Boston, Mass.

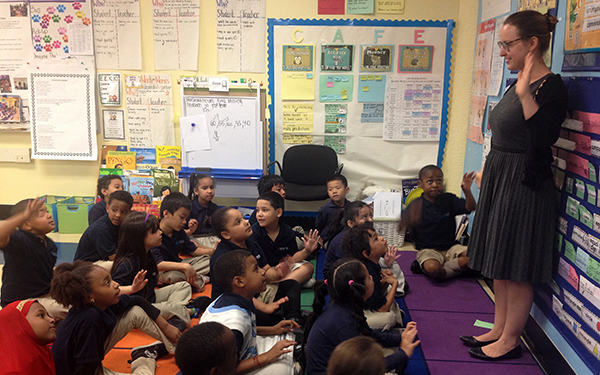

Math class is almost over for Sofia Wilson’s first-graders at UP Academy Dorchester and all eyes are fixed on the confounding blank spot on the whiteboard:

60, 55, __ , 45, 40

Wilson surmises that most of her students have been stumped finding patterns in sequences of descending numbers. So the 26-year-old teacher hands a problem over to Juan Aguilar to figure out and enlighten the class.

He struggles quietly at first but then notices that the numbers are separated by intervals of five and are trending downward. As Juan confidently explains why the answer is 50, his classmates burst with energy.

“Can we give our gritty mathematician a round of applause?” Wilson says.

In this room — and every classroom at UP Academy Dorchester — breakthroughs in learning are cause for celebration. The K-6 charter school in a tough Boston neighborhood best known for spawning the Wahlburg brothers ranked first in the state last year for single-biggest growth in student math scores at an elementary school. The share of kids considered proficient in math increased from 13 percent to 60 percent, while its share of students who achieved proficiency on the English language arts test jumped 26 percentage points.

Marked test score gains have become something of a calling card for high-performing charter schools. What’s different about the UP Education Network is that rather than starting new schools that share geography with the public school district, it takes over failing schools within the public school system and turns them around. Same school building, same kids and the same teachers union, if not the same staff.

UP’s approach stands out in an era when charter schools are often accused of busting unions and cherry picking students.

“No matter how a school is doing today, if you are able to create an environment that is really conducive to learning (students can achieve), ” said UP Network founder Scott Given.

A different kind of charter

UP Education Network began with a career change. In 2003, Given left his job as a consultant to teach history at Boston Collegiate Charter School. Two years later, he became principal of Excel Academy Charter School. He spent three years leading Excel and saw firsthand how a low-performing school could rapidly improve.

Given went from principal to student in 2008 when he entered Harvard Business School. It was there that he started to seriously plan UP.

“Part of the motivation to start UP was seeing the wall that existed between the charter sector and the district sector in Boston and elsewhere,” he said.

Given, 35, wanted to tear that wall down but in 2009, he didn’t think the Boston political climate would welcome the kind of organization he was hoping to develop. So instead, he visited other cities, including New Haven, Chicago and Philadelphia to find a place where he could seed his turnaround dream.

Then the next year, Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick signed an education reform bill, one that helped bolster the charter sector and targeted struggling schools.

Under Massachusetts law, the state can take over a school — or an entire school district — and turn it over to a school operator such as UP for a complete restart. Local school districts can also turn over low-performing schools to groups such as UP.

So far, the state and local districts have handed five failing schools in Boston and Lawrence to the UP Education Network for a turnaround. A sixth is being planned for Springfield.

Sofia Wilson teaches math to her class of first graders. (Photo by Naomi Nix)

How it works

Schools that are taken over by UP largely rely on the public school’s existing funding sources, sometimes supplemented by philanthropy. UP Education Network keeps the same students through the school district’s existing enrollment process.

As part of the re-launch process, educators from the old school are asked to reapply for jobs at UP schools. While all teachers in UP Education Network stay in their respective teachers unions, state or local school districts allow the organization to have more flexibility than the traditional teachers contract would.

At UP schools, teachers also work a longer school day and school year. Once a week, school goes for half-a-day to give teachers time for planning and professional development. The school year starts in August.

“There is almost an extra month of preparation time,” Given said. “That time is so vital to ensuring that our schools do best by students.”

Other aspects of the UP model include pairing character education with a data-driven academic curriculum.

Since its founding, the UP Education Network has seen student proficiency rates rise at all of its schools for which data is available. Last year, median student growth percentiles, which measure how much a student improves compared to other students with similar test scores, were above average at UP schools in most cases.

