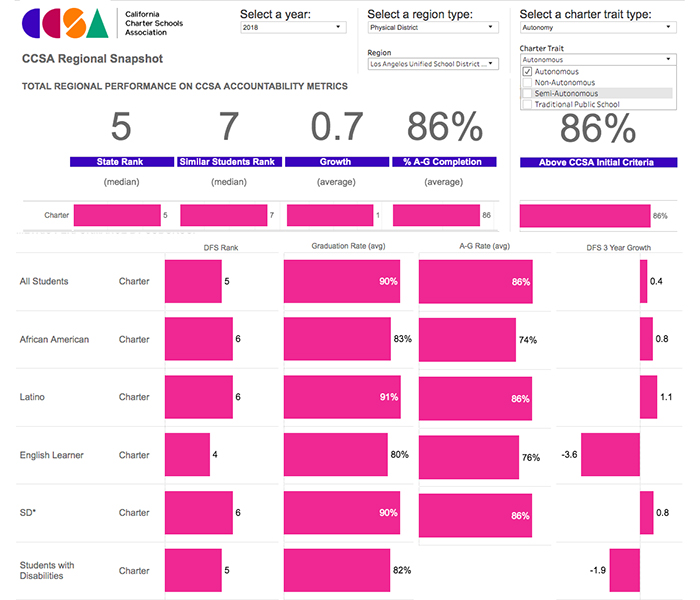

86% of Charter School Graduates in Los Angeles Are Eligible for State Universities — Two Dozen Points Higher Than Grads at Traditional LAUSD Schools

Eighty-six percent of independent charter school graduates in L.A. met college eligibility standards for the state’s public universities last year, according to data from the California Charter Schools Association — 24 percentage points higher than L.A. Unified reported for its traditional schools.

About 8,400 independent charter school students graduated with C’s or better in their college prep “A-G” courses — what students need to apply to the University of California and California State University systems. CCSA’s data cover independent charters authorized within the boundaries of L.A. Unified.

L.A. Unified, comparatively, reported a significantly lower rate in 2018: Nearly 62 percent of about 27,400 graduates passed with C’s. The data include six affiliated charter high schools, which are operated by L.A. Unified. The district’s A-G rate is even lower when considering an entire class, rather than just graduates. LA School Report last month reported that 49 percent of L.A. Unified’s class of 2019 is projected to graduate eligible to apply to the UC/CSU systems.

CCSA and the district record their A-G data differently, complicating direct comparisons. CCSA had the most complete data set for independent charters, whereas L.A. Unified could not provide the A-G rate for those schools. The district does “not have access to this info” because these charters “report their own data to the state,” a spokeswoman wrote in an email.

Traditional schools and independent charters in L.A. are both part of the public school system, and they have comparable student demographics. In both systems, about 4 in 5 students are minorities from low-income families — and some would be first-time college-goers.

Elizabeth Robitaille, CCSA’s senior vice president of school performance, development and support, attributed the gap in part to charters’ laser-like focus on college preparation.

“Many charter schools are beginning their model with a college-going culture and mission that’s specifically saying, ‘College for all,’ not ‘College for some,’” Robitaille said.

Independent charter schools in L.A. have become a political lightning rod — especially in the wake of January’s teacher strike, which tied traditional schools’ plight to charter schools’ expansion. The state legislature is reviewing four bills to restrict charters, including one that would eliminate a current state law provision that “increases in pupil academic achievement for all groups of pupils” must be the most important factor in deciding whether to renew a charter. The bills would also end charter schools’ ability to appeal to the county and state if a district rejects their application and would cap the number of charters in the state.

CCSA and charter school leaders spoke with LA School Report about what is factoring into the higher numbers. Here are some of the main examples:

1 Traditional schools and independent charters can have different graduation requirements.

L.A. Unified requires D’s or better in A-G courses to graduate, even though the UC/CSU systems require at least C’s.

But many independent charter high schools — 55 of 77 authorized by L.A. Unified, for example — require C’s or better to graduate, according to the district. (Independent charters within L.A. Unified’s boundaries can be authorized by the district’s school board or other local entities, such as the L.A. County Office of Education. The district and CCSA couldn’t provide a complete breakdown.)

