A Low-Stress Cure for Overparenting That’s Good for Parent and Child: Letting Your Kids Travel Independently

Helicopter parenting may seem like a faddish term that applies only to those who would do their child’s homework or sit out a detention on their behalf, but the rise of what psychologists call “overparenting” has become so pervasive that education experts have labeled it a crisis.

While researchers and commentators tend to be aligned on its ills, few have identified strategies to help parents overcome the inclination — and even social pressure — to hover over one’s child.

Well-intentioned parents want their children to be prepared for adulthood but, for many, their efforts to help prepare their children are sometimes so invasive that their children end up just the opposite: unable to manage their own affairs. Many parents struggle to repress their inclination to shield children from the pain of making mistakes and experiencing life as it really happens.

It is a challenge that may be exacerbated by the stress of sending children away, whether on school travel, for educational programs or off to camp — trips which are, in many cases, a child’s first without parents in tow.

It turns out that that fear-inducing first trip alone may be a learning experience not only for children but for parents as well. Giving children the chance to travel with responsible adults other than their own parent, a model that study abroad opportunities often provide through schools, offers an early opportunity for parents to work on their own independence from their children, developing habits that will help them worry less and let their students grow.

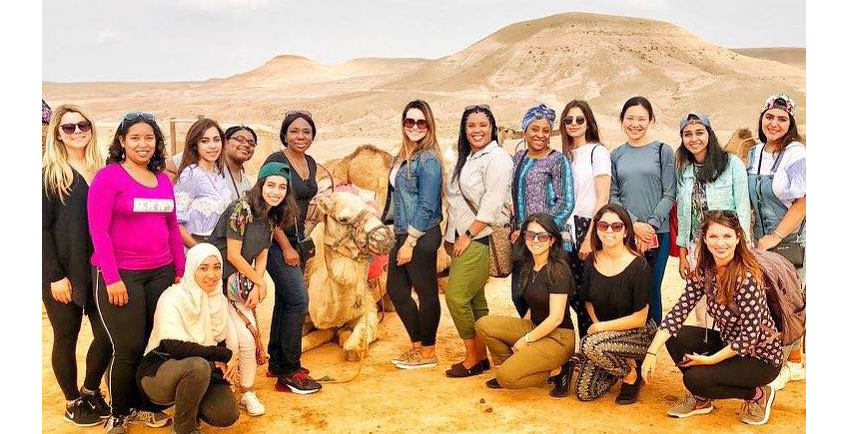

Because they are carefully curated and chaperoned, group travel experiences can provide opportunities for students to build skills they may not otherwise develop while being subject to intrusive parenting. School trips and other forms of educational travel present a unique chance for students to tap into a broader network of adults and peers beyond their parents and families.

Managing the urge to over-parent starts with unpacking the fears and anxieties that can lead to helicoptering in the first place. Parents will, after all, instinctively want to intervene when they think their children are in trouble or uncomfortable. The challenge is making the right judgment about what constitutes a real threat, and what might be an important learning opportunity.

A team of researchers in Ohio recently published a study that provides specific metrics for understanding what over-parenting really is. They describe three essential elements: seeking to know a child’s every move, stepping in before a child can experience failure, and reducing a child’s access to self-directed activities. The researchers go on to demonstrate that excesses in each of these domains lead to exceptionally negative consequences for kids — and for those same kids as they become adults.

When those judgments skew too far toward blocking such opportunities, children suffer. A 2017 study suggested that helicopter parenting may increase anxiety and stress in children. Another study found that children of helicopter parents are unable to manage their emotions. Having overly involved parents can lead to depression, narcissism and academic problems. Parents who develop the tendency to over-parent early seem to continue to engage in intrusive behavior well into their children’s adult years — from college admissions efforts to graduate school coursework.

Trusting children to travel and explore unaccompanied by their parents can help parents practice reversing the key helicoptering behaviors described above. Parents can work on getting comfortable with less information and fewer details, becoming comfortable with what they receive from their trip provider and accepting that cell phone and email access may be limited. They should try to avoid intervention, keeping in mind that while their child may have new and unfamiliar, even somewhat difficult experiences, they should still let their child practice navigating those challenges alone.

And they can get comfortable with allowing their children the autonomy to play a major role in selecting and applying for travel programs. Perhaps most importantly, parents can practice encouraging their children to ask good questions to better understand how to prepare for and learn about the culture and land they’re visiting.

While helicoptering may be a symptom of a broader desire on the part of well-meaning parents to provide for and protect their children, its effects are robbing children of the essential skills they need. In many cases, students may really need help, but they must learn to find it from sources other than their parents.

In the recesses of their first forays into independence, students grow a network of support, they identify additional problem-solving channels, and they recognize within themselves the capacity to manage and master moments when they need help. Building those strategies in a safe environment should put both students’ and parents’ mind at ease.

Dr. Wendy Amato, Ph.D., is a former teacher, administrator and professor of curriculum, and now serves as chief academic officer at WorldStrides, where she oversees the instructional content of educational travel programs across the world.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)