74 Interview: Mary Beth Tinker on Her Landmark Student Speech Victory Central in New SCOTUS Case — And Why Today’s Youth Activism is as Vital as Ever

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Mary Beth Tinker was just 13 years old when she wore a black armband to school and changed America.

As the Vietnam War grew increasingly controversial in the late 1960s, she and several other students from Des Moines, Iowa, wore armbands to class in a plea for peace despite a new school policy that sought to stifle their activism. Suspended for disobeying school orders, her silent protest eventually found its way before the U.S. Supreme Court, where the justices released a landmark 1969 opinion protecting the First Amendment rights of students in public schools.

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the court found that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” and that educators “may not silence student expression just because they dislike it.” But on-campus speech does have its limits, the court found, and educators can punish students for comments that cause a “substantial disruption” to student learning — a threshold known today as the “Tinker standard.”

Half a century later, the Tinker standard will have another day in court on Wednesday. This time, however, justices won’t be weighing the merits of student speech that’s clearly political in nature, such as Tinker’s black armband. Instead, when the court hears oral arguments in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., debate will center on a Pennsylvania teen’s off-campus, expletive-filled Snapchat post.

The outcome could have significant implications for the future of students’ First Amendment rights. Specifically, the court is being asked to consider educators’ authority to regulate student speech outside the schoolhouse gate.

The case centers around a Pennsylvania high school student’s 2017 Snapchat post expressing frustration because she didn’t make the varsity cheerleading team. Upset with her placement on junior varsity, she uploaded a selfie in which she raised her middle finger and wrote in a caption “fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything.” When the post, uploaded on a Saturday, made its way to school, officials suspended her from the junior varsity squad for a year.

School officials said the punishment was necessary to maintain a “teamlike environment” and prevent chaos at school, but the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals found that educators violated her First Amendment rights. Educators lack authority to punish students for off-campus speech, the court found, even if it created a disruption at school.

Ahead of the potentially historic oral arguments, The 74 caught up with Tinker to reflect on the national precedent that her symbolic anti-war protest set for students across the country, and to discuss the implications the Mahanoy case could have for students’ First Amendment rights going forward.

The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Central to the landmark Tinker case, you wore a black armband to class despite a school rule prohibiting you from doing so. Why do you believe that your civil disobedience was so critically important at the time?

Tinker: There was a group of us that wore black armbands that year, and the feelings that we had about the war were so strong and we felt so badly about what was going on there. It’s a feeling that many young people have today about the things going on in the country and in the world. And so, it’s really important for youth and for everyone to express their feelings about the policies of their lives and the world. That’s why I think it was really important for us to be able to express ourselves.

We didn’t realize there was going to be civil disobedience involved. There were 50 kids in the Des Moines schools that had signed up to wear the armbands and then the principal heard about it through the local student newspaper, so then they had this secretive meeting where they made their rule against armbands, and that was only a couple of days before we were planning to wear the black armbands. So that caused kind of a moral dilemma because we didn’t really want to break the rules, but we felt really strongly about it.

The idea of civil disobedience wasn’t really part of the plan until the principals made the rule against the armbands, which did turn out to be kind of ironic because they had allowed other students to wear black armbands to mourn the death of school spirit. But when it came to wearing them to mourn the dead people in Vietnam, then that wasn’t going to be allowed.

Was that rule made because school officials disagreed with your political stance?

Yes, it seemed that the school administrators were willing to allow students’ speech, but they just wanted it to be speech that they agreed with. So that was part of the problem because in our democracy, the government is not allowed to prefer one viewpoint over the other. That’s called viewpoint discrimination.

Decades later, you still remain actively involved in promoting the free speech rights of students. How has your perspective on the importance of student speech changed in that time?

I’ve come to realize that students’ rights are very important for their health. I became a nurse after the ruling in the case, and I started working largely with children and teenagers.

I started as an emergency medical technician, so I worked a lot with trauma and I was taking care of youth in hospital emergency rooms. I started to put together the issue of students’ rights and student well-being and student health. It’s really important for the physical health, the mental health, the social health, spiritual health, all of it, for youth to be able to express themselves. And of course, it’s also very important for society to have the input of youth voices. When a society is one where children and teenagers thrive, it turns out that it’s also a society where it’s better for all age groups.

