It was just after 6 a.m. when Lovelie Bernard decided she didn’t want to go to school anymore.

The high schooler worked a six-hour shift at the airport every day after school to pay the rent, sometimes doing her homework standing up on the bus or train. That evening, her commute was delayed, and instead of arriving home at 2 a.m., as usual, it was 6 a.m. by the time she unlocked her front door. In three hours, her school, Phoenix Charter Academy in Chelsea, Massachusetts, would start.

After 24 hours without sleep, Bernard arrived at school and passed her principal, Kevin Dean. She didn’t tell him she was thinking about quitting. But he seemed to read her mind.

“He said, ‘I would love to see you graduate.’ That made me cry, because no one in my family has told me that. They want me to work and make money,” she said. “I’m not going to give up. I have someone who believes in me.”

Bernard is 22 years old, the

maximum age for receiving a free education in Massachusetts.

She is also what some refer to as overaged and undercredited — older than most high school students but without enough credits to graduate. Some of these students are dropouts, financially supporting themselves or their families. Some of them, like Bernard — who moved to the U.S. two years ago from Haiti looking to study nursing — are immigrants, arriving with limited English but great hopes of changing their lives.

“Our world needs these people”

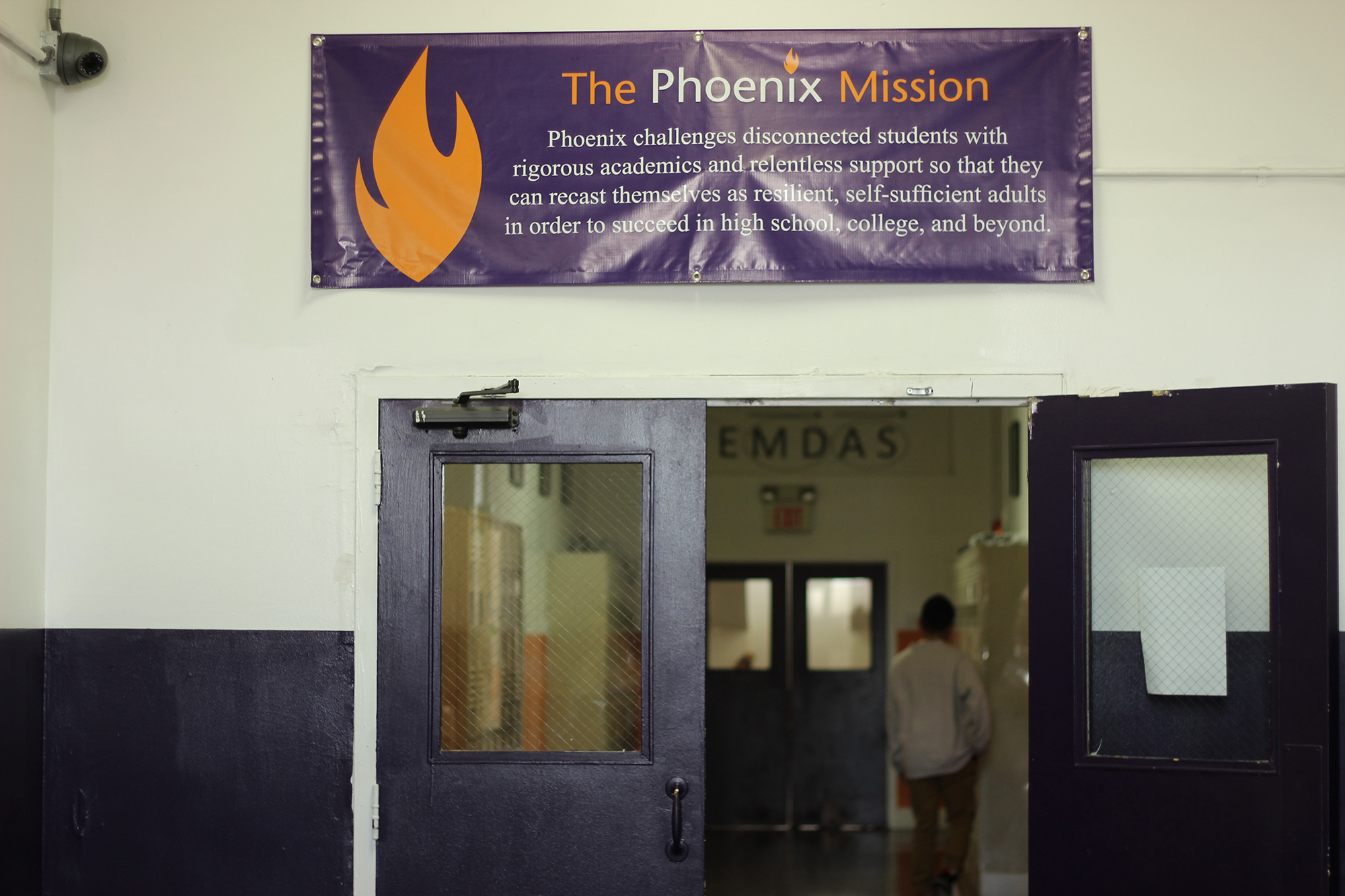

How should the public school system serve these students? That’s a question Beth Anderson has been trying to answer for 11 years, since she opened the first of three Phoenix Charter Academy high schools in the state. Anderson, who has worked with disadvantaged youth throughout her career, was frustrated by the limited options for educational achievement presented to her students.

“Our world needs these people,” she said. “They are incredible problem solvers. They are deeply resilient. They are amazing human beings that we actually need to have in leadership positions in communities.”

So Anderson set out to create a supportive school environment that could build these leaders, giving students who had left the system an opportunity to earn a diploma — along with an aggressive push toward higher education. But with that population come challenges: Of the nearly 500 students Phoenix serves, half are former dropouts, a third are English language learners, a quarter are special education students, and a quarter are over age 19.

The network — whose 2005 state charter charges Phoenix with becoming “a model for alternative education” — has some of the only high schools in Massachusetts that accept applicants through age 21 and allows them to continue their education for free long after state funding runs out at age 22 (14 of the network’s 186 graduates have been over age 21). Once students enter the network, it can take them two to five years to graduate, depending on how many credits they have.

