A ‘Precarious’ Moment for Charter Schools in Trump’s Second Term

Despite examples of support from the education department, charter advocates fear Supreme Court case could put their ‘public identity’ in jeopardy.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated May 16

The Trump administration is not only recommending a $60 million bump in funding for charter schools in next year’s budget, Education Secretary Linda McMahon on Friday announced an immediate increase for the same amount — bringing current spending for 2025 to $500 million.

On Thursday, the Education Department also announced a new competitive grant program to help charters share innovative practices more broadly. In a statement, McMahon said the extra funding and new opportunity will “pave the way for more choices, better outcomes, and life-changing opportunities for students and families.”

Earlier this month, the Trump administration proposed a 2026 budget with a $60 million boost for charter schools — the first increase since 2019.

But the welcome news for the sector came just two days after the administration took center stage in an Oklahoma case before the U.S. Supreme Court that questions whether charters are private and can therefore explicitly teach religion. Advocates fear the outcome could disrupt education for roughly 4 million charter school students across the country.

The cognitive dissonance wasn’t lost on Naomi Shelton, CEO of the National Charter Collaborative, which advocates for minority-led charter schools.

The funding increase “signals that this administration sees the value of charters in the broader education landscape. But the progress is tempered by real concerns,” she said. The additional funds won’t matter “if charter schools lose their public identity.”

The request comes as GOP leaders in both the House and the Senate plan to dedicate hearings this week to accomplishments in the charter sector. Trump is recommending $500 million, a 13.6% increase, for the federal Charter School Program, which provides start-up funds for new schools and helps networks grow. The increase stands in sharp contrast to the $12 billion in proposed cuts to other education programs that Education Secretary Linda McMahon said are “not driving improved student outcomes.”

Charter schools, according to the budget summary, have “a proven track record of improving students’ academic achievement and giving parents more choice in the education of their children.” After four years of what one conservative called a “bizarre attack” on the sector during the Biden administration, charter advocates are celebrating the change in tone.

“It is a proof point that the president and his administration believe in charter schools and the need for them,” said Caroline Roemer, executive director of the Louisiana Association of Public Charter Schools.

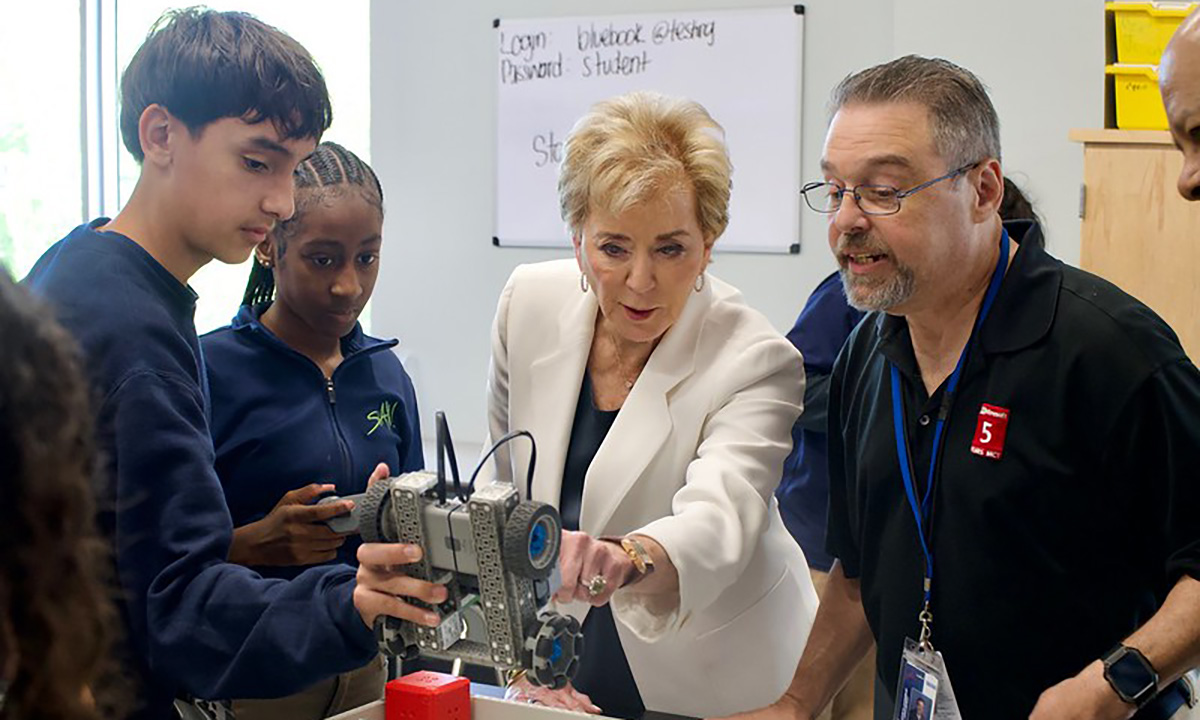

In her two months in office, McMahon has also promoted charters by visiting at least eight of them in New York, Florida, Nevada and Arizona. They include a classical academy that rejects diversity, equity and inclusion programs and a school with a sports management theme in Miami. She has not yet visited any traditional district schools.

