A Student’s View: Thinking Outside the Device — With a Little Ingenuity, Libraries Could Keep Kids Loving Reading While Schools Are Closed

The transition to distance learning has caused unprecedented disruption to our education system. Many low-income students do not have internet access necessary for taking classes online. While some districts and charter schools are distributing devices and hotspots, in others, students are making do with paper packets.

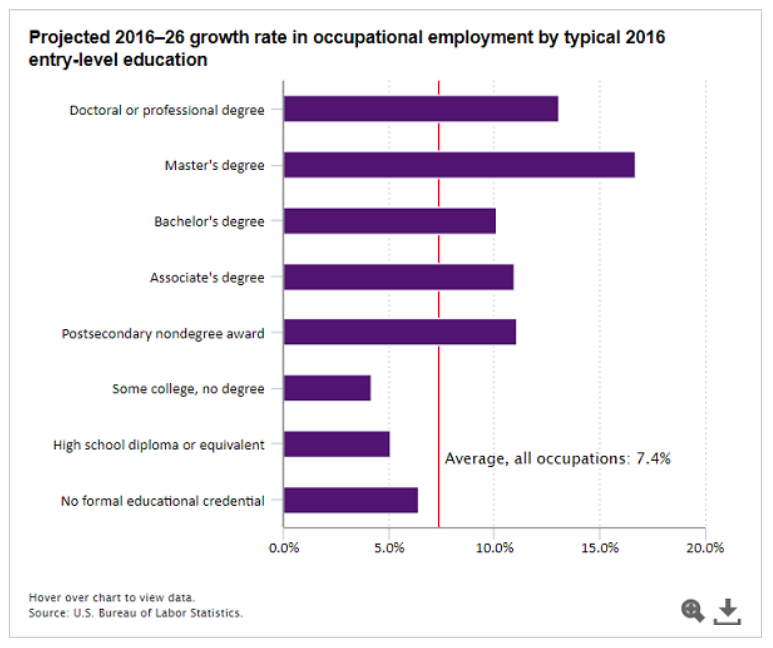

With all this chaos, though, we still live in an economy in which most occupations will require more than a high school diploma in the near future. Students must be prepared with an adequate education.

So let’s think creatively about what we can do to help. One constant resource for kids of all ages is the local library. Why not begin by opening libraries and using them as one way to bridge the gap? Reading is the gateway to learning, and nothing is more valuable to children than developing a love of reading. Yet according to a recent survey, only 56 percent of American students read for enjoyment.

Could we use this moment to help cultivate that love?

Widely available antibody testing is inching closer to reality. It could soon be possible to partially staff libraries with employees who have recovered from the coronavirus, who are therefore more likely to be immune, and who volunteer to return to work.

After libraries are deep cleaned, librarians could curate recommended reading lists and encourage children to check out books from them. Teachers could also develop reading lists and periodically ask their students for book reports, to demonstrate that they’re participating.

This would not be a replacement for online learning; rather, it would be a supplemental solution that could reach all students equitably and without requiring too much parental assistance. For some families, it would provide a welcome break from their new teaching duties.

With at least 20 states already closing schools for the rest of this academic year, summer is starting early for many students. Even during a normal summer, many students, especially lower-income children, lose up to 30 percent of what they learned the prior year; an anticipated “COVID slide” is likely to make things even worse.

To combat summer slide, schools have long promoted summer reading programs, which have been shown to improve literacy for low-income students. Accessing good books could provide an escape during the long months between now and the fall. And perhaps students who never read for pleasure before could get hooked on books.

To communicate about the program, schools and districts could send out emails and put flyers in the free meals distributed to students at grab-and-go meal sites and bus stop deliveries.

To maintain social distancing, libraries could designate specific days of the week for different grades. Students would line up outside their library on their designated day, six feet apart, wearing masks and gloves. The libraries could make books from their reading lists available on tables just outside or inside the door. Children could then take turns choosing their next books.

A week later, they would return what they took in a paper bag and check out new books. Librarians would allow bags of returned books to sit for 72 hours — the virus’s lifespan on plastic — before handling. For an extra precaution, libraries could even remove the plastic covers typical of most library books.

Districts and charter schools that are distributing hotspots and devices to families with no internet connection could give them out at libraries as well, to reach any families who have not yet received them. Some libraries offered mobile hotspots to residents before COVID-19; there is even more reason to do so today.

As the program would gain in popularity, students would tell their classmates and friends about it. Teachers could even offer rewards for the number of books read and the number of other students recruited to read.

I expect many teachers would be excited to participate, on a voluntary basis, and have the opportunity to see their students again. Communities could organize book drives and create boxes outside libraries to be filled with donated books. The libraries could let the donation bin sit for at least three days, then allow students to take a few books to keep.

This initiative could help meaningful learning continue for all students, regardless of circumstance. And it could fuel a love of reading in a new wave of students, of all income levels.

As Dr. Seuss said, “The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.”

Bruce Arao, a spring 2020 intern at the Progressive Policy Institute, is a student at the University of California, Santa Barbara, double-majoring in economics and sociology.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)