Alliance College-Ready Public Schools: AMPing Up Its Alumni Network to Track & Guide Students Through College

This is one chapter in an ongoing multimedia series by Richard Whitmire called The Alumni, which focuses on the efforts being made by America’s top charter networks in guiding alumni to — and through — college. Read all our school profiles here, and be sure to visit The Alumni microsite to see other essays, videos, graphics, and profiles of the educators and students leading a college success revolution: TheAlumni.The74Million.org.

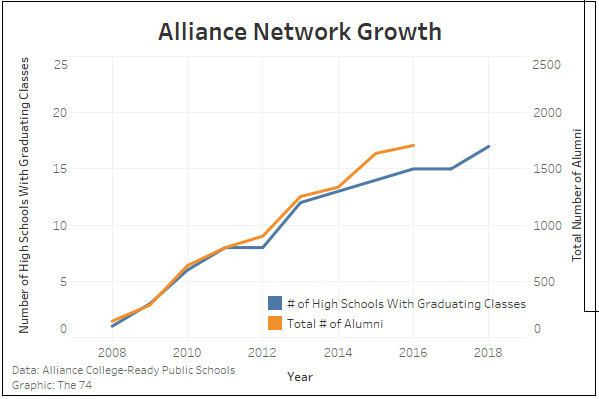

With 15 high schools in its network now, Alliance has grown from just eight schools five years ago. In total so far, there are 8,712 high school graduates of Alliance schools.

That rapid rate was calculated to meet a demand from parents who wanted high schools in which, compared to the traditional L.A. schools, students were far more likely to earn high school diplomas and enter college. When Alliance opened its first high school in 2004, only 49 percent of students in traditional LAUSD schools graduated from high school.

Alliance is posting those gains now, but that comes five years after the charter network realized it had a problem: Far too few of its alumni were actually earning college degrees. At that point, Alliance put together a team to track its students after graduation.

But compared to the charter networks with higher college success rates, Alliance was late to the charter school game. That, plus being challenged by its rapid growth, probably explains why Alliance has a low proportion of alumni who graduate college within six years: 25 percent.

That’s better than the 9 percent of students from low-income families who earn college degrees within six years, but well below other charter networks, where half of their graduates earn college degrees within six years.

All three California charter networks profiled in The Alumni, Alliance, Aspire, and Green Dot, ended up at the bottom of the college success rankings. The reasons for that appear to lie in the state’s erratic funding over the past decade, first slicing per-student K-12 funding to the bone, followed by severe cuts to the state university system.

At a time when charter networks elsewhere in the country were expanding their college success programs, the California charters were struggling just to stay afloat. And when their students entered the beleaguered state university system, they struggled to win seats in classes mandatory to stay on track for graduation. Middle-class students could afford to wait it out; not these students. Many gave up and took jobs.

So the relevant question is how the college success rate at Alliance compares to Los Angeles Unified. Hard to say, since LAUSD, like nearly all traditional districts, doesn’t track its students that far. But we do know how many LAUSD graduates enter four-year colleges: 24 percent, compared to 49 percent of Alliance graduates.

Another factor to consider: LAUSD includes far more upper-income parents coming from schools in neighborhoods like Brentwood. About 78 percent of the district students are considered disadvantaged, compared to 97 percent of Alliance students. And the racial mix is different as well, with far more white and Asian students in district schools. At Alliance, those students make up just 2 percent of the student population.

Alliance may rank near the bottom of the major charter networks in terms of degree-earning rates, but it still significantly outperforms L.A.’s traditional district.

A GreatSchools study published this May identified “spotlight” schools where black and Hispanic students fare far better than the city’s district at large. Several Alliance charters ended up on that list. Alliance estimates that its students score 82 percent higher in math and 48 percent higher in English, compared to students at neighboring traditional public schools.

Until recently, Alliance schools operated like traditional high schools, which measure themselves only by the percent of students winning high school diplomas — perhaps supplemented by the percentage of their graduates committing to enroll in college, which is an unreliable measure. Many students just don’t show up for the first day of classes, or drop out after the freshman year.

The idea that high schools should track their students through college, and then calculate the number of their alumni earning degrees after six years, is both new and radical. The assumption has always been that it was the job of colleges to worry about how many of their students earn degrees.

In researching The Alumni, I came across very few traditional school districts that track their students through college, and those were collaborating with charter schools.

Even today, Alliance’s alumni tracking efforts are modest, at least compared to the extensive programs devised by networks like KIPP, which employs teams with precise student caseloads, tracking them with software from Salesforce — an expensive endeavor.

At Alliance, only three people oversee the effort, and there are no caseloads. Rather, Alliance relies on improving its college selection process using a list of colleges more likely to guarantee success for its unique students, almost all of whom are low-income and minorities and then supporting them in college with a student mentor program known as AMP, Alliance Mentorship Program.

The 135 mentors who take part in AMP — all of whom are Alliance alumni — receive modest stipends and keep track of five to eight recent Alliance graduates. That approach keeps costs down for Alliance, which sets a goal to prove it can do a better job educating low-income students without spending any more money than what traditional L.A. high schools receive.

