ALICE, America’s Most Controversial Active-Shooter Training that Teaches Kids to Fight Back, Saved Dozens of Lives in Oxford HS Attack, CEO Claims

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As gunshots rang out inside Michigan’s Oxford High School last week, terrified students scrambled for shelter, barricading classroom doors with desks and chairs should the gunman try to burst inside. Some wielded scissors and calculators as makeshift weapons in case they had to fight back.

One student, 16-year-old star running back Tate Myre, was reportedly shot as he charged toward the gunman in an attempt to stop the mayhem. He died while being rushed to the hospital in the back of a deputy’s squad car.

For many, the scene symbolized a harrowing reality: After years of routine drills, the school’s students — members of the “lockdown generation” — seemed to know how they should act under fire. For the ALICE Training Institute, among the country’s most controversial school security groups, scenes from inside the school were validating. Oxford students underwent ALICE’s active-shooter training in October, a fact that Oakland County Sheriff Mike Bouchard said likely saved lives.

The Oxford community “would have seen three to 10 X the number of deaths” without the company’s guidance, JP Guilbault, CEO of Navigate360, which owns ALICE, told The 74. Such casualty claims would have made the Oxford shooting — where four students were killed and six students and one teacher injured — the worst mass school shooting in U.S. history.

“Based on student accounts, it was clear to me the school went well into preparing their kids for something they hoped they would never see,” said Guilbault, who leads the country’s largest for-profit provider of active-shooter drills. “But those kids were prepared.”

Almost all schools in America conduct active shooter drills despite a growing concern in recent years that they’re ineffective and traumatize students who are forced to grapple with their mortality on a regular basis. Dubbed “America’s scariest school shooter drills” by one news outlet, ALICE has repeatedly found itself at the forefront of controversy. In a 2019 ALICE training incident, for example, law enforcement officers who led a mock school shooting shot Indiana teachers with plastic airsoft pellets, leaving welts and bruises on the unsuspecting educators. The episode led school safety experts to denounce the drills.

Now, the high-profile Nov. 30 shooting in Oxford, which resulted in the very rare circumstance of both the 15-year-old suspected gunman and his parents being charged, has reignited a tense debate about how to prepare students for the possibility that they could find themselves under attack. In a letter, Oxford Community Schools Superintendent Tim Throne said the district plans to hire an outside security consultant to review its safety practices.

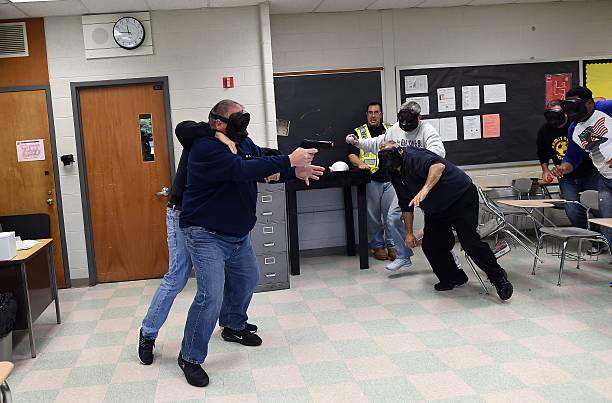

ALICE — an acronym for Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter and Evacuate — employs a model that goes far beyond traditional lockdown drills that the company and its proponents say offers a toolbox of options as an attack unfolds and increases students’ odds of survival. Yet critics argue the institute’s training doesn’t just traumatize children, but could put them at greater risk of getting killed.

