40 Years After ‘A Nation At Risk,’ Key Lessons About the Future of School Reform From Newark, New Jersey

Cami Anderson: Here’s what happened when a city tried to rethink a “system of great schools” for every student.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The 74 is partnering with Stanford University’s Hoover Institution to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the ‘A Nation At Risk’ report. Hoover’s A Nation At Risk +40 research initiative spotlights insights and analysis from experts, educators and policymakers as to what evidence shows about the broader impact of 40 years of education reform and how America’s school system has (and hasn’t) changed since the groundbreaking 1983 report. Below is the project’s chapter on key lessons learned from school reform efforts in Newark, New Jersey. (See our full series)

When A Nation at Risk was published in 1983, I was twelve years old. I was growing up in Los Angeles as one of three birth children in a diverse family of fourteen, and I had witnessed firsthand the unacceptable circumstances my adopted brothers and sisters experienced in a broken child welfare system. It was clear to me that our education system was similarly broken, and I could plainly tell that succeeding in school was much easier for those of us who held privilege.

As the child of two dedicated civil servants who are avowed Democrats, I never would have guessed that a report coming out of the Reagan administration would help spur a transformative movement that would tap into my activist, social justice upbringing and provide a path for me to play a small part in moving the needle on education equity.

We’ve come a long way since 1983. Over these many years, my friends and colleagues in the school reform movement and I have led hard-fought progress—as well as committed some glaring missteps. These years of experience, coupled with a deep and growing body of research, have yielded invaluable lessons for how we, as a nation, can come ever closer to delivering on the promise of education excellence for all kids.

Educational leaders have used these decades to explore an entire continuum from tweaking and refining existing systems to innovating and disrupting the status quo. The solutions are out there. The talent is out there. Even the money is out there. So what is holding us back?

In this chapter I will share reflections from our attempt to answer this question in Newark, where I served as superintendent from 2011 to 2015. Building on the lessons and experience from nearly twenty years of reform, we launched a number of ambitious but commonsense reforms, culminating in the “One Newark” plan. Our goal was to engage the entire community and its leaders to address the educational needs of every child in every neighborhood in Newark. It was a bold and controversial effort that aimed to bring the best of what educators and policymakers had learned about driving change through top-down systems reform, bottom-up community demand, innovative labor approaches, and new school models.

Much has been written about the personalities and political drama in Newark during that time, but almost nothing has been written about the actual playbook and results. More importantly, I believe the reform efforts there still serve as useful examples to illustrate what is possible, what we should correct, and where we should go next.

Examination of this period in Newark will raise critical questions about what policymakers and community leaders at all levels should do to foster a system holistic and flexible enough that it would address the needs of all children, especially those our current systems of education and social service have historically and consistently failed the most. I will outline four steps policymakers can take to catalyze change and center the students and families who face the most challenges.

The road to reform in Newark

I was appointed superintendent of Newark Public Schools (NPS) in 2011 by then governor Chris Christie and the state’s education commissioner at the time, Chris Cerf. While most school districts have a local board charged with hiring a superintendent, NPS had lost that authority back in 1995, when the state took control of the district.

New Jersey’s constitution has uniquely strong language compelling the state to intervene in the event of chronic failure. As far back as the 1967 rebellion in Newark, there had been growing political support for the state to step in and address the city’s abysmal student achievement, despite vehement objections from local elected officials.

I was the fourth in a line of state-appointed district leaders to arrive with a mandate for reform and improvement to Newark. But my arrival came with an even greater sense of urgency. About nine months before my first day, multibillionaire Mark Zuckerberg famously announced on The Oprah Winfrey Show, seated next to Governor Christie and Cory Booker, then mayor of Newark, that he was making an unprecedented one-time gift of $100 million to the city’s school reform efforts. Just prior to this, the governor had also announced his decision not to renew my predecessor’s contract, sending a clear signal that change had not moved quickly or decisively enough in Newark.

It was clear that Newark school improvement was a signature political issue for Christie, and the pressure to raise achievement and improve efficiency was intense. On a trip to Washington, DC, earlier that year, he proclaimed to national media that “in the city of Newark, we are spending $24,000 per pupil, and public money for an absolutely disgraceful public education system—one that should embarrass our entire state.”