“The results initially have been quite impressive, which is why we have utilized (UP) in multiple places,” said Cliff Chuang, an associate commissioner in the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. “Thus far the early returns…have been very, very strong.”

UP is tackling one of the most challenging areas in the education reform movement — turnaround. Federal programs incentivize school districts to take actions to reform low-performing schools by awarding grants when states follow certain turnaround models, which often include replacing principals and teachers.

But a recent research brief released by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences claims that while more than 80 percent of states considered reversing struggling schools a priority, at least half of them found it to be “very difficult.”

A school is reborn

Principal Lana Ewing began plotting the academic revival of the former Marshall Elementary School about a year before the school reopened as UP Academy Dorchester. Ewing received leadership training from the network and then began to chart the new school’s academic and cultural foundation.

One of the most important steps, Ewing said, was to recruit top-notch educators. About 2,000 people applied for more than 80 positions.

She also began holding meetings with former Marshall Elementary School parents and others to explain UP’s philosophy.

At UP Academy Dorchester, students are taught the concept of TIGER: Teamwork, Integrity, Grit, Engagement and Respect. Fifth-grade teacher Drew Gallagher ended a June class by asking his students to discuss how their behavior matched the school’s principles.

His students made their case. They were gritty because they kept studying their texts, they showed teamwork by talking about class material among themselves. In the end, Gallagher decided the class earned the T, G, E, and R.

Students are also encouraged to keep track of their own progress towards meeting the academic standards embraced by UP Academy Dorchester.

“I like that when you read you get to read really, really hard books,” second-grader Jaleel Bates said. “My favorite chapter book is Harry Potter.”

In classrooms, students’ progress towards those goals is neatly displayed on the walls. Kids in Wilson’s class each have a paper airplane matched to a Latin American country, which represents their reading level. As their reading improves, their plane inches its way to another nation.

“They get really excited when they get to move their plane,” Wilson says.

Maytee Pená, whose two children have been attending the school since its days as Marshall Elementary, said she was skeptical at first about the UP takeover. Her 10-year-old son was quiet and struggled at times, she said, even having to repeat the second grade.

Today, she sees progress.

“They gave him extra support,” she said. “Now, I know he is getting all the help he needed in the past.”

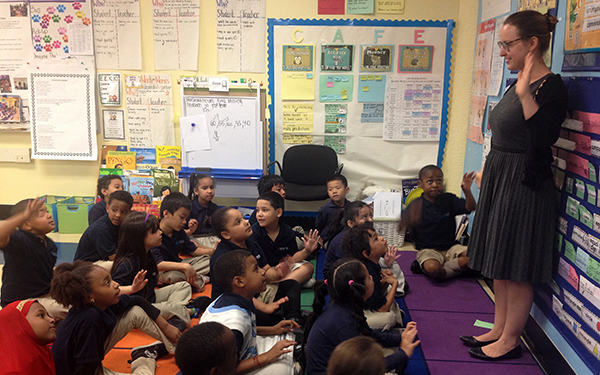

Student Lia Mateo with her teacher, Brianne Gore. (Photo by Naomi Nix)

Bold five-year plan

The UP Education Network continues to evolve. This year, its Dorchester school basked in the national spotlight when third-grade teacher Nicole Bollerman was featured on “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” after deciding to donate a $150,000 prize she won from Capital One’s #WISHFOROTHERS competition back to the school. In her entry, Bollerman said she wished each of her kids could take home a book over winter break. To reward her generosity, DeGeneres surprised Bollerman with $25,000 and gave each of the school’s teachers $500 Target gift cards.

Given said he expects the organization to expand to up to 20 schools serving about 10,000 students by 2020.

The schools are also overhauling their internal assessments to become more rigorous and more in line with the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers exam, or PARCC, a test based on Common Core standards that may soon be fully implemented in Massachusetts.

The network also plans to double down on improving its programming, including principal training, Given said.

“Fifteen thousand students within K-8 who are in Massachusetts are attending a school that is chronically underperforming,” Given said. “We want to be an organization that does something big about that issue.”

“Underperforming” is one label Wilson’s students are looking to shed. After she tells the class that second-graders should be able to count by 2,5 and 10, they set out — using teamwork and grit — to prove they could do just that.

“2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12,” they begin to chant in unison.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)