Amid Literacy Push, Many States Still Don’t Prepare Teachers for Success, Report Finds

Too many states aren’t giving teachers the skills to teach reading effectively, according to an analysis by the National Center on Teacher Quality.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Most states have revised their strategies for teaching children to read over the last half-decade, a reflection of both long-held frustration with slow academic progress and newer concerns around COVID-related learning loss. An attempt to incorporate evidence-based insights into everyday school practice, the nationwide campaign has been touted as a promising development for student achievement.

But many states don’t adequately train or help teachers to carry out those ambitious plans, according to a new analysis.

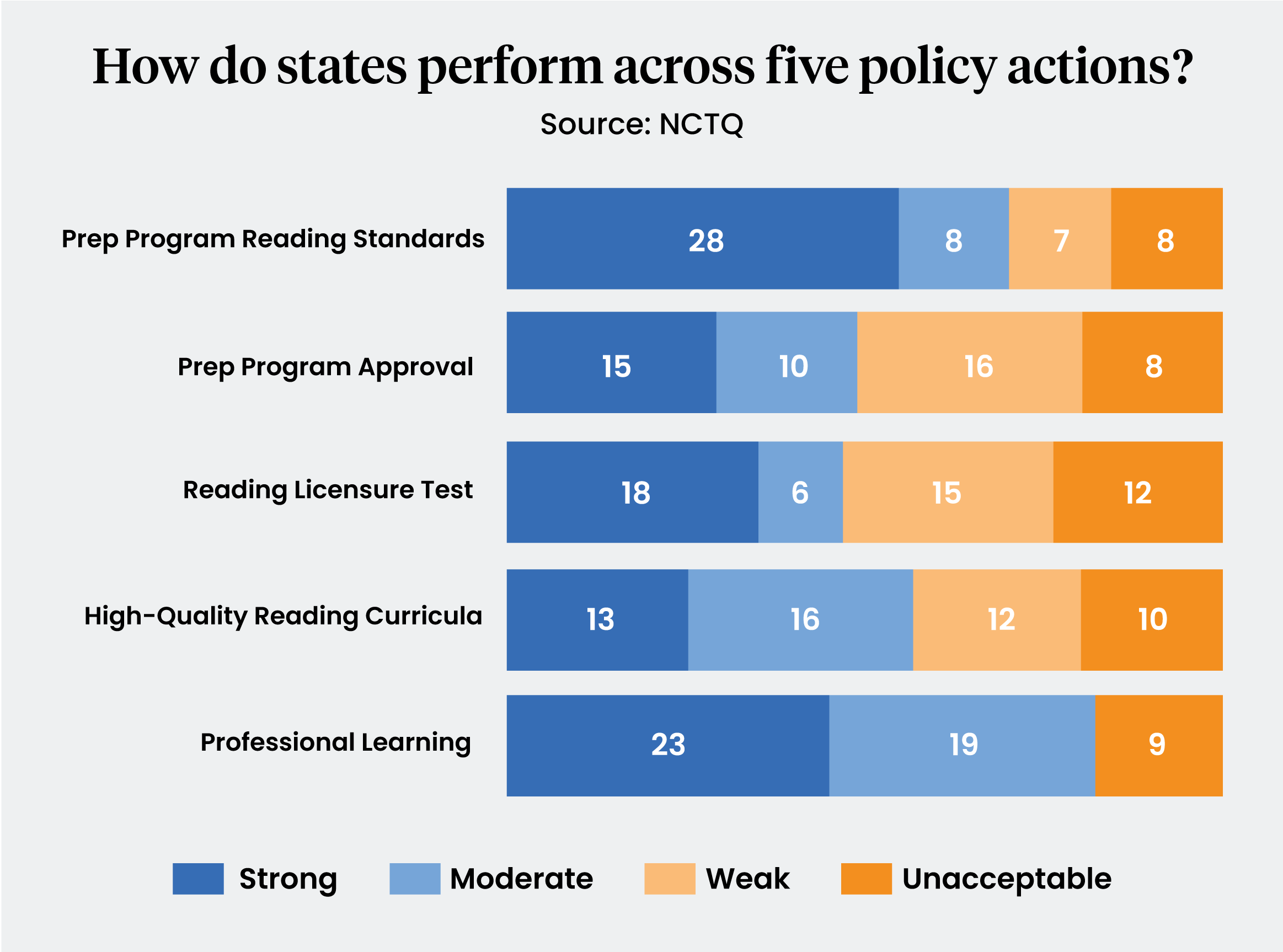

The report, released today by the nonprofit National Center on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), identifies five key areas where education authorities can arm teachers with better skills to teach the fundamentals of literacy — from establishing strict training and licensure standards for trainees to funding meaningful professional development to classroom veterans. While a handful of states were singled out for praise, others were criticized for inaction or half-measures.

Dozens of states use licensure tests with little or no content related to the “science of reading,” the extensive body of research into how people understand written language (including one, Iowa, that administers no licensure test that deals with reading whatsoever.) The vast majority do not require districts to choose reading curricula that reflect the science of reading.

NCTQ President Heather Peske, a former high-ranking K–12 official in Massachusetts, applauded recent changes in state law as “well-intentioned,” but cautioned that they could only meet with success if executed with care.

