After Contentious Vote, Hebrew Charter Founder Eyes Jewish School in Oklahoma

Last week’s decision approving a Catholic charter puts the state in middle of an uncomfortable intersection of church, state and market forces.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A former Democratic congressman who founded a network of Hebrew-language charter schools in Florida hopes to launch the second explicitly religious charter in the nation.

The idea for a Jewish charter school in Oklahoma could gather steam following last week’s hotly contested vote to approve a virtual Catholic charter school in the state.

“This is the logical progression in terms of what the Constitution says,” said Peter Deutsch, who veers sharply from his party on the issue. “I still believe in a lot of things the Democrats believe in, but school choice is a civil rights issue in this generation.”

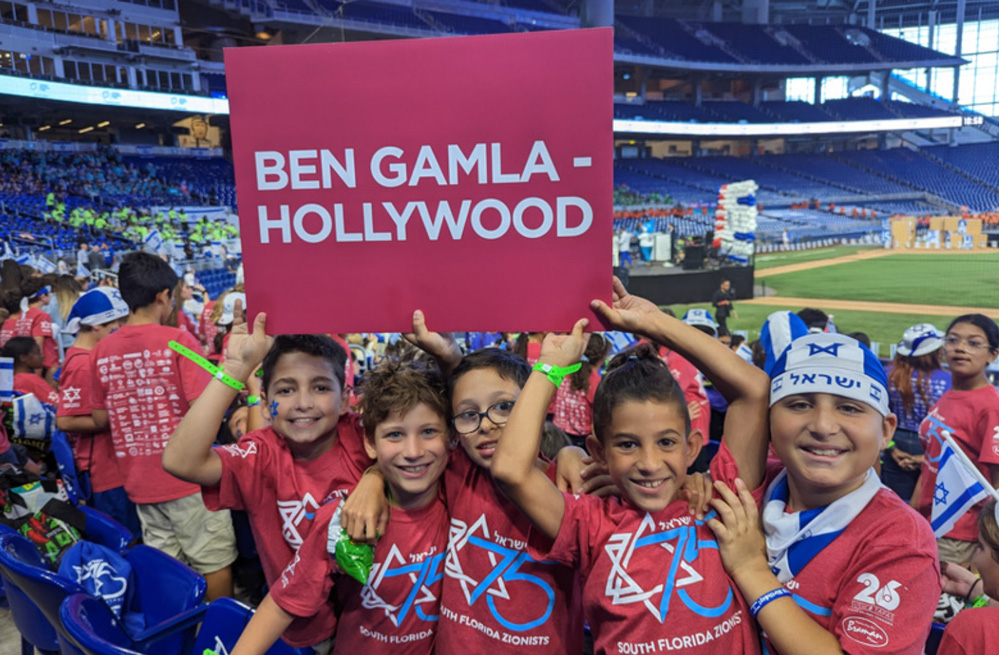

A Jewish charter would allow Deutsch to offer families something he couldn’t when he founded Ben Gamla Charter School in Hollywood, Florida, in 2007 — an education not only focused on Hebrew language, culture and history, but the tenets of Judaism.

It also opens a window into a sometimes uncomfortable intersection of church, state and market forces as Oklahoma pushes the nation into uncharted legal territory.

“I always know it’s a hot topic when my phone blows up before it’s on the cover of the Wall Street Journal or CNN,” Maury Litwack, founder of Teach Coalition, said Friday during a webinar about the Catholic charter. With groups in Florida, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania, the coalition is affiliated with the Orthodox Union, which supports synagogues and youth programs.

Deutsch visited Oklahoma in January to meet with Jewish leaders. But not all groups share his interest. After last week’s vote, the Jewish Federation of Greater Oklahoma City, a nonreligious group, called the charter board’s decision unconstitutional.

The Statewide Virtual Charter Board voted 3-2 to approve the St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School despite warnings from Attorney General Gentner Drummond that it violates state law.

