Amid Fierce Debate About Integrating New York City Schools, a Diverse-by-Design Brooklyn Charter Offers a Model

Outside Brooklyn Prospect Charter School’s Windsor Terrace campus, a river of middle schoolers are attempting to beat the morning bell. As the kids stream in, each gets a fist bump and eye contact from Principal-in-Residence Kiersten Gibson-Cooper. The line momentarily bunches up as students swipe their badges at a front desk, but once past the bottleneck, the teens are remarkably quiet as they disappear into classrooms.

Watching the morning routine, you’d never know the school is located at the epicenter of one of the nation’s most fiercely joined integration debates. In contrast to the diversity of students’ races, ethnicities, incomes, disability statuses and home languages evident in the Windsor Terrace halls, schools in the surrounding district, New York City’s Community School District 15, have been intensely segregated, mirroring the city as a whole. District 15, though, is implementing an integration plan that has disrupted the way students are assigned to schools — and diverse-by-design Windsor Terrace, a public charter school that is inside the district but not part of it, might provide a road map for success.

(A separate, parallel process involving two proposals to address segregation and overcrowding in the district’s elementary schools was recently put on hold because of concerns that low-income families were not adequately engaged.)

“We are very excited District 15 is going down this path,” says Brooklyn Prospect co-founder Daniel Rubenstein. “Enrolling a diverse student body is step one. The harder work is having a diverse and successful program…. How do you seed and make that a fully integrated community where equity and inclusion is really woven into the fabric of the community?”

Last year, when Richard Carranza took over as schools chancellor for New York City’s 1.1 million public school students, he made integration a priority in the nation’s largest district. In August, a panel appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio recommended doing away with the criteria that most city schools use to screen students. A decision is likely months away.

Meanwhile, a large swath of the community in District 15, which is home to both working-class immigrant neighborhoods and wealthy enclaves like Park Slope, was lobbying the city for permission to attempt to integrate its middle schools.

This year, the district’s middle schools did not use test scores or other selective-admissions screens to admit students — a practice that has reinforced segregation — but instead filled their classrooms using a lottery weighted to ensure socioeconomic diversity.

That’s exactly the model used at Windsor Terrace, which was opened in part to demonstrate that an individual school could enroll, and succeed with, an integrated student body. Kids are admitted without regard to their academic or behavioral histories via a lottery that gives preference to district residents and economically disadvantaged students. Half the student body at Windsor Terrace is low-income, about the same percentage as the district.

What happens in District 15, then, may help shape future enrollment policies citywide. Because the district and the Brooklyn Prospect charter school network use essentially the same system for admitting students, advocates suggest that the New York City Department of Education could ask local district and charter school leaders to pilot the kind of unified enrollment system that has made school assignments more equitable in cities such as Washington, D.C., Denver and New Orleans. District and charter school leaders would have to set aside their mistrust, give students a single application on which to rank their preferences and allow an algorithm to assign them to open seats in both types of schools.

Asked whether a unified enrollment system that includes both district and public charter schools is under consideration, the city Department of Education had no comment.

More immediately, as discussions about desegregating schools in other parts of New York take place, integration advocates hope parents and policymakers in District 15 and throughout the city will consider not just Brooklyn Prospect’s process for getting a cross section of students into its buildings, but also how the four schools in the 10-year-old network foster a culture of equity and inclusion. If District 15’s newly integrated schools want to avoid tracking by academic level and other practices that segregate students within ostensibly integrated buildings, there’s plenty more work to be done.

“You have to create a community where people of color can bring their whole selves,” says Rubenstein. “There isn’t one 100 percent solution. It’s more like 10, 10 percent solutions.”

To that end, the adults in the small school network spend lots of time thinking about how to make sure groups of children with differing needs and backgrounds can succeed in the same classroom. From the art on the walls to the materials on student desks, every detail is planned through that lens.

“We knew that creating a strong program that had community buy-in was incredibly important,” says Rubenstein. “You need to create a school that all families will find attractive. You need to make sure there’s no false choice between a diverse school and one that’s right for their child.”

According to Brooklyn Prospect, in the 2019-20 school year, 41 percent of Windsor Terrace’s 324 middle schoolers are white, and 34 percent are Latino. Black students comprise 11 percent of enrollment, and Asian students, 6 percent. Half are economically disadvantaged, and 25 percent receive special education services.

Diversity varies among Brooklyn Prospect’s four schools. Of students at the K-8 Downtown campus in 2017-18, for example, 38 percent were white, 32 percent black and 15 percent Latino. At the network’s high school, 40 percent of students were Latino, 33 percent white and 13 percent black. At Clinton Hill Middle School, 36 percent of students this year are white, 35 percent black and 15 percent Latino, and 35 percent qualify for free or subsidized lunch.