The landmark opinion in Tinker protected the free speech rights of public school students on campus unless it caused a substantial disruption to the learning environment. Do you believe that’s the right standard today?

Well, that standard was very interesting because it initially came from a case in Mississippi where African-American high school students wore buttons to school in the fall of 1964. The button said “One man, one vote SNCC,” which is the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. They wore those buttons to school because they were protesting murders by the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacists.

Some students wore the buttons to school to protest and they were told they could not do that. So that case started working its way through the court. When it was decided in 1966 after we wore the armbands, the appeals court in Mississippi, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, said that they should have been allowed to wear those buttons. Why? Because they did not substantially disrupt school. That case and that standard was then later cited in the Tinker ruling.

Is it a reasonable standard? I think it’s a reasonable standard but it’s open to interpretation. A student in Arizona a few years ago wore a Black Lives Matter shirt to school for photo day. She was told she couldn’t do that because a white student had argued with her a couple of weeks before then and so the school thought that it would be disruptive. The principal ended up reversing his decision and she was allowed to wear the shirt, but the standard is very much open to interpretation.

Right. What is the definition of ‘substantial?’ That word could be hard to quantify.

Exactly. And the other problem with it is that, according to the Tinker ruling, student speech that the administration can predict will be substantially disruptive could even be censored. There’s something called the heckler’s veto for everyone else out in public. If you say something and someone comes up and starts harassing you for saying that, you are the one whose speech is protected, not the heckler. The heckler is not supposed to be allowed to veto your speech. But in schools, that’s not the case because of this substantial disruption standard.

But to me, considering all of the things that schools are balancing, it’s reasonable at this time.

Your case centered around on-campus speech and the new case that’s before the Supreme Court is about off-campus speech. How do you think that your case applies to off-campus student behavior, and how should the Supreme Court clarify schools’ authority to regulate off-campus student speech?

I think that the Supreme Court should leave the standard the way it is and I think that they should uphold the Third Circuit’s ruling. I was very honored to be speaking with a group of community college students at Philadelphia Community College last month, with Judge Ted McKee from the Third Circuit. He was explaining to all of us how they came to that decision and that they held that the case was clearly within the Tinker framework in that there had been no substantial disruption at all, so I’m hoping that the Supreme Court will agree.

Your speech with the black armbands was clearly political in nature, but the Snapchat post in the new case, arguably, is not. Do you believe that both forms of speech deserve the same level of free speech protections?

Yes, I do because I think that it’s important for students to be able to express themselves. That includes their feelings of frustration, and it even includes them being able to say a commonly used curse word.

And I, again, bring this back to the idea of students’ health and students’ well-being, that it’s really important for all of us to maintain our mental and emotional health. There’s a lot of talk lately about mental health services for teenagers and for youth who are very stressed, especially now with the pandemic. So, I believe that it’s best to promote mental and emotional health and to keep young people healthy instead of waiting until they have problems. Part of young people maintaining their emotional health is being able to express themselves without being punished.

Education groups argue that schools need authority to punish off-campus speech to protect other students from cyberbullying and threats of violence. What is your response to that argument, especially given the facts of this case in particular?

Of course there’s a line to be drawn when it comes to truly threatening speech or bullying, but schools have other ways of dealing with that besides trampling on students’ speech rights. They don’t need to weaken the overall rights of students and to expand the reach of administration to such an extreme degree as some are calling for in this case.

In the last few years, in what key ways have students used their voices to drive tangible change in their communities?

I’ve been following some of the things going on with Black Lives Matter in schools, where students have been calling for and succeeding in having schools address racism. Students are calling for a curriculum that deals with racism.