“Passing state policy is the very beginning stage of doing this work,” Peske said. “It’s really the implementation that we need to focus on now.”

Though it has germinated in academic and policy circles for years, the legislative push around early literacy first gained public prominence in Mississippi, which enacted a rash of new laws around reading instruction a decade ago. That dramatic overhaul included changes to public pre-K offerings, new resources provided to districts (including special coaches assigned to underperforming schools), and even the controversial practice of holding back third graders who failed an end-of-year exam.

Mississippi was identified in the report as one of the national leaders implementing necessary reading reforms, along with Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, Minnesota, Ohio, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Virginia. By contrast, Maine, Montana, and South Dakota were rated “unacceptable” across the five recommended action items.

Even as aspiring teachers are being trained, the authors argue, many are being set up to fall short in their first assignments. Just 26 states provide detailed standards for what teaching candidates need to know about the science of reading, including critical aspects like phonics, phonemic awareness, and fluency. Twenty-one states don’t establish any standards for the specific instruction of English learners, who account for as much as 20 percent of all K–12 students in places like Texas.

In spite of the clear signs that thousands of teachers are minted each year with incomplete or inaccurate notions of the science of reading, a majority of state education departments allow outside entities and accreditors to approve literacy offerings in schools of education and other teacher preparation programs. Just 23 states administer their own process of approval, and only 10 consult literacy experts in the decision of whether to approve individual programs.