In 2018, Windsor Terrace was in the 89th percentile of academic achievement citywide in reading and in the 91st percentile in math. Test scores, which dramatically outpace city averages, have risen steadily over the past five years. Schoolwide reading scores have risen from 43 percent of students proficient in 2015 to 69 percent in 2018. In math, scores jumped from 53 percent to 69 percent proficient.

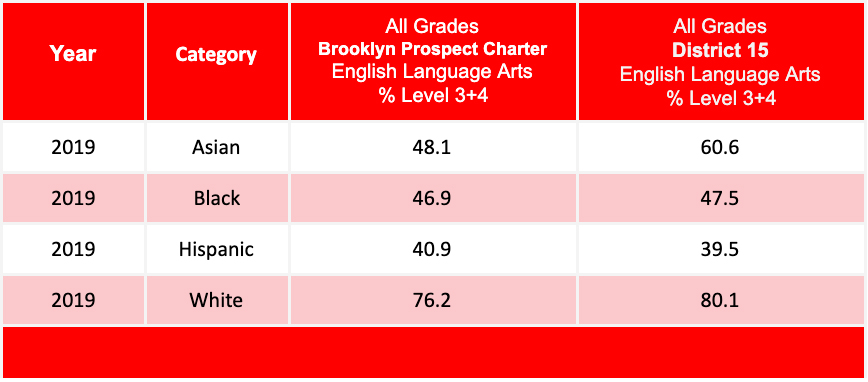

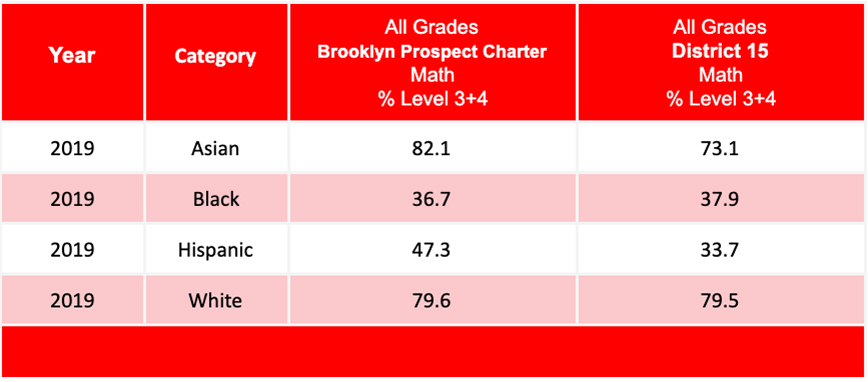

As in District 15 schools, there are racial gaps in Windsor Terrace students’ reading and math proficiency. Students perform comparably, except for Latino and Asian kids outperforming their district peers in math and Asian students lagging in reading.

Brooklyn Prospect Charter vs. District 15 (English Language Arts)

Brooklyn Prospect Charter vs. District 15 (Math)

Team teaching and real-world relevance

In preparing for the school’s opening in 2009, Rubenstein and co-founder Luyen Chou hired teachers from diverse backgrounds and with demonstrated track records of success. Today, more than half of the educators in the network’s schools are people of color, and every adult participates in regular equity and inclusion training.

The next step was to ensure that those teachers helmed classrooms that were themselves integrated. While many high-poverty schools cluster students with particular needs in the same classrooms — either because specific teachers are better at behavior management or to facilitate grouping kids by ability — Windsor Terrace, like the other Brooklyn Prospect schools, desires a representative mix in each class. In addition to balancing students’ races and ethnicities, educators take into account their fluency in English, gender, gender identity and sexual orientation.

Then, because of the array of student needs in each class, Windsor Terrace puts two teachers in most rooms. Usually, this means one is the expert in the subject being taught and the other a teacher of special education or of English learners. This allows staff to work with students who are at different levels of academic mastery and need individual help with behavior or disability accommodations.

As often as they can, teachers plan lessons that have ties to students’ lives. During September’s United Nations Climate Action Summit, for example, Windsor Terrace students were permitted to leave school to attend protests. Most chose to stay in Brooklyn, instead marching around the school and engaging in related projects. For eighth-grader Mia Zaborski, the daughter of Canadian immigrants who live near the sought-after Cobble Hill neighborhood, that included an art class unit on designing substitutes for single-use plastics. Several of her classes wrap projects involving climate change into the curriculum.

In many schools, classes organized around this kind of real-world engagement are reserved for the most advanced students. But Brooklyn Prospect teachers are careful to extend the strategy to everyone. A teacher of both special education and science, Ava Kerr prepared lessons on carbon dioxide emissions from the 1850s to the present.

“It’s so much anguish and existential dread,” she says. “So I’m trying to channel that into positive action.”

She puts each day’s lesson into a Google document, where she breaks down ways it might be modified for three groups of students: kids with special education plans, those who are behind and those who are likely to master the material quickly and need what the school calls seeker opportunities — more advanced projects to keep them engaged and deepen their understanding. Because she is mentoring a special education teacher resident from the Relay Graduate School of Education, Kerr writes a section titled “why” for every adjustment she suggests.