Indeed, as I arrived in Newark, 39 percent of students who entered the system failed to graduate, and only 40 percent of third-graders could read and write at grade level. Enrollment was plummeting. The district’s nearly forty thousand6 students and one hundred schools made it the largest in the state, with the majority of students living below the poverty level. The schools themselves were a physical manifestation of the deterioration and decay. I still shudder at the memory of rats floating in basements amid boilers dating back to the 1950s and of Lafayette Elementary School (built when Abraham Lincoln was president), which had actual mushrooms growing in the cafeteria after Hurricane Irene.

Local politicians and families had grown impatient. For the five years prior to my arrival as superintendent, many elected leaders had become early adopters of a growing national charter school movement that aimed to free individual schools and networks of schools from government red tape and allow them autonomy to innovate and build excellent schools. These supporters included Booker (then a young councilman), school board member Shavar Jeffries (who now heads the charter school behemoth KIPP Foundation), and state senator Teresa Ruiz, among other notable local leaders. Charters weren’t the only new option—other school models, such as magnet high schools (often with entrance requirements) and partner-run small high schools, had gained momentum too.

Some of these schools had notable evidence of improving achievement for Newark students, and it was understandable that they were gaining strong support from local leaders, influential funders, and certainly the families of the nearly 5,500 students who were enrolled in them. Indeed, Zuckerberg’s gift earmarked a significant amount of funds to growing the charter and small-school footprint. A plan between Christie and Booker that was leaked to the press around this time (causing uproar in the community) revealed that a central focus was to build more charter schools and open new small schools as quickly as possible.

It was clear that the most impactful efforts at improving schools in Newark were actually working around the very system they were trying to improve. And in New Jersey, these new schools were funded on a per-pupil basis; in other words, the money followed the child out of the traditional system and into the public charter system. Logically, this made sense. But in practice, this proliferation of competitors to district-run schools was creating unintended consequences that few wanted to discuss.

During the interview process to become superintendent, though, I was very eager to discuss it. What was the long-term plan to ensure that students who remained in traditional district schools benefited from the cash infusion as much as those who were lucky enough to win school enrollment lotteries? What about the school closures and layoffs that would be inevitable when the footprint of traditional schools shrank? Would charter and new-school growth help bring excitement and excellence to our poorest neighborhoods, or would it give some kids better schools but make the conditions in their communities worse? Wouldn’t the district end up serving more students who required the highest levels of support? No one seemed to have answers for these tough questions.

I had questions for the anticharter folks too. How could you blame families for exercising choice given the abysmal conditions of many traditional schools? Why were thousands of families on waiting lists? What policies—labor and otherwise—were holding traditional schools back from succeeding? Why hadn’t those policies been advanced? Were community leaders ready to push the bold reforms necessary for traditional schools to compete with charters? And what should we do about the chronically failing, profoundly underenrolled schools? The answers to these questions were complicated and generally had only to do with adult politics, not what’s best for kids.

My background and the questions I asked made a lot of people very uncomfortable. Some saw me as “antireform” because I wasn’t “charter-friendly” enough, especially with the eyes of the nation now on Newark. At the same time, others felt I was in cahoots with the “privatizers” trying to kill public education by supporting new school models. In hindsight, it is easy to see that my story was just an example of a growing and deeply polarized national debate on whether and how we can radically improve the quality of education for low-income families and students of color at scale. Meanwhile, from day one, our team wasn’t focused on winning favors or promoting specific ideologies. We were focused on great schools for all kids in every neighborhood, by any means necessary.

Building a ‘system of great schools’

Given the perilous state of the city’s schools, the unrealistic expectations around quick achievement gains, and the pressure from ideologues on all sides, many speculated that the superintendent role wasn’t doable. But I was inspired by the scale and the ferocious commitment of many leaders in the community.

I interviewed with a large committee and countless stakeholders, who spent hours debating diverse theories about what to do to improve schools. I was also moved by the unusual personal and political alliance formed by Christie, a popular Republican governor in a Democratic state, and Booker, a popular mayor and rising Democratic star, to do something bold. Something was in the air, and it felt like transformation was possible for children and families who had been failed by public systems for generations. I was convinced, perhaps naively, that if we could harness the debates and emotion around what to do, we could lift up a whole city. I remember thinking, There are one hundred schools—we can do this!

