Allies Rally Behind Indiana NAACP’s Black Student Achievement Proposal

Group’s 15 strategies for improvement roundly praised, but advocates worry conservative state legislature might not commit to change

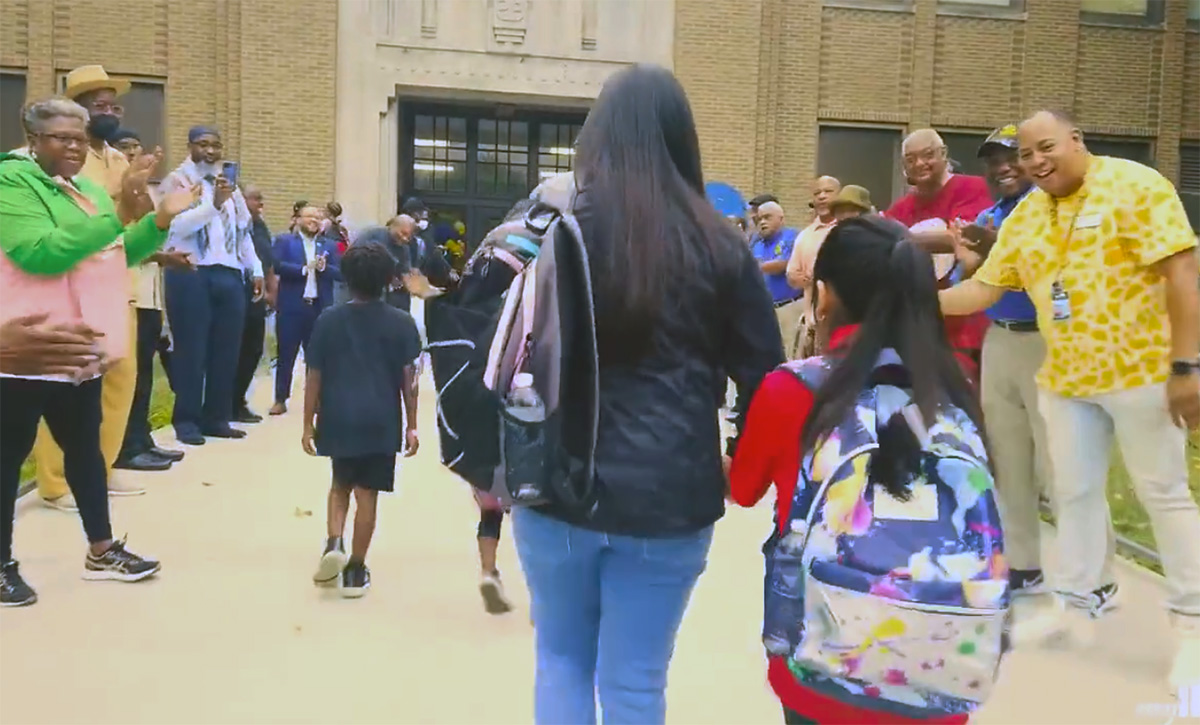

Four months after the NAACP State Conference released an aggressive plan to close deep and persistent gaps in Black student achievement — and with the state’s 1.12 million children returning to school — leaders in the civil rights group continue to build momentum around that road map.

The Indiana Black Academic Excellence plan, released in April, seeks to make Black student success a top priority for the governor and state education department. It also calls for equitable educational funding statewide and for the elimination of the digital divide, among a dozen other strategies.

It provides clear action steps in a state where Black students trail their white and Hispanic peers on virtually every educational measure, as evidenced by test scores out of the Indianapolis Public Schools: Last year, just 5% of Black 10th-graders in the district passed both the math and English sections of the state exams.

NAACP Education Committee member Carole Craig, who co-edited the report, said substantive change requires a new way of thinking about this group.

“First, we must agree that all Black children can succeed,” she told The 74. “If we don’t make a serious difference in the next couple of years, we are crippling the ability of this state to have a viable working class, to be a part of a global economy for all of its citizens.”

Most jobs require at least two years of education beyond high school, she said: Those who fail to graduate or pursue college will be unqualified.

Russ Skiba, professor emeritus at Indiana University, praised the NAACP’s proposal for its concrete answer to an educational crisis that has gone largely unaddressed for decades.

“What is so impressive about this plan is that it’s a blueprint,” said Skiba, former director of The Equity Project at Indiana University, which provides evidence-based information on school discipline, school violence, special education and education equality. “It says, essentially, that if we are serious about addressing the gaps in our schools, which grow into gaps in our society, make no mistake, then these are the things that need to happen.”

NAACP Education Chair Garry Holland said the report contains nothing new, that the data has been available for years.

So, too, he said, has the funding to bring positive change. What hasn’t materialized, at least not yet, is a concerted, sustained, statewide effort to improve these students’ educational experience.

“When you look at professional development, cultural competency, anti-bias training, does the school have the will to do these things and help these children?” he asked. “Money has been made available through ESSA (federal Every Student Succeeds Act) for that to happen. We know you have the resources. But do you have the will?”