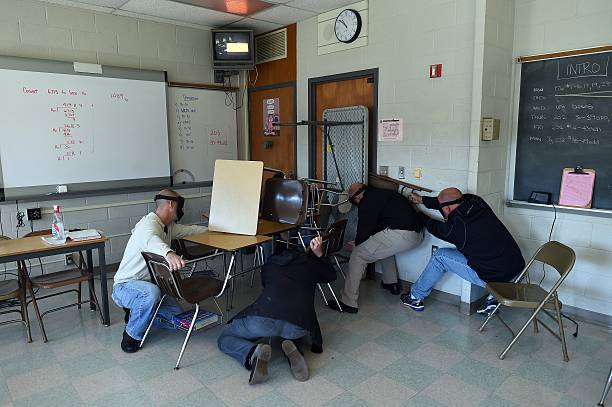

Traditional lockdowns teach children to bolt classroom doors, turn off the lights, move as far away from windows and doors as possible, stay completely silent and wait for emergency responders to arrive with help. Along with locking doors, “multi-options” approaches like ALICE teach students to barricade the doors with desks, chairs and other environmental objects and to self-evacuate if they feel it’s safe. As a last resort, ALICE teaches students to “counter” — or fight — the gunman.

Teaching kids to fight off a gunman is by far ALICE’s most contentious lesson. But Guilbault, the CEO, said that traditional lockdowns teach students “to just sit in place” and conditions “the natural freeze process” when confronted with a deadly threat. By presenting multiple avenues of response, Guilbault said, ALICE strengthens students’ chances of coming out of such lethal encounters alive. The factors most critical to survival, he said, are “time and distance.”

“Should a door get breached, your job is to figure out how to give yourself time and distance,” including through distraction techniques like throwing books and other classroom supplies, he said. “It’s clear the kids were getting ready, if that door was breached, to throw objects and to give themselves the best chance of surviving.”

In one viral video, a classroom of students were shown engaging with someone through a barricaded door who identifies himself as a member of the sheriff’s office. Skeptical of the man who tells them “it’s safe to come out,” students flee the room through a window. Guilbault said the students made the right decision when they refused to open the door because they were unsure who stood on the other side. Yet he said he would have instructed them to remain silent rather than engage in a conversation with the man. The sheriff later said the man was not the gunman, but was most likely a plainclothes police officer.

Though Guilbault declined to comment on reports that Myre, one of the shooting victims, had charged toward the gunman, he advised against the strategy.

“Fighting is a last resort,” he said. “We teach individuals that are not first responders to move away from danger, not towards it.

Drills raise competing philosophies

School safety consultant Kenneth Trump, the president of Cleveland-Based National School Safety and Security Services, is among the institute’s most outspoken critics. K-12 students’ brains haven’t fully developed and many lack the capacity to fight off a gunman, Trump said. Meanwhile, students self-evacuating from the school could increase their odds of getting shot, he said, while inhibiting police officers’ ability to pursue the shooter.

Students are being asked “to make split-second decisions that trained law enforcement and military professionals still struggle with” when confronting an armed gunman, said Trump, who endorses traditional lockdowns during active shootings.

Research on the efficacy of active-shooter drills is limited, but one 2018 report in the peer-reviewed Journal of School Violence used simulations to test ALICE against traditional lockdown drills. Traditional lockdown drills ended when the shooter ran out of ammunition, researchers found, while participants using ALICE techniques were able to thwart the attacker. The study’s results, the authors wrote in an op-ed, “brings into serious question if traditional lockdown should still be considered as the sole response to these types of events.” The sophomore charged in the Oxford shooting had 18 rounds of ammunition still on him when he quickly surrendered to police.

Trump challenged the study’s independence and rigor. One author works for ALICE and the others are certified ALICE instructors. Police officers made up a large share of simulation participants and children weren’t included.

Study co-author Cheryl Lero Jonson, an associate criminal justice professor at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, denied that any conflicts of interest exist between her being a certified ALICE instructor and her research.

ALICE relies on a train-the-trainer model to put its method in front of millions of kids across the country each year. Through a two-day course, educators and police learn the ins and outs of the approach before passing its lessons on to youth. Guilbault said that multiple Oxford officials are ALICE instructors and the district has been a customer for several years, but declined to comment on who went through the company’s certification process.

“We don’t put smoke in a school to practice for fire or big fans in the school to practice for a tornado. Personally, what I think is happening, it’s rogue instructors.”

