a journalism organization covering education in California.

Shalvey’s partnership with Hastings was crucial to some of his most public successes. To force California to raise the charter cap again, as the 100-school maximum had already been reached by 2005, they gathered the more than 1 million signatures needed to put an initiative on the ballot.

“The [teachers union] said, ‘We don’t necessarily like what you are doing, but we don’t want to spend the money to defeat you at the ballot box,’ ” Shalvey said. And then, in classic Shalvey style, he reached a compromise on the legislation so the union didn’t oppose it.

“The combination of Don as Mr. Charming Establishment and me as a wealthy provocateur presented a unique challenge to the teachers union,” Hastings recalls.

Carl Cohn, a leading educator who served on the California State Board of Education, recalled that when he was superintendent in Long Beach and Shalvey was in San Carlos, they backed the state’s original charter law. “Both of us thought that reducing bureaucracy and bringing teachers and parents closer together in the design of classroom programs that would benefit all kids was a really good idea. We were both heading traditional districts at the time. Unlike me, Don has stuck with that really good idea throughout his career of more than half a century.”

“As we look at the emerging polarization and culture wars taking place in K-12 education today,” added Cohn, pointing to perhaps Shalvey’s greatest contribution, “Don’s calming voice resonates with both sides and is needed now more than ever.”

In addition to his humor and resolve, Shalvey brought an entrepreneurial spirit to his work. “A good way to spot an entrepreneur is that they don’t think they are taking risks,” said Hastings. “They just plunge in, they know how to win, they know how to make a difference.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)