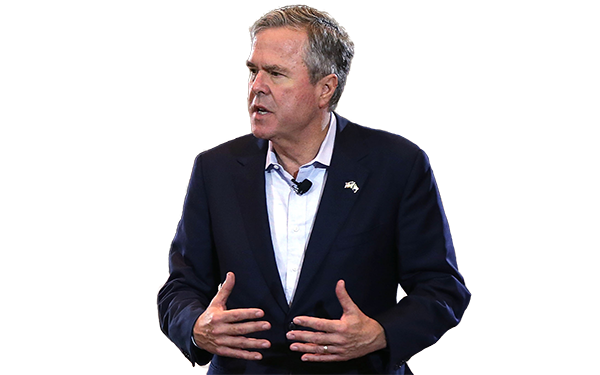

74 Interview: Jeb Bush — Yes on Choice and Standards, No on Trump and Clinton

Former Florida governor Jeb Bush doesn’t believe that either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump will be good for education as president.

He’s not saying whom he’s voting for, however.

He may have given a hint during his keynote address at a midtown education policy event last week sponsored by the Manhattan Institute, a right-of-center think tank.

Bush alluded to a question during an earlier panel about giving education advice if the next president happened to call. (I moderated the panel, which did not include Bush.)

“I want to answer the question, the really good question — I’m not going to get that call, by the way — but if I did get a call several weeks after the election, what would I tell President Johnson? I mean President whoever,” Bush replied, apparently referring to the former New Mexico governor and current Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson, prompting laughter from the audience.

(A spokesperson for Bush said the comment was a joke. The New York Daily News reported that Bush “repeatedly” indicated his support for Johnson during the event. However, Bush’s spokesperson said the former governor hadn’t decided how he will vote.)

“For that candidate who becomes president of the United States, if they called me, I would say, ‘Go back to work with Congress to push as much power and money back into the hands of people … trust people that they love their children with their heart and soul, give them the tools to make informed decisions — and a thousand flowers will bloom,’” Bush said.

Prior to the event, Bush spoke with me about his views on education policy, reiterating long-held positions in support of school choice, standards-based reform and the importance of accountability, and arguing, contrary to some research, that school choice is the best way to address racial and economic segregation.

The entire interview, edited lightly for clarity and length, is below.

Matt Barnum: I wanted to get your thoughts on online charter schools. I know that’s something you’ve advocated for before. But we’ve seen some research recently from—I’m thinking of the Fordham Institute and CREDO, that students who attend those schools get much worse results on standardized tests. Does that concern you?

Jeb Bush: Yeah, it does. Rising student achievement is the only thing that matters; everything else is an input. In Florida we were the first state to allow Connections Academy and K12 to come in, and we were the first state to build and effect our own virtual school that has had extraordinarily good results. You need accountability around all schools.

I find the advocates of the status quo a little hypocritical when they talk about online schools that are run by a private business or a not-for-profit, or charter schools that are for-profit or run in a not-for-profit status. They don’t want to impose the same accountability on traditional public schools. I think every school should have robust accountability. If they don’t work, close them down.

Now that we know that the online charter schools aren’t getting good results—

You’re way too broad in that.

The CREDO study found that in almost every state that they looked at, there were negative findings for online charter schools. That doesn’t mean every single one is bad.

That’s my point.

Every bad school should be shut down, irrespective of the delivery system. The delivery system is not relevant. That’s an input. The outcomes are what matters. I can tell you, in Florida, 400,000 courses are administered by the Florida Virtual School. It’s a way for the state to implement course choice. You can stay in the traditional school or go to a charter school and take an additional A.P. class online. You can take all your classes online if you’re a homeschool student, which I think is important as well because ultimately parents should be making this decision. Where schools that are using the traditional model on an online format and they’re not getting the results, they should be closed. Plain and simple. There should be accountability around every school.

I know this is going to be a tough question for you, but who do you think will be better on education, a President Trump or a President Clinton?

Neither.

Thankfully it’s one of the policy areas, if you’re not passionate about making education reform a national priority, which neither are, then the role of the presidency is — they’re not the chairman of the national school board. They’re not 50 states or where the policy’s made.

Neither are going to be helpful, I don’t think, because it’s not a priority, but that’s OK, because the fight has to be state by state.

Have you decided whom you’re going to vote for for president?

I’m not going to talk about that.

I think ed reform has had a bipartisan coalition for a while, including President Obama’s administration. Do you agree with that, and do you think the coalition has sort of fallen apart?

I think the coalition has eroded, and the bolder and bigger the reforms, the less people coalesce. We’re in this weird era of timidity as it relates to policymaking, not just education. We’ve got infrastructure problems and $2 trillion of cash sitting on corporate balance sheets that can’t come back into the country because we have an antiquated tax code. Or we have $50 trillion of contingent liabilities as it relates to entitlements.

Historically, left-right coalitions have emerged to deal with great challenges of our times, and, unfortunately, whether it’s education or dealing with the social contract or dealing with the lack of social mobility, right now that doesn’t exist to the extent that it’s needed in order to get big stuff done. I think the president played a constructive role early on, but his interests eroded as well — quite natural for a president who has to deal with fighting terrorists. I mean, the president has a huge agenda.