I assembled a diverse team of exemplary senior leaders—some known and trusted from within Newark, some with a track record of results elsewhere, and some with a lot of promise who were ready to step up. When I say “we” in describing the work in Newark, it is not simply rhetorical. I cannot take sole credit for anything we accomplished in those four years; it was this stunning team that acted as both the architects and the engineers behind the policies and practices we implemented, tirelessly, on behalf of Newark families. I wish I could list them all here by name.

It was time for us to craft our own plan for Newark’s schools. We started with the theory that the unit of change was the school itself and embraced the idea that what we were building was what my former boss, then New York City Schools chancellor Joel Klein, called “a system of great schools,” not a “great school system.” This was a subtle but profound distinction, because it meant we were seeking to ensure that there were one hundred excellent schools serving every child in every neighborhood—regardless of governance structure.

In the long term, we knew that Newark required a citywide master plan that would account for every school building and every child. But in the immediate term, we had obvious and dire issues to address in the district’s own schools.

First, we needed to set a unifying goal for the district: every child would be college ready. That’s right, college, not just career—because we believed that choice of higher education should be up to the student, not simply determined by the inadequacy of their preparation, and because Newark families were demanding this.

While college readiness is an obvious educational goal for affluent families and communities, in Newark it was far from obvious that this was attainable or even desirable for most students. But to families, it was obvious. In poll after poll, focus group after focus group, they told us very clearly: they wanted their children to graduate college ready. Moreover, they believed that “career ready” was a euphemism for low expectations. Families felt that academic excellence was a passport out of poverty.

Most parents were with us from day one. The challenge was the well-meaning funders and other influencers who wanted to muddy the waters and talk about everything except whether students could read, write, and do math at grade level.

To make a case for action, we shared baseline achievement data and started to create a sense of urgency around this critical goal. Looking unflinchingly at this data wasn’t easy, and it made many educators and leaders uncomfortable to acknowledge so blatantly how poorly our schools were preparing our students to succeed in life. When we started sharing actual data about proficiency rates and the number of young people earning diplomas indicative of their mastery of hard content, we started to encounter real pushback, both within and outside the school system. This was a theme I became increasingly familiar with: often what families say they want can be quite different from what those who speak for them are willing to stand for.

Ensuring ‘four-ingredient schools’

With our North Star established, we rolled up our sleeves to improve the district, school by school. By this point in US education reform, it had been nearly thirty years since the release of A Nation at Risk, and there was a large and growing body of research and evidence about high-performing schools in high-poverty neighborhoods. Combined with our team’s years of on-the-ground school transformation experience, we zeroed in on four basic ingredients that every high-quality school possessed: people, content, culture, and conditions.

To extend the cooking analogy, we knew each ingredient could have a different flavor profile in a different environment. The exact mix of ingredients varies based on context as well. Getting all four ingredients right in a school building is a huge challenge on a good day and nearly impossible the rest of the time. And yet the ingredients themselves are relatively uncontroversial—even commonsense—and should be the central focus of systems leaders and policymakers.

Our aim: ensure that every NPS school was a four-ingredient school so that we could make steady progress toward college readiness for all. Our philosophy: focus on what works regardless of ideology, which often led to “third-way” solutions—combining the best of seemingly disparate views or forging a new path to transcend old, binary thinking. Our mantra: implementation matters.

People

It’s critical to have the right people in the right seats, from the leadership team to the teachers to mental health professionals to custodial staff. No matter their role, every adult in the building must be equipped with the right mindsets and skill sets to uphold the mission and goals of the school.

Education reform birthed a broad array of nonprofits and policies focused specifically on teacher quality, notably Teach for America (TFA) and TNTP (formerly the New Teacher Project), the latter with its landmark Widget Effect report. We know intuitively the power that a great teacher has, and a growing body of research reinforced this belief, showing us that teachers are the most significant in-school factor determining a child’s level of achievement. Further, the most significant factor in getting great teachers in every classroom is the quality of the principal. Meanwhile, author Amanda Ripley showed us that in Korea, master teachers are treated like rock stars, which is hardly the case here in the United States.

Partly because of my experience working on the talent side and the emerging research about the strong correlation between school leaders and student achievement, we focused on leadership from day one in Newark. I’ve never been to a great school with a mediocre principal, and I have never been to a failing school with a terrific principal (except perhaps at the very beginning of a turnaround). Within two years, we had replaced nearly one-quarter of our principals through aggressive recruiting and selection, giving preference to Newarkers and leaders who not only knew instruction but thought of themselves as community organizers and change agents.

