A Program That Successfully Propels Low-Income Students to (and Through) College Starts Its Work Years Before High School

Updated, Nov. 6

Alexandria, Virginia

There’s so much bad news surrounding the failure to boost college graduation rates for low-income, minority students that it’s easy to overlook the good news. Stuff proven to work, such as AVID.

AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination), a national college readiness nonprofit found in many high-poverty schools, now serves 2 million students in 7,000 schools. Until recently, AVID seemed effective mostly because it appeared to be doing all the right things and its research tracking students into the first years of college looked promising. But because college success rates are only calculated six years after a student leaves high school, AVID lacked definitive proof of its effectiveness.

No longer.

AVID now has three graduating classes who’ve reached that six-year point, making a healthy sample size of 82,807 alumni. Among those, 42 percent who are either low-income or first-generation college-goers earned bachelor’s degrees within six years of leaving high school, compared with 11 percent of students from similar backgrounds.

Taking into account all the programs that have failed to improve the odds for first-generation college students, that’s big.

Based on my research done for The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America (published by The 74), programs such as AVID are one of several reasons to be hopeful about turning around the college graduation problems.

The boost to college graduation rates achieved by AVID is strikingly similar to those produced by the big charter school networks that serve the same type of students. That’s not surprising; it’s what happens when students get the right preparation and the right college guidance.

Also optimistic: Many universities, acknowledging their past failures in letting so many fragile students drift away, are doubling down on their efforts to turn that around, both admitting more low-income students and tracking them through college to ensure they don’t drop out.

Even more encouraging: More universities have agreed to ramp up their acceptances of community college graduates, perhaps the nation’s biggest reservoir of low-income students. For years, those students enrolled in community colleges aspiring to win four-year degrees, but few ever made it.

Put it all together and you have the signs of a breakthrough, although a fledgling breakthrough that needs more support to persist.

Having that college mindset

That’s the big picture of what’s playing out nationally around improving college success for low-income students. Now for the little picture.

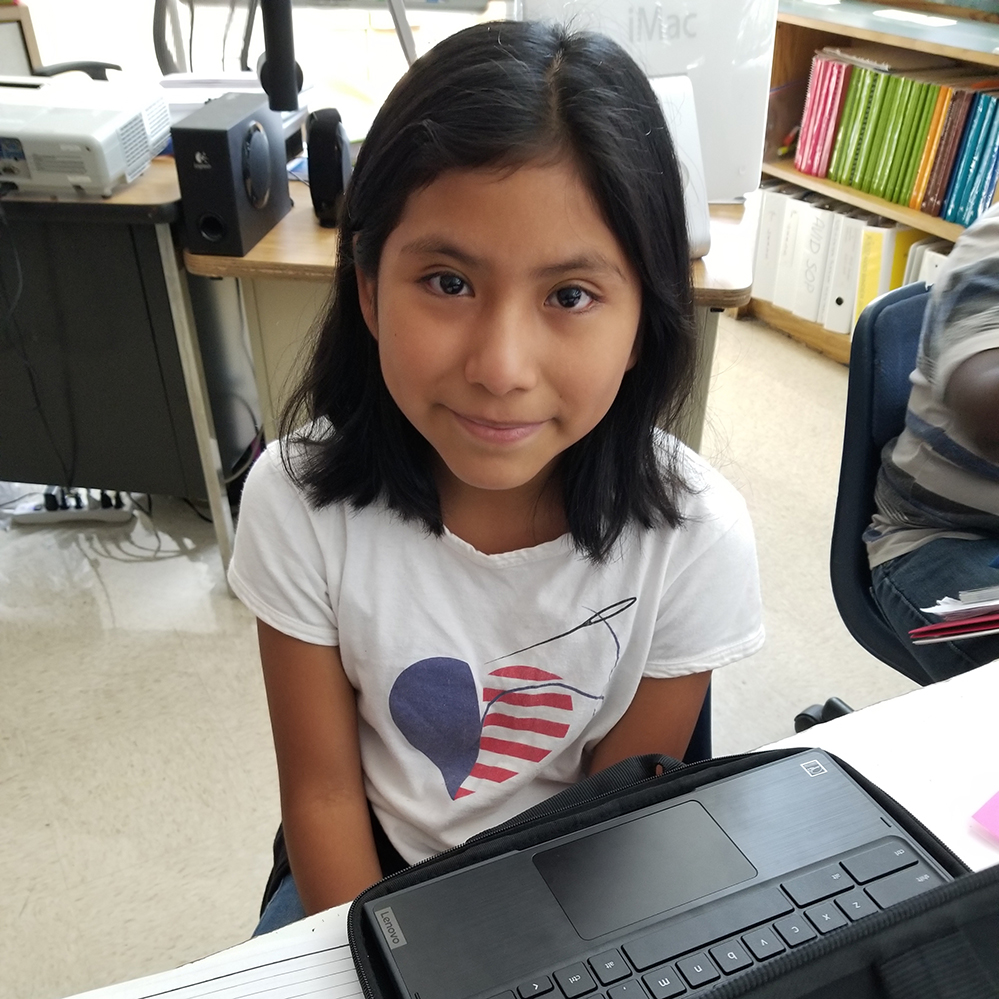

Here at Francis C. Hammond Middle School, part of Alexandria City Public Schools, just a few miles from the U.S. Capitol, the little picture is 11-year-old Berlinda Sabines, born in the U.S. to parents who emigrated from Mexico. She is one of five children in the family, supported by a father working construction jobs and a mother cleaning houses.