The Alliance Marc and Eva Stern Math and Science School is an Alliance school located on the campus of California State University, Los Angeles. Both college counseling at the high school and the AMP program at the university were taking place in late April.

Seniors were scheduled for exit interviews, during which a high school counselor or “college success” team member sits down with a high school senior and reviews his or her college plans. This particular day also happened to be one week before seniors had to commit to college.

In each case, Linsley updated student files, reviewed where they had applied and where they had been accepted and rejected. He then analyzed the details of their commitments. Almost all the planning revolved around financials.

The first student to meet with Linsley that day was Karina Rodriguez. The shy 17-year-old’s mom stays at home while her dad sells fruit from a truck. On weekends, she helps sell fruit as well.

Rodriguez had been accepted at the University of California, Los Angeles, a highly prestigious and selective public university — an accomplishment that history and data would defy for a student of her background.

Rodriguez, who wanted to study environmental engineering, was also accepted to New York University, but she never considered moving to New York — the Big Apple is simply too far from family.

Alliance senior Karina Rodriguez.

At UCLA, grants and scholarships were expected to cover all but $24,000 over four years, but that was still a scary figure for Rodriguez, who had no money saved for college.

Rodriguez appeared to prefer living at home and commuting to UCLA, which concerned Linsley, who was busy scanning the student’s online financial aid package from UCLA. The aid package, he concluded, would cover room and board. To top that, the commute could take up to two hours one-way.

“In the long run it’s going to be better for you to live in [university] housing, especially the first year, when you’re acclimating to academics,” Linsley told Rodriguez. “Plus, you would have no social life.”

Rodriguez looked worried, and while her heart appeared to be more comfortable living at home, she promised to change her application to apply for student housing.

On the same day, Kiara Ramirez was confidently wearing a Smith College sweatshirt and a big smile, and feeling good about her decision. The estimated cost of a Smith education is $72,000 and the financial offer covers $70,000 of that, she said. Her study interest: chemistry.

Simon Linsley, director of college success at Alliance, with senior Kiara Ramirez.

As Linsley examined the aid package, he noticed there were no transportation allowances. His estimate: Going to Smith would cost Ramirez $20,000 over four years. For an Alliance student, that’s a lot.

He then pointed out that Ramirez hadn’t actually accepted Smith’s offer — and had only a week to do so, and he told her as much. Suddenly, her cheerful demeanor disappeared. She looked worried, which Linsley quickly sought to absolve.

To help Ramirez manage all her needed actions over the next week, Linsley built a to-do list in an email, which he sent to both Ramirez and her counselor.

The AMP mentee on the adjacent college campus, Cal State L.A., was sophomore Vanessa Najarro, a criminal justice major who one day would like to join the FBI. Adjusting to college life meant learning how to be more organized and how to seek out professors for help. When she was an Alliance high school student, the teachers were always available. The college social life was also an awkward adjustment.

“It can be nerve-racking to get out there and actually talk to strangers,” Najarro said. “In high school you see your friends every day.”

On one day, she was being mentored by Alliance alum By’Ron Williams, who walked her through a checklist of questions supplied by Linsley’s program. Next year, Najarro wants to become a mentor.

Cal State L.A. freshman Vanessa Najarro, a graduate of Alliance College-Ready Public Schools, gets counseled by an upperclassman there, also an Alliance alumnus.

“It’s really helpful. They teach you how to build résumés, how to network. These are life skills that you don’t get in high school,” Najarro said. “AMP mentors have also helped with financial aid questions. But it’s also about becoming a better person, building yourself up.”

Najarro was accepted to the University of California, Merced, which is both a more prestigious university and a place from which she is more likely to earn a degree. But that seemed too far away.

“I really like L.A., and I felt like I would get homesick,” she said.

Being at Cal State L.A. allows her to live at home and work 20 hours a week as a cashier, which is necessary to pay off college debts. But those same distractions explain why the Cal State L.A. graduation rates are so low: Only 19 percent of the students earn degrees within six years, in part because of the many work and family obligations and distractions.

Najarro agreed that there are more challenges, especially time management issues arising from being a full-time student and working 20 hours a week.

Part of her motivation came from being the first in her family to go to college. “I have a good GPA,” she said. “I feel like I have to be a good role model for my brothers.”

One AMP mentor, David Vaca, described the many pressures he hears from his mentees — pressures familiar to him, because he experienced the same, only without benefit of a student counselor. Feeling overwhelmed with classwork and worrying about failing are only two of the pressures. “It’s also work. They feel pressured by their parents. I can speak for myself. I felt pressure to get a job because I was in college, everything was getting more expensive — food, books,” Vaca said. “So they have to take on that extra job, plus the four classes already and also the pressure to also get involved into some campus activities. They could probably lose track of one of those things, like their education.”

Vaca knows he can’t solve all their problems, but just having someone to talk to makes a difference.

“I can hope that they won’t ever feel alone, because it definitely is a scary place out here,” he said. “You definitely feel alone a lot. Overwhelmed.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)