Phoenix is upfront with students that it is not a place for simple credit recovery so they can graduate; they are required to apply to college.

But the model is not serving as many students as Anderson had hoped. The current graduation rate is 30 percent, clearly a low number, though a common one among alternative schools working with similar populations, said Sandy Addis, director of the National Dropout Prevention Center/Network at Clemson University. “We have kids that already have problematic circumstances and have dropped out once and are likely to do it again,” Addis said. “Just because the child has come back doesn’t mean the circumstances are likely to go away.”

So, like the school’s namesake, Anderson is leading Phoenix toward a transformation by analyzing how its model can serve more students, including a personal goal for Anderson of improving the graduation rate to 60 percent. To that end, Phoenix recently received $150,000 through the Barr Foundation’s “Doing high school differently” initiative. The money will be used at Chelsea, Phoenix’s flagship school, as a one-year planning grant, with plans to eventually expand the work to its two other Massachusetts schools.

“If we’re not doing anything to break cyclical patterns … then we can’t complain when particular populations are struggling”

First up for Phoenix Chelsea is relocating its campus onto Bunker Hill Community College this autumn as part of a new partnership between the college and the high school that will connect more students to higher education.

The network is also rethinking school structure and assessments to better serve its students, many of whom are not only behind in credits or don’t speak English well, but work after school to support themselves, parents, grandparents, or children. Phoenix is moving toward mastery-based portfolios, which evaluate students on projects like debates, research papers, or seminars, rather than relying solely on exams. That way, a student who is court-involved, misses school for work, or needs to take care of family members can still complete assignments and earn credits without being penalized for erratic attendance.

“What we’ve realized is that our model is not getting enough kids through, and so we want to actually double down and see if we can double the amount of kids that get through our program at the same standard,” Anderson said.

‘Not going to let you down’

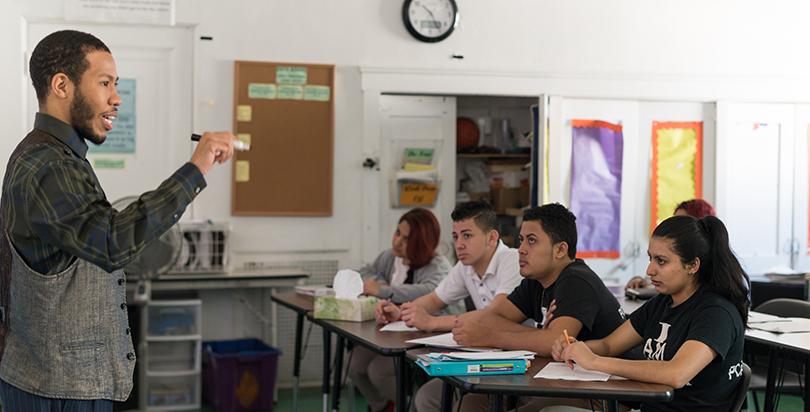

Though Phoenix is re-evaluating its model, its operations are already vastly different from those at traditional schools.