Windsor Terrace doesn’t get any additional funding, public or private, to pay for its co-teaching model. The number of teachers on staff is the same as it would be if students with disabilities and English learners were served in discrete classrooms apart from their peers.

On a recent morning, for example, humanities teacher Craig Redmond Cilley and special education teacher Michael Marsigliano are moving quietly among small groups of sixth-graders who are researching Mesopotamia. While Marsigliano helps one group unpack the concepts of justice in the Code of Hammurabi, Redmond Cilley returns several times to the side of a boy who is quiet but turned away from the group and clearly upset.

The student had an altercation with a classmate, Redmond Cilley explains later, and was having a hard time calming down enough to focus on the lesson. The teacher knew the boy well enough to understand that a quick break across the hall, where Windsor Terrace’s counselors sit, would give him a moment to regroup. While the boy was gone, Redmond Cilley spoke with the other student involved in the incident so both would be heard.

If the episode had been more serious or lasted longer, he might have been asked to participate with Redmond Cilley in a collaborative problem-solving process. Windsor Terrace has times scheduled during the day for individual teachers and students to work out plans for better behavior together, says Director of School Culture Dwight Thomas.

“A teacher may say, ‘You’re talking out of turn a lot,’” Thomas explains. “And the student may say, ‘But I’m bored.’” Fixing boredom, he continues, is more effective than meting out punishment for talking.

Redmond Cilley was able to head off a major disruption in his classroom, Thomas says, because he knows his students well enough to understand what the student who was most upset needed and because he was quick to welcome the boy back into class.

‘Embedded honors’ and student risk-taking

Likely oblivious to all this, student tour guide Mostafa Al-Garadi, peering into the classroom, says Redmond Cilley is his favorite teacher so far. The son of Yemeni immigrants, Mostafa is a seventh-grader. He took Redmond Cilley’s class last year and remembers well the Mesopotamia lessons. In a few weeks, he explains, the class will study similar aspects of the Roman Empire and then more recent civilizations.

Down the hall, he stops in front of a display detailing fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad’s rise as the first Muslim American woman to wear a hijab and win a medal while competing on a U.S. Olympic team. A native of New Jersey, she was part of a team that brought home a bronze medal in saber in 2016.

“A lot of people learned a lot from her,” Mostafa says. “She was one step toward more inclusive because Muslims are often portrayed as terrorists, especially after 9/11.”

The network’s first few years, Brooklyn Prospect enrolled diverse classes by recruiting in a variety of communities. In 2013, the charter school network got permission from its authorizer, the State University of New York, to experiment with a lottery that gives socioeconomic preferences to certain students. The state law requiring charter schools to admit by blind lottery had been changed in 2010 to allow weights for disadvantaged students.

A senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a think tank that has invested considerable time in studying integration and inequality in education, Halley Potter is quick to laud one of Brooklyn Prospect’s particularly innovative high school strategies. Located on the same campus as Windsor Terrace middle school, the network’s high school is one of a small number that use “open honors” or “embedded honors” to increase the level of academic challenge in diverse classrooms.

Students of any ability can opt into the honors version of many classes, completing extra assignments in exchange for the higher, weighted grade-point averages that are prized by selective colleges. Because all students, regardless of honors status, learn the same materials in the same classroom, the strategy allows kids to attempt the more rigorous method and, if they find themselves falling behind, opt back out without having to change classes.

“Everyone takes the class together, so you still have group projects and conversations,” says Potter, who has produced several toolkits for schools that are interested in exploring “detracking” in diverse classrooms. “Schools that use it often see an increase in the number of students in honors because maybe it doesn’t seem so intimidating to try.”

Brooklyn, she adds, is home to many residents who value integration and pushed for the diverse-by-design enrollment system that District 15 just rolled out. Potter is hoping that, given a taste of success in integrating, the community might take a further step and explore using a single weighted lottery to assign students to both district-run and charter schools.

Since the District 15 lottery is not very different from Brooklyn Prospect’s, and because the area also has a number of other diverse-by-design charter schools, it would not be too complicated to try the kind of universal enrollment system that has allowed some cities to provide both school choice and equitable access to good schools.

“That’s part of what I think is so exciting about District 15 now, is it’s such a center for this,” says Potter. “That focus on diversity in both the district and the charter schools is unique.”

David Tipson, executive director of integration advocacy group New York Appleseed, notes that the charter schools’ request to change the lottery rules made it easier for District 15 to overcome bureaucratic resistance to a new district enrollment scheme.

“The department said, ‘No, it’s not constitutional,’” he recalls, describing the push by Appleseed and the community for a district exception to traditional enrollment methods. “If we hadn’t been able to say, ‘Look, charter schools are doing it right now,’ it would have been a lot harder.

“That was the breakthrough,” he continues. “It was the first time in a long time that the Department of Education had approved a plan that regulated who was admitted to a school on some basis other than test scores.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)