“We know that it’s not going to be business as usual at the Department of Education once [DeVos is] appointed, so we like that,” said Robert Enlow, president and CEO of EdChoice.

Enlow, whose group advocates for free-market programs like education savings accounts and vouchers, put the odds of some sort of school-choice program advancing under GOP control of the White House and Congress at well over 50 percent.

Almost certainly, there would be Democratic opposition in the Senate. But one way for Republicans to get around that would be through a process known as budget reconciliation.

Education watchers, welcome once again to the swamp of congressional procedure.

(The 74: How Would Trump Gut Obama’s Education Policies, Anyway? The Congressional Review Act)

The budget process starts when both the House and Senate approve budget resolutions that set broad spending and revenue levels and national priorities for the coming years.

Budgets can also include instructions, called budget reconciliations, requiring committees in both houses to approve legislation that helps further the goals of an approved budget. Instructions from 2015, for example, put in motion additional bills designed to dismantle Obamacare. (President Obama vetoed the final version of that legislation.)

To expedite consideration of those measures, the budget reconciliation process prevents Senate filibusters by requiring only a simple majority vote and limiting debate to 20 hours. This would cut off procedural avenues that Democrats could use to slow or stop consideration of the bill.

There are some limits on budget reconciliation bills—they can be used only for measures that affect revenues (taxes), mandatory spending (on things like Medicare, food stamps or other entitlement programs), or the long-term national debt limit. The Senate can consider just one bill dealing with each issue per year.

In the House, Budget Committee Chairman Tom Price — whom Trump has nominated to be secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services — on Wednesday put forward some proposals to change the timeline of the process and institute some spending limits. Changes would have to be adopted in legislation next year.

Should Republicans put forth a tax-reform package, as they have pledged to do, some school-choice proposals could easily fall within those categories.

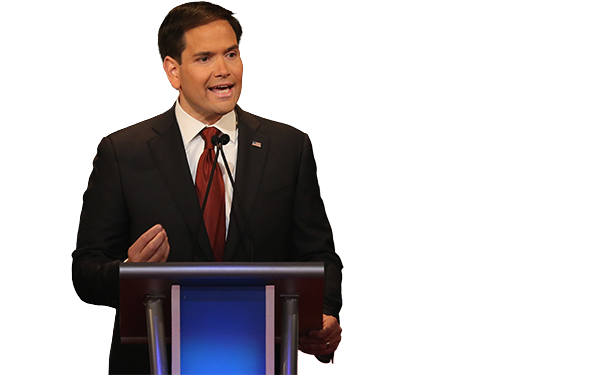

Past GOP plans that could advance through budget reconciliation include expanding 529 tax-free savings accounts from higher ed to K-12, raising the contribution limits on existing tax-free Coverdell Education Savings Accounts for K-12 expenses, and creating a tax-credit scholarship program at the federal level, similar to what exists in many states. (Former presidential hopeful Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida is the most prominent proponent of the tax-credit scholarship proposal, modeled after a program in his home state.)

However, a large-scale program like the $20 billion voucher plan Trump has proposed, which likely would reallocate discretionary spending, probably could not be advanced through budget reconciliation.

All this assumes Republicans in Washington will agree on the best approaches to expanding education options for families. But there could be a split between those committed to a federal hands-off policy and those who favor pushing school choice even if it means government intrusion into local decisions.

(The 74: Role of Unions and 3 Other Things Education Conservatives Are Eyeing in a Trump Presidency)

Enlow, for instance, favors expansion of 529 or Coverdell accounts over a new federal voucher program because, he says, a voucher expansion could require private schools receiving the funds to follow federal rules on special education or other issues.

“While we need to get families more options, we’ve got to realize it has to be state-focused and it can’t increase the regulatory environment,” he said. “The key thing here is to make sure that we don’t extend the power of the federal government into the states. That’s a real issue.”

The Dick & Betsy DeVos Family Foundation provides funding to The 74, and the site’s Editor-in-Chief, Campbell Brown, sits on the American Federation for Children’s board of directors, which was formerly chaired by Betsy DeVos. Brown played no part in the reporting or editing of this article. The American Federation for Children also sponsored The 74’s 2015 New Hampshire education summit.

The DeVos Family Foundation has also donated to EdChoice, formerly known as the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice.

The Walton Family Foundation has donated to both EdChoice and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)