6.7% of Students Skip School out of Fear. Worry Over School Shootings Is Up. Yet School Violence Is Down. What Does This Mean?

Moments after she had escaped the high school where a gunman killed 10 of her classmates, a Texas teenager spoke to a TV crew about her experience. The reporter asked if she ever thought this would happen to her. The student gave a shaky laugh. “It’s been happening everywhere,” she said. “I always kind of felt like eventually it was going to happen here, too.”

Her response went viral, perhaps because her words resonated with the fear so many people in the U.S. have around school shootings. One recent survey found that most adults and students are afraid a school shooting will happen in their neighborhood. Another found that parents’ fear for their children’s safety at school has tripled in the past five years. The new national Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that in 2017, 6.7 percent of students reported they missed class in the previous month because they felt unsafe at school — an increase from 4.4 percent from 1993, but not a significant change, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

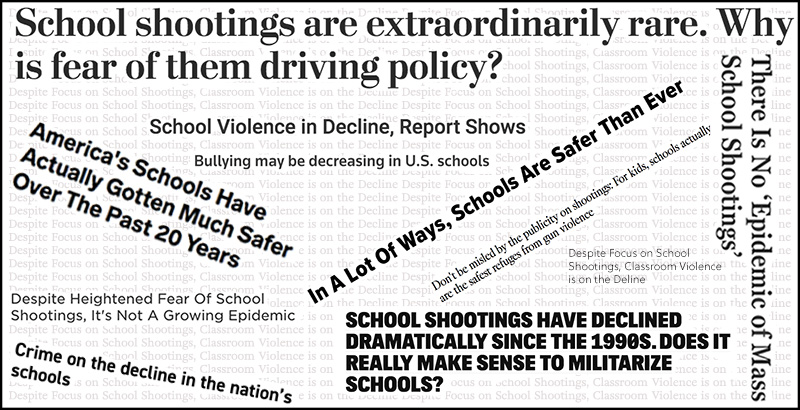

But in reality, researchers say, school shootings are rare and their numbers are not increasing. Schools are safer than they’ve ever been, and violence and bullying have decreased over the past 20 years, according to federal data. Every year, more than 1,100 school-age children are killed — but only 1 percent of them are killed at school.

Researchers point to increased media coverage of school shootings as the reason for this exacerbated fear. But they are divided on whether the fear is detrimental or useful. Some argue that public awareness has led to a decrease in school violence. But others point out that it has also led to zero-tolerance policies that suspend or expel students, especially children of color.

In a March meeting with the National Prevention Science Coalition in Washington, D.C., University of Virginia professor Dewey Cornell argued that this outsize fear could cause more harm than good:

“Our decisions about school safety have to be based on a careful analysis of the facts and not just be driven by fears and emotions, however important they are,” he said. “And to recognize that school violence is a small part of a much larger problem of gun violence.”

Districts have spent billions of dollars on “hardening” measures such as metal detectors, security guards, surveillance cameras, door locks, and bulletproof glass. But these methods aren’t backed by research and may not prevent a shooting or reduce the number of people harmed by a gunman.

Since the Columbine shooting in 1999 that sparked national media coverage of these tragic events, it’s become routine for students to sit through active shooter drills. One school in Alaska used the sound of real gunfire. Some argue that these drills save lives, while others say they unnecessarily traumatize students.

The more pressing issue, Cornell said, is gun violence across the nation, where on average 319 shootings occur every day. “A map of the shootings that occur in one week in the United States would blot out the school shootings that occurred in the past two years,” he wrote.

Restaurants see 10 times as many shootings as schools, Cornell pointed out, yet there aren’t calls to arm waitresses and chefs with guns or install bulletproof glass to protect diners.

But some argue that in the face of fear, data like these can seem meaningless to parents and students.

University of Florida professor Dorothy Espelage, who studies bullying and harassment, grapples with this conundrum. She knows the data — that school shootings are rare — but she still worries about the safety of her nieces and nephews at school.

“We can look at the science … that school shootings have been down … but no one has been listening to that,” Espelage said. “That fear is real. I think it’s totally normal for someone with children to want schools to protect them.”

That’s why Espelage, who is working with Florida school districts after the Parkland shooting in February that rocked the state, said she focuses on “softening where they’re hardening” — incorporating mental health supports as schools add more security. Espelage trains school resource officers on trauma-informed care and works with schools to make sure students have meaningful relationships with adults so that they feel connected.

In response to the Parkland shooting, Florida passed a $400 million gun law in March that raised the minimum age for owning a gun, allowed teachers to be armed, expanded the number of school resource officers, and increased mental health services.

Leaders at the Florida PTA have found that more parents are concerned for their children’s safety and have been advocating for security measures as well as mental health services in schools.

“Especially here in Florida, with what we’ve been through, parents are afraid,” said Angie Gallo, vice president of education development at the Florida PTA. “We see the headlines. We see the news. It’s in parents’ backyards, and when it’s in their backyards, it frightens them.”

But at the same time, PTA leaders recognize that school shootings aren’t the most pervasive form of violence — or even of gun violence — in their communities. National news outlets don’t give the same coverage to shootings that happen in poor neighborhoods as they do to school shootings, yet that type of violence is much more prevalent, data show.

“There’s violence every day in our communities as well that affects our children and that isn’t quite as visible,” said Linda Kearschner, president of the Florida PTA. “We have to make our entire community safer for children.”

School shootings have been on the decline since the 1990s, along with gun violence generally, though most people don’t realize this, a Pew Research analysis found.

The ’90s was also when media coverage of school shootings began to ramp up, said Ron Avi Astor, a professor at the University of Southern California who studies school behavioral health. Astor has observed this trend in other countries, too, where a pinnacle moment — such as multiple student suicides linked to bullying in Norway in the 1980s — attracted significant media coverage and spurred a national reckoning.

In this light, increased attention and fear over an issue can cause change, spurring new laws, funding, and programs, he said.

“We think media coverage is actually playing a positive role in changing the national norms, the consciousness of what’s acceptable, and what’s OK,” Astor said. “Before, all this stuff was happening at much higher rates, but people didn’t care.”

Astor acknowledged the downside — that constant headlines can cause people to think a problem is getting worse, instilling more fear. But he also pointed out that a certain level of concern is warranted over an issue as serious as children dying, regardless of whether there’s been an improvement.

He recalled when, as a researcher, he was working with a school in Detroit to help decrease the number of students who were raped. A year later, the researchers had achieved a 50 percent reduction in these assaults. While an impressive number, it was a horrifying reality to Astor that three students were sexually assaulted that year.

Similarly, some argue, the national consciousness shouldn’t rest until the number of school shootings is at zero.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)