“A great wrap in Florida today at Pineapple Cove Classical Academy — another student-centered charter school that is seeing real results,” she posted in March on X after touring three charters and a private Jewish school.

Her predecessor, Miguel Cardona, a former principal and state chief from Connecticut, championed traditional schools. Despite longtime support for charters among Democrats, Cardona recommended a spending cut to the Charter Schools Program and sought to clamp down on charters’ ability to lure students away from district schools.

In 2022, the department issued a controversial package of new rules that called on charter schools to partner with districts, increase racial and socioeconomic diversity and report any business dealings with for-profit companies.

The administration said the changes would increase accountability and transparency in an industry that has experienced some high-profile financial scandals. Some critics consider the federal program an example of the waste, fraud and abuse that Trump and Elon Musk aim to eliminate.

Carol Corbett Burris, executive director of the Network for Public Education, pointed to a 2022 report from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of the Inspector General finding that between 2013 and 2016, states and charter operators that received program funds opened or expanded just half of the schools they planned.

“Hundreds of millions have gone to schools that never opened or closed even before their grants ended,” Burris said. “If the President is serious about eliminating waste and fraud, the CSP is a good place to start.”

But charter advocates say there are too many restrictions on how to use the funds. They can’t, for example, spend the money on facility costs, which Roemer called “one of our toughest barriers to break through.”

Shelton added that in some states, charter authorizers are more likely to favor large networks of schools over independent operators.

“The funding may never reach the communities that need it most,” she said.

Cardona’s revisions to the program, they argued, made it even harder for standalone charters and small networks in urban communities predominantly serving Black and Hispanic students to secure grant funds.

Their advocacy led the department to retreat from some of the rules. But what remained was still “onerous, burdensome” said Jed Wallace, who blogs about charter school issues. Grantees, for example, still had to submit a “needs analysis” and explain how their school would impact the diversity of district schools. Then in January, the department issued applications for funding just before the presidential transition, which Wallace called “one last parting shot” from the Biden administration.

In February, Trump’s education department not only withdrew the application, but removed the remaining Biden-era requirements. On May 8, the department reopened the application window for two grants — one for state agencies and another for facilities. A separate application for charter management organizations is yet to come. The department is expected to judge submissions based on whether they fit the Trump administration’s agenda. That would mean, for example, charter schools couldn’t spend grant funds on diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

Starlee Coleman, CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, said the department also took a lot of the organization’s recommendations, like allowing states to seek waivers from some of the federal rules.

“When you wrap it all up, they’re making some really helpful moves on charter policy,” she said.

A ‘precarious’ situation

But the same administration that plans to streamline and accelerate the grant application process argued before the Supreme Court that the federal program itself violates the First Amendment’s Free Exercise clause because it requires schools to be nonsectarian.

Oklahoma’s St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, which aims to become the first religious charter school in the nation, says because of its Catholic faith, it would not extend the same civil rights to students with disabilities or LGBTQ students that they would receive in public schools. During oral arguments, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson explored how that argument would impact the Charter Schools Program.

“The portion of the federal law that indicates that to qualify as a charter school you have to be nonsectarian in your programs — you’re saying there is a constitutional problem with that or at least there has to be a free exercise exception?” she asked U.S. Solicitor General John Sauer. “Is that right?”

Sauer answered, “Exactly.”

That means if the court allows religious charter schools, they could discriminate in admissions and hiring decisions even while receiving public funds.

“The most obvious group to be targeted would be LGBTQ+ students and students with unpopular religious, or non-religious, beliefs,” said Kevin Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of California, Boulder. But he thinks some religious schools would also turn away students with gay parents, pregnant teens or students with single moms.

The St. Isidore case puts charters in a “precarious” situation, he said. A ruling in favor of the Catholic school could further erode support for charter schools in blue states where they have enjoyed “political goodwill” among Democrats. “It’s easy to understand why national advocates for charter schools would be worried.”

Democratic-controlled legislatures could use a ruling in favor of St. Isidore to repeal their charter laws, experts say. In red states with vouchers, Welner added, there wouldn’t be much to distinguish religious charter schools from other faith-based private schools serving students with state funds.

States could amend legislation to bring charters under more government control.

“But that might be a tough pill to swallow for charter advocates who have long lobbied for more and more deregulation,” Welner said.

Charter leaders’ concerns aren’t limited to the case. Myrna Castrejón, president and CEO of the California Charter Schools Association, called this moment “a mixed bag.”

While she’s pleased with the prospect of more money and hopes it comes with greater flexibility, she’s just as disappointed with some of Trump’s proposed cuts as other public school advocates. After all, under current state laws, charter schools are public and receive the same per-pupil funding as district schools.

Trump would eliminate $890 million for English learners and more than $1.5 billion to better prepare low-income and minority students for college. In a statement, McMahon said the proposal “reflects funding levels for an agency that is responsibly winding down.”

The budget preview also states that the administration would roll 18 K-12 programs into a single $2 billion grant “designed to reduce [the agency’s] influence on schools and students and reduce bureaucracy.”

While the administration said it would “preserve” Title I for low-income students, the recommended consolidation would result in a $4.5 billion reduction for schools. “There is no way we are shielded from those changes,” Castrejón said. “We ultimately serve exactly the same kids.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)