Shawnta Barnes, an educational consultant who worked in Indianapolis Public Schools for three years ending in 2018, is among those trying to build that resolve. Barnes, who helped shape the NAACP’s plan, is now promoting it to local districts, presenting it not as a critique of their current practice, but as an opportunity to improve.

“Each of us has been assigned to different school districts and have been going out and having intimate conversations about it,” said Barnes, the mother of two boys enrolled in Washington Township Schools in Indianapolis. “We don’t want any school to feel we are attacking them. It’s more of, ‘This is our plan and how can we help you?’ We’re here to talk to schools, see if they are willing to work with us … and help them get grants and connect them with resources. We are a partner… and we will be down at the Statehouse fighting for the policies to be passed.”

The NAACP’s plan faces numerous hurdles, among them that Black students are spread throughout many districts, even within Indianapolis, meaning advocates will have to sell the proposal to each one.

Aleesia Johnson, superintendent of the Indianapolis Public Schools, the state’s largest, has already pledged to address the disparity. Her district, which serves 31,000 students, including those in charter schools, spent the 2021–22 school year designing a tiered support system for those campuses that have three consecutive semesters of “F” state-designated letter grades and are at the bottom of critical education metrics.

These schools overwhelmingly serve Black and Hispanic students.

In addition to expanding its tutoring program, her district has already partnered with two groups it hopes will improve student success: One is recognized for its anti-racist approach to learning and the other focuses on school district transformation.

“Unfortunately, the findings of the NAACP report on Black student achievement are not surprising,” Johnson said in a statement to The 74. “The results are all too common among school districts across the country.”

Looking to repeat anti-CRT victory

Though the NAACP’s plan faces numerous challenges, proponents take heart in an earlier, surprise win: The same coalition that managed to keep anti-critical race theory legislation off the books in Indiana earlier this year — including the Urban League, Equity Project, Indiana State Teachers Association and Indiana Black Legislative Caucus, among many others — also supports the NAACP’s plan.

Critical race theory, which examines how American racism has impacted a wide range of the country’s systems and institutions, has become a catch-all phrase made popular by conservative operatives and politicians trying to rally their base around issues of race. Many thought the same type of anti-CRT legislation passed in dozens of other states would be embraced in Indiana, which considered a ban on “divisive concepts” that could make students feel guilt or discomfort because of their race or ethnic background.

But several gaffes from Republican legislators — Sen. Scott Baldwin said educators should remain impartial in teaching about Marxism, Nazism and fascism, for example — and pressure from advocacy groups ensured its demise.

Those same activists are already pushing for the NAACP’s success.

Brandon Brown, CEO of The Mind Trust, an Indianapolis-based nonprofit that has helped launch dozens of new schools in the city, including many charters, is hopeful about the plan’s prospects. He said there is a growing acknowledgment from critical stakeholders that racial achievement gaps are unacceptable.

“The NAACP has gotten a wide variety of audiences with state-level leadership who have been amenable to the data and strategies they laid out,” he said.

The civil rights group is not yet collaborating with specific legislators to further its agenda. But it does have a list of priorities it hopes to achieve: It seeks full-day kindergarten — right now, children are not required to attend school until age 7 — and quality preschool for all, a revised school funding formula focused on equity, the creation of a legislative Department of Education equity officer and funding for “grow-your-own” school programs designed to recruit and retain Black teachers.

“Each of these legislative items require the advocacy efforts of all of the voting citizens of Indiana and especially those organizations that lobby and have connections with legislators,” Craig said.

Been here before

But some of what the NAACP proposes mirrors what was already agreed to by the state as part of its ESSA plan. Unfortunately, Indiana has struggled with the benchmarks established through the Obama-era directive.

Indiana’s ESSA plan was first implemented in the 2017-18 school year and pledged to “close its student achievement gap in English/language arts and mathematics for all student groups by 50 percent by 2023 for high school and by 2026 for elementary and middle school.” But the state couldn’t meet the commitment — COVID alone marked a major setback — and has since asked for an extension.

“It’s one thing to have it in the law,” said Mark A. Russell, director of education and family services for the Indianapolis Urban League, speaking of ESSA. “It’s another to have it enforced. The patterns that are so prevalent for Black students have continued unabated. In fact, they have worsened since ESSA was first adopted.”

And it’s not the only time the state has failed to live up to a prior pledge. Indiana passed a cultural competency law in 2004 that was supposed to better prepare teachers for the classroom. But, so far, it has not materialized, activists say.

“We are still trying to make sure it was being enacted,” said Gwendolyn J. Kelley, NAACP Education Committee member and the report’s lead editor. “It was as if a law was passed and put on the shelf and no one was monitoring it.”

But even more than monitoring existing laws or adding new ones, Kelley and other NAACP leaders face an even tougher battle: ending the state’s tradition of failing to recognize Black students’ talent.

“The whole idea of high expectations for children is key,” Kelley said. “When people’s mindsets change, they will implement all of the strategies we have in place.”

Disclosure: The Mind Trust provides financial support to The 74.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)