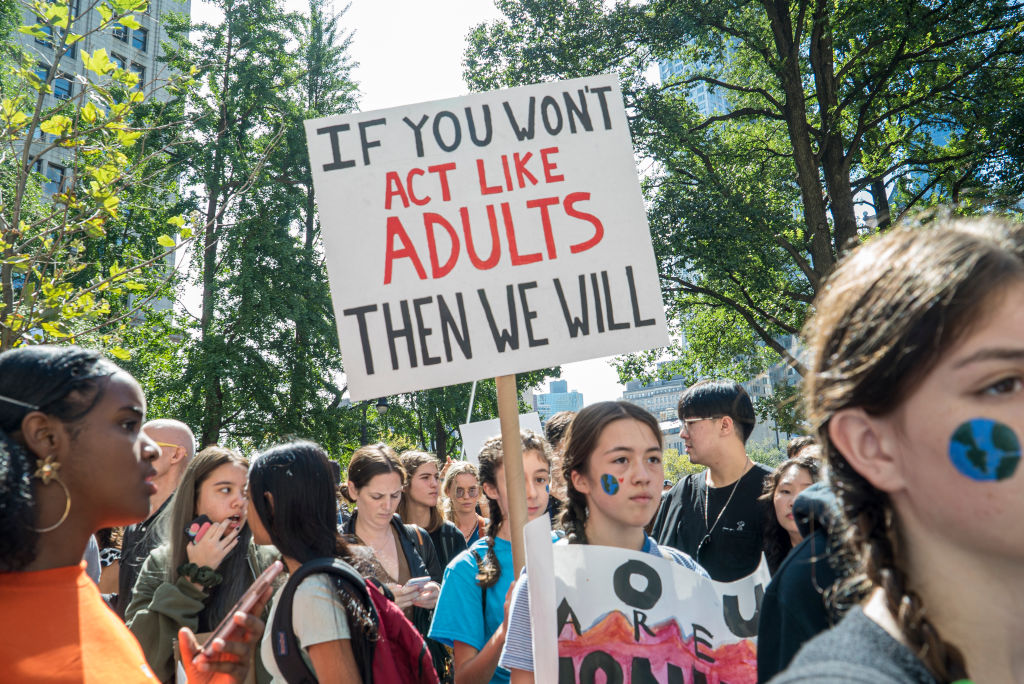

A few years ago in Jefferson County, Colorado, the school board tried to eliminate controversial issues from the social studies program, and students rallied. Thousands of them got out and picketed with signs that said things like ‘We want the truth,’ and that policy was reversed. Students are speaking up about the environment.

A young woman named Destiny in Baltimore found out that a [trash] incinerator was going to be built right next to her school. She rallied all of the students there and succeeded in getting that stopped.

Students in D.C. are speaking up for so many things against gun violence and, of course, that’s been a major movement across the country for young people. students across the country have succeeded in getting better gun laws in their communities. And students across the country are also organizing to reduce the voting age to age 16. There are now three cities in the United States where 16-year-olds can vote.

It’s very heartening to see the efforts that are going on across the country and I’m so honored and privileged to be able to meet with students every week, now virtually, across the country who are speaking about so many things.

Students are for gay rights, students are against gay rights. There are various things that students are speaking up about and they should have the right to discuss and talk about these important issues.

What implications does the new Supreme Court case carry for the future of student speech, from benign social media posts to political protest movements like March For Our Lives?

Well, it’s a chilling effect when students get in trouble for the things that they say outside of school. We need young people to express themselves for their own good and for the good of society, and we need to help guide students toward effective ways to do that and in ways that respect each other. But to just shut down on controversial issues or controversial speech is not the answer. It’s very important to democracy that we have controversy and it’s very important to education.

What advice do you have for the justices? What is the best outcome in this case?

In 2013, the Liberty Institute hosted an event at the Supreme Court as part of the Supreme Court Historical Society with Justice Alito. It was about Tinker v. Des Moines because they’re supportive of the ruling as many conservative people are. It’s not really a partisan issue.

After the program, I went up and talked to Justice Alito and I said, ‘During your Senate confirmation hearing, I heard them ask you about the Tinker ruling and you said that you would uphold it, so I was just wondering if you would uphold the Tinker ruling if it’s challenged?’ He told me ‘Well, I guess I would because I do believe in students’ rights.’ So I’m hoping that the Supreme Court will respect the voices of youth and the importance of youth voices and that they will affirm what the Third District found, that the youth do have a right to express themselves.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)