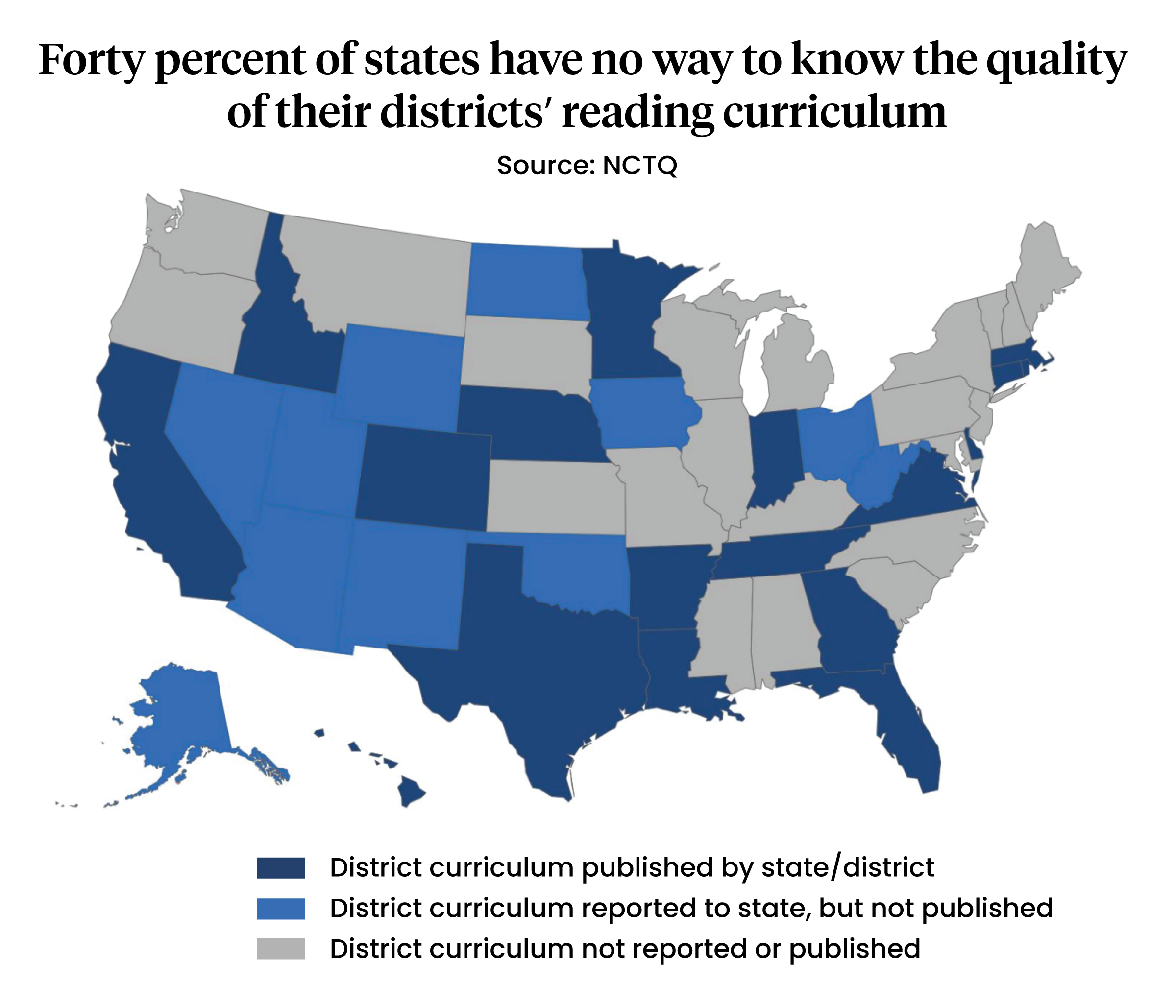

Once those new teachers enter the classroom, many will be stuck using materials that are poorly aligned with the best research on how to improve reading outcomes, the study concludes. Only nine states — Nevada, Arkansas, Tennessee, Connecticut, Delaware, Rhode Island, Ohio, Virginia, and South Carolina — require that districts use high-quality reading curricula, such as those approved by vetting organizations like EdReports. The remaining states, accounting for 40 million K–12 students, make no such requirement; 20 states don’t even collect data on which curricula districts are using, so families must make their own inquiries into whether their children have access to effective instruction.

Even while popular early literacy approaches, such as “guided reading” and “balanced literacy,” have fallen out of favor with education experts in recent years, hundreds of school districts still spend millions of dollars each year to access them. Some include wealthy suburban districts in high-achieving areas like Greater Boston, where high average reading scores are complicated by large disparities between high- and low-performing students.

Peske said that while the report did not delve into regulatory questions like whether to introduce universal dyslexia screening or to retain low-scoring elementary students for extra reading instruction, those issues were also important parts of state rules around foundational literacy. But teacher preparation and support stood above the rest, she concluded.

“We know teachers matter most; they’re the most important in-school factor in impacting student outcomes,” she said. “So if we’re actually going to see improvement in student reading rates, we need to make sure teachers are prepared and supported to implement and sustain scientifically based reading instruction.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)