Drummond is currently reviewing that vote. In his opinion, a board member added just three days before the decision technically shouldn’t have voted because state law says new appointments don’t take effect until Nov. 1. Bob Bobek, a former state board of education member, replaced Barry Beauchamp, a retired superintendent. Before the vote, Robert Franklin, the board’s chair, asked Bobek to recuse himself, but he refused.

The possible invalidation of the vote would likely be only a temporary setback because the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa can appeal to the state board. Brett Farley, executive director of the Catholic Conference of Oklahoma, a policy organization, said he has even “more confidence in that scenario” because Gov. Kevin Stitt, who strongly supports the application, appointed the board members.

The case for religious charters could also get considerable ballast if the U.S. Supreme Court agrees to hear a federal case from North Carolina that asks whether charter schools are public or private. On June 22, the U.S. Supreme Court will discuss whether to hear Charter Day School Inc. v. Peltier, in which a charter school argues that because it’s a nonprofit, it should be free to enforce a dress code requiring girls to wear skirts.

Both charter leaders and advocates for religious freedom say the court could help settle the debate over whether charters can explicitly teach religion. If the court declines to hear it, a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit that charters are public schools acting on behalf of the state would stand.

“The 4th Circuit is a major loss” for those pushing for religious charters, said Derek Black, a University of South Carolina law professor. “And if the Supreme Court declines to hear it, that is a major affirmation of that loss.”

But others agree with Deutsch that some parents want publicly funded educational options that include faith-based schools.

“Yes, we have to follow the law,” Lynn Norman-Teck, executive director of the Florida Charter School Alliance, said about the state’s requirement that charters be nonsectarian. But she added that charter schools “absolutely” have to understand parent demand “and the evolution of education.”

She remembers when Deutsch was trying to convince the Broward County Board of Education to approve the first Ben Gamla school, two years after he left Congress following a failed Senate run.

Some worried it would be hard to divorce the instruction of Hebrew, the language of Judaism, from teaching the faith itself.

Eleanor Sobel, then a school board member and later a state senator, was among the most outspoken opponents, telling reporters that it would be nearly impossible to monitor whether Judaism was actually part of the curriculum. Even after it opened, the board told the school to stop teaching Hebrew until officials were satisfied that teachers weren’t advocating religion. The restriction was lifted a few weeks later.

Norman-Teck said she doesn’t hear those concerns anymore and that Ben Gamla, now a network of six schools, serves a diverse population including Black and Caribbean students.

“They proved the board wrong,” she said. “They were very careful that that line wasn’t crossed.”

But a lot has changed in Florida in 16 years. If he was developing the school today, Deutsch said he would establish “a Jewish voucher school” because of the explosion of private school choice in Florida. In fact, 40% of students in Florida’s Jewish day schools were receiving a state scholarship even before Gov. Ron DeSantis signed legislation in March that made all students eligible for a voucher or education savings account worth about $8,500.

Ironically, an Oklahoma charter would allow Deutsch to accomplish something his critics in Florida feared he would do there: create a public school with an explicitly Jewish curriculum.

With the political hurdle in Oklahoma largely eliminated, Deutsch said his biggest problem might be practical: finding enough interested Jews to fill a school.

“I spoke with every Jew I could find near Oklahoma City,” Deutsch said. Currently, that’s a small number; only about 4,400 of Oklahoma’s nearly 4 million residents are Jewish. But he added, “There are families that I believe would move to Oklahoma if there was a Jewish religious charter school.”

Friday’s virtual webinar featured Michael Helfand of Pepperdine University and Notre Dame University’s Nicole Garnett — both law professors who focus on religious liberty. Garnett argues religious organizations that want to open charters should be able to receive public funds, much like faith-based adoption agencies and soup kitchens.

But Helfand is less convinced that if the Supreme Court takes up the North Carolina case, justices will rule that charters are private. Despite recent decisions favoring public funds for religious schools, he expects the court will decide it’s time for some “boundaries on this kind of general momentum.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)