Berlinda, a sixth-grader, is clear about why she signed up for Hammond’s AVID classes. Making it through college would send a signal that “anyone can make it,” she tells me. Then she quietly acknowledges another reason to pursue college. The family, she says, struggles at times with finances. “I’m not the richest person.” A college degree would help, she says, tearing up a bit.

Most people think of AVID as a high school program, making sure older students get prepared for entering college, and not just any college — the one where they are most likely to earn a degree. But here at Hammond, and in many school districts, the program launches in earnest in middle school, with fifth-graders applying to sign up for a program that starts the following school year.

Students such as Berlinda enter via teacher recommendation, by a student’s own request or from the school scrubbing test scores to search for unrecognized talent. Many students coming from low-income families may have college potential but don’t think of themselves that way, in many cases because they are English learners.

These are students who “struggle with risk-taking,” such as signing up for honors classes, said Jodie Peters, who oversees all AVID programs for Alexandria schools.

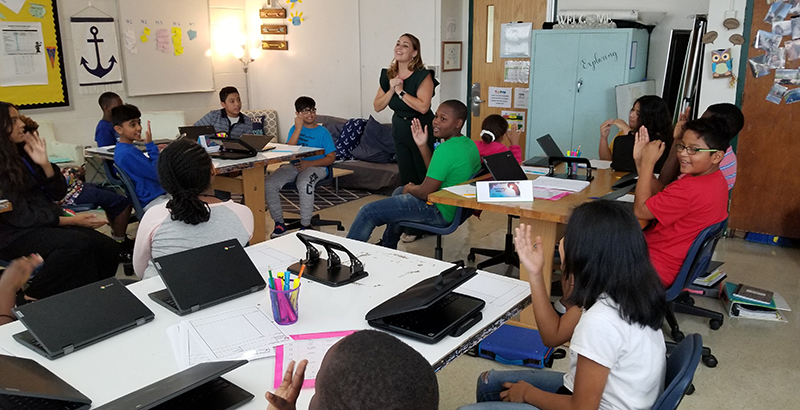

Those who get selected for AVID attend one AVID class a day, where activities range from meeting with tutors to learning skills that will help them succeed in regular academic classes. On the day of my visit, teacher Lauren Vitello focused on note-taking skills. The class of 20 was divided into four groups, with each group practicing different note-taking methods.

One worked on a web, which on paper looks like a spider, with the central idea in the middle and details entered along the spider’s legs. Another group worked on the more traditional Cornell Notes method, where students take notes on the right side of the paper, write thoughts about the notes on the left and then summaries on the bottom. Students at the other two tables worked on two other ways to record notes graphically.

Why learn different methods? Because different teachers have different ways they want students to work, and this allows for flexibility. “It doesn’t matter how you take the notes,” said Fatima Parker from the AVID national staff. “What matters is how you process the notes. This gives them tools for their toolbox — different formats for taking notes and how to process them.”

When I asked Vitello if any of the parents of her 20 students had college degrees, she puzzled over the question and couldn’t think of any. “What all these students have in common is a drive to learn. They all want to do better in classes and go to college. On the first day of class I asked them, if they had to pick a college where they wanted to go, what college would that be? They all knew a college they wanted to go. Some were local colleges; others were colleges where their teachers had gone. But they have that mindset: I want to go to college.”

Hammond, with a high poverty rate among its families, is not what many would see as a school full of students destined to succeed in college. Racial breakdown: 35 percent Hispanic, 15 percent from African countries, 30 percent African American, with the balance a mix. Typical jobs for parents here: blue-collar construction for the dads; retail, fast food or housecleaning for the moms.

There’s only one full-time AVID teacher here, which creates a waiting list to enter the program in sixth grade. In total, the district spends about $140,000 a year on the program at Hammond, a cost that includes the teacher, tutors and materials. Although only 116 students are in the AVID program (that figure includes students in an AVID Excel program that focuses on English language learners), the AVID instructional methods get taught to all the teachers, with about six a year get AVID training, meaning all the middle school students benefit.

Across the 15,737-student district, there are 555 AVID students in all the schools, supported by an $859,000 budget that includes teacher salaries, training for all teachers, student materials, college trips, PSAT testing, tutor support and more.

A vision of a better life

At most schools, AVID funding is a mix of federal, state and local money, combined with corporate and philanthropic dollars. AVID is stronger in some schools than others. One of the most vigorous programs is found in California’s Riverside Unified district, where Scott Lockman oversees a program that includes 640 of the 2,100 high school students there. Of those, 85 percent are Hispanic and nearly 90 percent qualify for subsidized lunches.

Here’s what AVID looks like during the daily elective courses for seniors there:

Monday: AVID tutors scrub student binders to check on the quality of their note-taking. Also, guest speakers, including AVID alumni in college or in the workplace, give talks.

Tuesdays and Thursdays: The backbone days of AVID, when students get small-group attention from tutors, depending on which course is proving to be the most difficult.

Wednesdays and Fridays: College is the focus, ranging from SAT prep to filling out applications and financial forms.

Before AVID, not that many students from this district in California’s Inland Empire went to college, especially four-year colleges. That changed: “We’re pushing our students toward four-year colleges,” said Lockman. “Last year, we had 150 seniors in the AVID program, and only nine had not gotten accepted to a four-year college.”

Sandy Husk, who oversees AVID nationally, says the key to boosting college success rates lies in energizing both teachers and students. “Not only are students getting academic support, but they’re getting a positive sense of believing in themselves, giving them optimistic visions about how to do better in life.”

Here in Alexandria, it appears that AVID’s positive message has grabbed hold of Berlinda.

“I want to help people to understand that it doesn’t matter if you are poor or rich,” she said. “You can still live a good life.”

Education writer Richard Whitmire’s latest book is The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)