The unions, I think, have more power today inside the Democratic Party than they did four years ago. You have a candidate that was in favor of charter schools until she wasn’t, coincided coincidentally with her run for president. On our side we have people who are almost exclusively focused on the effort to push power back to localities irrespective of reform.

And you see that with Common Core, that’s a perfect example, right?

Not just Common Core.

Common Core, I would argue, wasn’t a federal program.

I’m not quite sure how we restore the center-right, center-left coalition that had in the past been more effective in helping states change their governance models, but it’ll be important to do.

It was stunning how quickly the misinformation spread in right-of-center circles about Common Core, and I think there was also principled opposition to the federal involvement that existed — it obviously didn’t start with the feds.

Without getting into the gory details, the federal government’s involvement was indirect; it wasn’t direct. There is so little trust in America today, both sides of the ideological spectrum about government in general, in retrospect it shouldn’t have been a surprise. But it’s disappointing because it crowds out any discussion about everything else. Higher standards is one of many things that have to happen. By itself — maybe there are people who would say all you’ve got to do is have high standards and be done with it. I mean, we’re going to talk about accountability, how you create a state-driven accountability system, here at the Manhattan Institute, the potential of charter schools playing a role in that. Those discussions have become less relevant in the political realm. Now, they’re still out there in every state capital. The good news is that people actually do care about this stuff.

One thing I don’t think I’ve heard you talk about is segregation in schools. In New York City, our schools are very segregated. Kids of color, black kids, often go to school together without any white kids or affluent kids. Does that concern you? Is there any role for the government to integrate schools?

If we started from scratch and said: Here’s the accountability that we’re going to have. We’re going to make sure that we have rising student achievement, and when it doesn’t happen, we call it out. Moms and dads will know how schools are working, that they have a menu from which they can choose private option, public option, a hybrid, a competency-based model, a magnet school, schools that focus on a thematic kind of learning — whatever it is, if you’d have a menu, and you choose, I don’t think you’d have the same segregation. I’m almost positive.

If you look at Florida — I know more about Florida than other places — our school choice programs have created less segregation rather than more. Rather than allow the monopoly to decide where kids go and make it convenient for them, maybe we should empower people to make that decision and get a better result.

You want to have children have an environment where they’re safe and where there’s high expectations and where there’s rigorous measurement of whether kids are learning or not. To simplify this, a year’s worth of knowledge in a year’s time would kind of be a pretty good objective of spending a year in school. That should be the overall mission. If that’s done in a school where it’s not only segregated but it’s all young Hispanic boys, why not try it?

I just don’t think we have the luxury of being politically correct right now. There’s a thousand kinds of alternatives that ought to exist, but the monopoly and the politics and the bureaucracy stifle the kind of innovation that occurs each and every day in every aspect of our life that is unregulated.

I mean, there is some evidence from a while back that when schools were integrated — and this was forced integration — student achievement for black kids improved dramatically.

Sure, because obviously when we had a totally segregated system it wasn’t separate but equal, it was separate and disastrously unequal. The minute you integrated, you naturally had African-American students, particularly, accessing information that they never had before. In the 21st century, I think the way to bring about rising student achievement is the way I described it, which is customizing the learning experience for the unique needs of the child rather than force-fitting a child into the political agenda of the adults.

I’ve heard you say before that money is not the answer to help schools. But there has been some evidence recently — I’m thinking of a study that was published in Education Next and other places by Kirabo Jackson and Rucker Johnson — that found that when you give schools more money, they actually do improve student outcomes. Has your thinking changed on that at all?

I don’t know what the research was that you just said, but if you’re spending $25,000 a student in Newark and you’re getting worse results for like-kind students than you do spending $8,000 in an urban core Florida public school, I can’t imagine that the research wouldn’t suggest that by itself that money is the answer. We’ve tried it that way. We spend, as a nation, more per student than almost any country in the world and we get abysmal results.

If we cut funding now in Newark, and that’s actually what Governor Christie has proposed, do you think student achievement would go down or stay the same?

I don’t think it’s relevant in the overall objective. If you created an open system that I envision, you would have rising student achievement at far less because the scalability of success would become natural.

A successful school that is spending $8,000 a student, in the system we have today, all across this country, with 13,000-plus government-run, unionized, politicized monopolies, doesn’t take kindly to that success; it doesn’t say, Let me try to steal the ideas that created that success. In fact, those successful schools many times are marginalized. I think isolating money as the answer to this is wrong.

Now, where can money be helpful? This is from a practicing policymaker, not a think tank guy. Funding your reforms first rather than funding the beast, that works. If you want to eliminate social promotion in third grade, you gotta have interventions, so that in second and first and kindergarten and pre-K and in third grade, so that there’s a strategy to make sure that kids aren’t held back. That requires money. Putting the first monies that are appropriated into that makes sense.

If you believe accountability is important and you reward improvement and reward schools that are A-graded, that’s $150 of school recognition money, the largest bonus program in the country for teachers for a job well done. If you didn’t fund that, it would be harder for the reforms to take place. If you want to pay good teachers, great teachers, more, it’s going to work better than not paying them.

Money does matter, but — I hadn’t seen the study you’re referring to — but just, here’s the funding formula, we’re going to put money into it, no accountability, you go do it, and we’re going to spend more money next year. And research suggests you get a better result? I think research would suggest over 50 years we’ve gotten a worse result.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)