“All charter schools and districts have to get their A-G coursework approved through the UC system. … But independent charters have autonomy to set their own requirements,” a CCSA spokeswoman wrote in an email. “So when the district decided that a ‘D’ grade counted as passing A-G coursework, that didn’t impact independent charters’ requirements.”

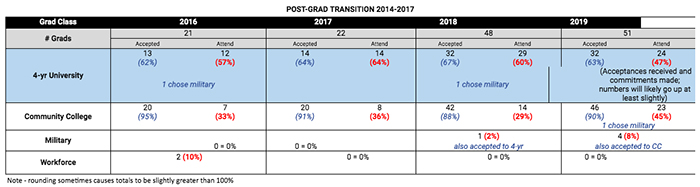

For L.A. charters like North Valley Military Institute College Preparatory Academy, which this spring has 47 of its 51 graduating seniors set to attend two- or four-year colleges, the C-or-better requirement helps guarantee access. “We try to make really clear to everybody who wants to come here that we are about getting kids ready for college,” Superintendent Mark Ryan said. “We want them to have college as an option.”

“We’ve never had D’s at our school, because what’s the point?” said Alfonso Paz, executive director of APEX Academy, which has 390 students in grades 7 to 12. “Our mission is … to stop the cycle of poverty. And when we did all this research, we found that what a kid needs is to be A-G eligible. So we went backwards planning from there.”

The district has been working to expand college access in other ways. L.A. Unified for the first time paid to have all district juniors take the SAT in school in March — a reported $1.2 million cost, according to the L.A. Times. The “Close the Gap by 2023” initiative passed by the school board last June has also set a higher bar for college readiness, aiming to make 100 percent of high school graduates eligible to apply to a state college by 2023.

2 Data are defined differently.

Charter and district data can be higher — or lower — depending on where the data are from and how they are defined.

CCSA’s data showing that 86 percent of charter graduates in 2018 passed their A-G courses with C’s or better, for example, include almost all independent charters authorized within the boundaries of L.A. Unified — including those approved by the L.A. County Office of Education and the state. The data don’t include “dashboard alternative schools” — there are at least three independent charter high schools with this designation — because they are “serving a very high risk” population and are “treated differently” by the state, a CCSA spokeswoman said.

L.A. Unified’s A-G rate actually fared better with CCSA’s data, at 65 percent, versus the 62 percent that the California Department of Education and the district reported. Because CCSA excludes alternative schools in its data analyses while L.A. Unified retains that data, that discrepancy likely caused the percentage bump, the spokeswoman added.

The state education department reported the same district A-G rate as L.A. Unified did. However, it reported a significantly lower charter A-G rate — 74 percent. This is because unlike CCSA’s data, it only counts charters that are authorized by L.A. Unified.

3 Charters have a more prominent ‘college-going culture,’ leaders say.

A college-going culture centers on a “belief system” that “every student can go to college, and that it’s our job to prepare them, and it’s their job to choose,” says Cristina de Jesus, president and CEO of Green Dot Public Schools California, a charter network with nine high schools in L.A. serving nearly 6,100 students. “We don’t make any exceptions around that.”

That belief system, she continued, is established by thoroughly vetting new staff; by taking students on college tours — sometimes as far as New York and Boston (tour funding comes from Green Dot’s fundraising efforts, or from the budget, de Jesus said), and even by something as simple as teachers putting their alma mater and college major on their classroom doors.

Another element is having a lower student-to-counselor ratio. School counselors are integral to students’ success; they help them decide which college is the right fit, guide them through financial aid forms and connect them with mental health resources. The American School Counselor Association recommends a 250:1 ratio, though the national average is 482:1.

At Green Dot, where 69 percent of graduates in 2018 had C’s or better in their A-G courses, the ratio is about 260:1. Every school must also have a full-time psychologist, de Jesus said.