Instead of dividing students into freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior classes, Phoenix groups them into categories. This gives the school the flexibility to place students based on the courses or standardized tests they still need. It also keeps the students from getting discouraged by being placed in a hierarchy of grades that failed them before and are designed for much younger teenagers, said Dean, the principal.

Phoenix students are required to apply for college and can get help from the school in finding financial aid. Remedial courses are discouraged; graduates are expected to take only credit-bearing classes in college, so if they place into remedial math or English on their entrance exam, Phoenix supports them in retaking the test until they can start in entry-level courses.

Phoenix has a day care center inside the building so students with children can still attend school, and there are social workers on site. Educators are in constant communication about their students and have a goal of making 10 calls a week to students or their families.

The daycare inside Phoenix serves both students' and teachers' children.

Photo: Phoenix Charter Academy

For math teacher Sarah Richmond, who is in her fifth year as a teacher at Phoenix, the job involves much more than getting her classes up to speed on algebra or geometry. Richmond has her students’ cell phone numbers, and she’s constantly texting or calling to check in, sometimes driving to their houses to pick them up for school. Sometimes the students don’t respond. Sometimes it feels like nagging. But she keeps at it.

“We try to model as adults, ‘I’m someone who is not going to let you down. You’ve been let down by so many other people in your past, and let me show you that you can have faith in me as a teacher,’ ” she said.

Richmond said she’s inspired by her students’ stamina as they hold down jobs, do their homework, and take care of children every day. Her child attends the same day care as her students’ kids. “I tell them all the time, I can’t believe they are able to do this, to be a mom, to be a full-time student, to work and pay for things and be 17,” Richmond said. “They’re so inspirational.”

But she wants to see more support across the U.S. for students like hers, many of whom want to improve their lives but have limited options.

“We should be sending those students to school, because those are the hardest-working students I see,” Richmond said. “They came here to better their lives, and they hit a roadblock when they’re trying to go to college.”

The network reports that 100 percent of its graduates are accepted into college, 79 percent enroll, and 75 percent persist over two semesters.

A chance to break the cycle

By pushing students toward college, Phoenix hopes it can fill a gap in what its staffers see as limited opportunities for students who’ve struggled to stay in school.

“If we’re not doing anything to break cyclical patterns … then we can’t complain when particular populations are struggling because we’re not investing in a particular or progressive way,” Dean said. “A 20-year-old young male wants to go back to school — that is an incredible opportunity for that person not only to advance their life and success, but to be a real community leader and start breaking the cycle of poverty.”

Nationwide, the number of high school dropouts — defined as 16-to-24-year-olds who are not enrolled in high school and have not earned a diploma — has

decreased over the years, from 10.9 percent in 2000 to 5.9 percent in 2015. But dropouts are disproportionately Hispanic and black, with rates of 9.2 and 6.5 percent, respectively, compared with 4.6 percent for white students, the

NCES reports.

It helps if states reward schools for trying to recover dropouts, Addis said. Traditionally, laws have not incentivized this, holding high schools accountable only for the students they graduate in four years. But Addis said states are also beginning to measure five- or six-year graduation rates, which he said could improve dropout recovery efforts.

Workers with a GED or diploma can earn a median income of $27,869, versus $19,954 for high school dropouts, according to

Census Bureau 2014 inflation-adjusted numbers. A bachelor’s degree boosts those earnings to $50,515. The calculated cost of a high school dropout on the economy is $250,000, including welfare, health care, criminal activity, and reduced contributions to the tax base, according to the

NCES.

For Malik Andrews, 22, the decision to drop out of school at age 16 came naturally when his grandmother was sick and someone needed to take care of her while his mom worked. As he spent his days making his grandmother’s meals and monitoring her breathing, she would ask Andrews why he wasn’t in school. He would lie and say he had already graduated.

After his grandmother passed away, he wanted to return to school, Andrews said, but his public school warned him that he wouldn’t be able to finish before he turned 22. Then his mom heard about Phoenix Chelsea, and Andrews signed up. He likes that Phoenix is a place where students are expected to work hard: “If you’re trying to do what you have to do … and you want a successful future, this is the place for you,” he said.

Andrews is excelling at English but said he struggles with math. He wants to be a lawyer.

“[I want to] make everybody eat their words — people who think I can’t do this or society that tries to label me as something,” he said. “I try to go against the odds.”

;)