All States Now Required to Track Students’ College and Career Readiness, but Few Do It Well and Some Not at All

Here’s a one-word summary of how the nation’s high schools are doing with the college and career readiness indicators now required by federal law: Spotty.

Four states — Alaska, Maine, Nebraska and Oregon — aren’t reporting any college and career readiness indicators, such as advanced courses taken or college enrollment, according to Bellwether Education Partners in its newly released “College and Career Readiness, or a New Form of Tracking?”

Most of the rest of the states are mostly going through the reporting motions without posting much that’s useful for parents, who are worried about how their sons and daughters will fare in the future, whether it be college or a career. In many states, such as Delaware and Louisiana, credentials such as cosmetology can count the same as an Advanced Placement class toward meeting college and career goals. But should parents believe those are equivalent? Do they carry the same value?

Too few states (16, to be exact) break down their readiness data by race and poverty, which is absolutely crucial and which federal law mandates. But even in those states, parents have to act as online data sleuths to find the information.

True, there are some standout states, such as Illinois, where parents can easily find their own schools online and click on a drop-down menu that tells them how many ninth-graders are on track academically, along with how many students are taking early college courses and AP courses. They can also see the number of students enrolling in two-year colleges versus four-year colleges.

“That’s useful,” said Bellwether’s Lynne Graziano, who co-authored the report. “Parents will know how likely their children are to go to postsecondary education.”

But most states are uneven, at best.

“We see states giving college and career readiness a lot of attention,” said Graziano. “But I’m not sure we have the right pieces in place to make it as meaningful as it could be.”

Most damning: While some states include college enrollment as one of their indicators, there’s no effort to follow that up beyond enrollment.

Here’s what high schools miss out on by not following through: Are our alumni actually earning degrees? Among those who are earning degrees, are there wide gaps based on race and income? Most importantly, what are we doing right or wrong during the high school years to prepare students for college, a career or the military?

What Bellwether ran up against in its research is what I found in researching The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. With few exceptions, high schools stick to their traditional mission: ensuring that as many of their students as possible walk away with high school degrees.

Attempts to refocus superintendents and principals to the broader mission of tracking their students through college, for example, quickly run aground. Their answer: How can you hold us accountable for factors over which we have no control? College success, or failure, is up to the students, their parents, and the colleges, they argue, mostly in private.

Perhaps, but over the past decade some top charter school groups pioneered college tracking strategies that, in a few cases, have pushed the college success rates for their low-income minority students, as measured by who actually earns degrees, to levels that match the rates for white students from well-off families.

The twin strategies behind boosting college graduation rates for first-generation students are providing data-driven college advising (where are our alumni most likely to earn degrees?) and then tracking their progress through college, stepping in to assist when students go off track.

The most important data are available through the National Student Clearinghouse, a nonprofit located in Herndon, Virginia, that was originally launched to keep track of student loans. In recent years, however, its StudentTracker data have been put to use to boost college graduation rates. For a rate of only $425 per school, high school leaders can get eight years of data on how their students fared after graduating.

Few high schools, however, make full use of the data.

The students who are hurt most when high schools neglect college and career readiness are low-income, minority students, the same students feeling the most pain from the college turmoil caused by the pandemic.

If states don’t disaggregate their readiness data, there’s no way to know whether Black and Latino students are getting into higher-level courses such as Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate, the courses most likely to prepare them for college or career training.

And that neglect is exactly what happens, concludes The Education Trust in its “Inequities in Advanced Coursework” report.

“No student should forfeit future success because there were not enough seats in the class or because the seats were not available,” wrote report author Kayla Patrick.

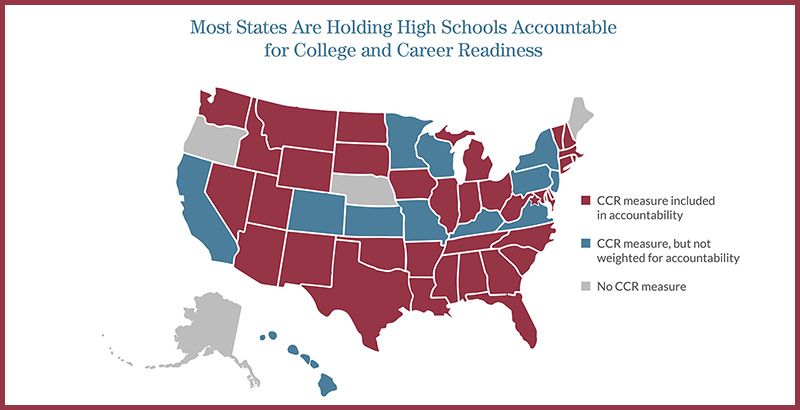

The solution, according to the Bellwether report, is for every state to develop college and career accountability systems and then fold them into high school rating systems. From the report: “Accountability systems encourage all schools in a state to get more students enrolled in and completing college and career pathways.”

Disclosure: Andy Rotherham co-founded Bellwether Education Partners. He sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)