—Cheryl Lero Jonson, associate criminal justice professor and certified ALICE instructor

ALICE’s train-the-trainer model allows for a wide degree of variability, Guilbault said. Oftentimes, the drills are conducted by local police, who are accustomed to tactical training, and are conducted to mimic real-world shooting simulations — a tactic Guilbault said “is common in law enforcement, but it’s not applicable for kids or teachers.” Numerous examples suggest such simulations have long been used by ALICE trainers. Guilbault said that ALICE instructors must take students’ age into consideration.

The result, Trump argued, is a training model that resembles the “telephone game” that’s left some districts undergoing full-scale simulations that resemble real-world mass shootings.

“It leaves a lot of room for interpretation to the point where we’ve seen some very extreme cases” including incidents where administrators told kids to keep cans of soup under their desk to throw at any potential gunmen. “Those variations have left people scratching their heads going, ‘What are you thinking?’”

Johnson said that ALICE “adamantly opposes’ full-scale active shooter simulations with weapons and fake blood because it “causes undue trauma” in children.

“We don’t put smoke in a school to practice for fire or big fans in the school to practice for a tornado,” she said while acknowledging that simulations have been central to multiple ALICE-related controversies. “Personally, what I think is happening, it’s rogue instructors.”

Drills prompt psychological concerns

Some education leaders and school safety experts have challenged the premise of active shooter drills altogether, pointing to a growing concern that active-shooter drills traumatize the kids who are forced to endure them.

Last year, the American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association and the Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund called for an end to unannounced active-shooter drills that simulate gun violence. Also in 2020, Everytown researchers analyzed about 28 million social media posts and found the timing of active shooter drills were correlated with an uptick in posts that signaled stress, anxiety and depression among students, parents and teachers.

Jonson, the Xavier University researcher, has pushed back. In a report last year, she found that students are no more fearful of ALICE training than tornado drills. Just 1 in 10 surveyed students reported feeling a negative psychological outcome from ALICE. The 2019 survey was conducted in a single unidentified school district in the Midwest, which used discussion-based instruction rather than simulations.

Forensic psychologist Jillian Peterson, an associate criminal justice professor at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota and co-founder of The Violence Project, said the national conversation about school shootings has focused too much attention on “target hardening” and responding to shootings rather than heading off the tragedies from unfolding in the first place. Peterson promotes a greater emphasis on preventative strategies like improving mental health supports in schools, creating welcoming campus environments and establishing anonymous reporting tools where students can alert the authorities to their peers’ troubling behaviors.

On two occasions just before the Oxford shooting, teachers sounded the alarm about the suspected gunman’s concerning behavior. On the morning of the shooting, the student and his parents met with guidance counselors to discuss his behaviors but he was ultimately allowed to return to class. Several hours later, police say, he walked out of a school bathroom and opened fire. The factors leading up to the shooting will likely be explored in the independent review of the school’s actions

“What was that experience for this perpetrator when he went through this ALICE training a month ago?”

—Jillian Peterson, associate criminal justice professor and co-founder, The Violence Project

Active shooter drills in particular, Peterson said, fail to account for a reality that most school shooters are insiders. Her research has found that 91 percent of school shootings are carried out by current or former students. Along with concerns the drills could lead to heightened anxiety and increase the perception that statistically rare school shootings are commonplace, Peterson said that active shooter drills — including the one recently carried out in Oxford — could teach gunmen how officials will react under siege.

“If it’s an insider going through all of that with everybody else, with all of that information, then that approach just stops making a lot of sense,” Peterson said. “But that also opens up all of these new avenues where you can say, ‘Hey, it’s a kid in this school who is going to do this. How do we make sure, as a school, that none of these kids are going to want to do this?’”

Meanwhile, there’s a growing concern that school shootings are “socially contagious,” in which one mass shooting has a tendency to spark additional violence in the immediate aftermath as vulnerable people considering violence seek fame after reading about shootings and identifying with the gunman. Following the Oxford shooting, schools nationwide were confronted with a wave of “copycat” threats.

Frequent active shooter drills, Peterson worries, could plant a seed by placing so much attention on school shooting preparedness.

“When we’re running students through this over and over and over again, what is that doing in terms of increasing fascination, in terms of having students think through this again and again?” she asked. “What was that experience for this perpetrator when he went through this ALICE training a month ago?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)