North Valley Military Institute has two counselors, which works out to a 318:1 ratio, Ryan said, with 84 percent of graduates in 2018 getting C’s or better despite a student population that is 25 percent students with disabilities and 8.2 percent students who are homeless. Both percentages are about double the district average for those student groups.

The ratio is notably low at APEX Academy, at 150:1. The school had a 79.3 percent A-G rate in 2018, even though an estimated 75 percent of the student body is battling some form of mental health issue or trauma. It embraces a mental-health-first model that Paz said is all about “meeting students where they’re at.”

“The basis of all change comes from relationships,” Paz said. “That’s why you stay in the system.”

L.A. Unified schools’ ratios, meanwhile, can be nearly triple the ASCA’s recommendation. There can be as few as one counselor for every 690 students in predominantly minority high schools, and as few as one counselor for every 790 students if the school has more diversified enrollment. The district’s traditional schools “have the [freedom] to purchase additional positions,” an L.A. Unified spokeswoman wrote in an email.

• Read more: LAUSD high school counselors say they don’t have enough time to help students with college application process

Traditional schools in California are systemically underfunded; the state ranks anywhere from 22nd to 46th in per-pupil spending, depending on the data source. And charter advocacy organizations do often benefit from philanthropy. But Paz said the lower student-to-counselor ratios at schools like his doesn’t mean a charter has more cash on hand. Rather, he said it’s about how a school prioritizes hiring and retaining counselors when it budgets.

“My budget constraints are the same budget constraints as every school in California. I don’t have a trust fund, I don’t get anything extra,” Paz said. “Has it been hard? Yes. One time we had to dismiss some people. It’s really hard. You need a clear understanding of what you’re doing.”

4 Charters can have lower student-to-teacher ratios.

Across Green Dot’s L.A. high schools, the average student-to-teacher ratio is about 24:1.

Low ratios “allow for more individualized support for students and allow teachers to know their students well,” said de Jesus, ensuring “that every student is truly ‘seen’ in every sense of the word.” Studies show this to be true in the earlier grades in particular.

While state-level data put L.A. Unified’s average high school class size in 2017-18 at about 25 students, the district reports that the current average for “core classes” such as math and English is nearly 40 students for grades 9 and 10 and nearly 43 students for grades 11 and 12. As with counselors, a school site can budget for more teachers, a district spokeswoman confirmed.

Lowering class size was one of the aims of January’s teacher strike and subsequent contract.

5 Charters have more freedom around curriculum.

Independent charters within L.A. Unified’s boundaries — and across California — are public schools. They are not-for-profit and have oversight provisions such as submitting budgets to the county, commissioning third-party financial audits and petitioning for renewal every five years. They are also privately run and abide by their own “charter.” Therefore, they have more discretion around curriculum, the length of the school day and year and hiring and firing.

“The autonomy that charter schools have allows them to develop and make quick adaptations” and “revise and adjust the kinds of interventions and supports they’re giving based on the kids that are there in front of them,” CCSA’s Robitaille said.

6 Charters have detailed academic plans.

Independent charters petitioning to open within L.A. Unified boundaries have to present an academic plan that addresses 15 elements. These range from the needs of the targeted student population to annual performance goals — all of which serve as an educational road map for a charter once it opens, a CCSA spokeswoman said.

Requirements include:

● For proposed high schools: An explanation of how the school program and course schedule will enable all students to meet graduation requirements and A-G requirements within four years.

● Description of the proposed charter school’s annual goals for all pupils and for each subgroup.

● An outline of the specific educational interests, backgrounds or challenges of the student population the school wants to serve.

● Description of the educational program’s overall curricular and instructional design, including how the school will structure and staff the program. Research-based evidence is required to demonstrate how the design will successfully serve the needs of the targeted student population.

Charters’ commitment to these plans is reviewed when they apply for renewal every five years. Affiliated charters also undergo this renewal process. District schools have no similar review and renewal process. However, any schools that receive federal funds through the district must develop a “School Plan for Student Achievement” — reviewed and updated annually — that “includes long-term goals, measurable objectives and a system for evaluating progress toward meeting those goals,” a district spokeswoman wrote in an email.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)