We took a page from New York City’s playbook, enacting a “mutual consent” policy that allowed principals to select teachers aligned to their school’s goals, as opposed to having them force-placed according to seniority. We adopted a new teacher evaluation system that required more evidence-based classroom observations and feedback, taking a page from Chancellor Michelle Rhee and her team’s work in the District of Columbia. We trained and empowered principals to hold teachers accountable when they failed to uphold expectations—and we had their back when teachers needed to be removed. We created “career ladders” for teachers to become leaders without having to leave the classroom, taking a page out of the Baltimore playbook.

As was a consistent theme with our approach in Newark, pursuing and advancing third-way ideas had us making people on all sides of the issues uncomfortable. Many states at this time were starting to use quantitative test score data in teacher evaluations, and New Jersey was eager to follow suit. However, my team and I felt that the science for such “value-added” approaches didn’t hold up when it came to determining the effectiveness of individual teachers. We took a lot of flak from hardline education reformers, who had become fixated on using test scores as a shortcut to accountability and who worried that our questioning the use of test scores in teacher evaluations would water down reform efforts more broadly since Newark was such a high-profile example. But not only did we feel that using the value-added approach in teacher evaluations would be unfair to teachers, we also knew that including such a poison pill in our new evaluation plan would create a backlash that could sabotage the entire effort.

To help noncharter schools accelerate the “people” ingredient, we negotiated what was widely considered an ambitious contract with Newark teachers. We were able to find agreement with both the local and national teachers’ unions on contentious issues such as freezing pay for teachers who were ineffective; on providing bonuses for high performers working in hard-to-staff subjects; on expediting firing for the small number of teachers caught doing egregious things; and on finding pathways for individual schools to innovate outside the four corners of the contract. We also asked the state to grant us a waiver from traditional tenure laws so that we could consider quality alongside tenure when making decisions about whom to retain as we set about the necessary downsizing.

Despite agreeing to key labor reforms after more than two hundred hours at the bargaining table, some in the Newark Teachers Union and their national affiliate, the American Federation of Teachers, vociferously advocated against them within weeks of the contract being ratified by an overwhelming majority of teachers. Both groups had a long track record of preserving some of the sacred cows of labor negotiations with teachers: seniority-based placement, infallibility of teachers with tenure (regardless of what they do), and resistance to any form of accountability—no matter how nuanced. Meanwhile, we found many of these ideas to be popular among everyday teachers, who told us the quality of the teacher in the classroom next door is a factor in whether or not they want to stay at a school. In fact, research shows teachers want access to high-quality curricula, comprehensive assessment systems, and the ability to collaborate with colleagues. As the granddaughter of a union organizer and as a strong believer in collective bargaining, I was pushing largely because I believed then — and still believe now—that teachers’ unions need to evolve to become part of the solution or they will become obsolete.

We also had to completely restructure and reimagine the central office to be in service to schools and families. This required breaking senior leaders into new teams and inviting them to clearly articulate how they would enable the four school-level ingredients. It also meant crafting clear plans with goals aligned with good management and coaching—not simply doing what had always been done. Many rose to the occasion and embraced the opportunity for clarity and coaching. Some didn’t. This was another necessary and politically fraught task. Newark Public Schools was one of the biggest employers in the city, so many staff on the central team were connected to a local politician, vendor, or influencer who had their back if their job was in jeopardy, regardless of whether or not the job was necessary or they were doing a good job.

Content

A high-quality school needs high-quality and culturally competent curricula. It also needs frameworks, protocols, and data that drive great instruction and continuous improvement. As computer programmers like to say, “Garbage in, garbage out.” This “content” ingredient is all about replacing that “garbage” content with engaging and carefully crafted content.

I started in Newark about a year after the Common Core State Standards had become a force nationally and the same month that New Jersey adopted a version of them. It was good timing, because I have long believed in fewer, clearer, more rigorous standards, as opposed to the laundry list I was handed as a young teacher in California. Common Core gave us an unambiguous and evidence-based target. It also served as a catalyst to scrutinize our curricula with a more rigorous lens.

The research here is undeniable; high-quality instructional materials are critical to ensuring that students are truly internalizing difficult content. Historically, though, we had all underinvested in this area in the early reforms after A Nation at Risk. A lot of us made the mistake of keeping a hyperfocus on teachers, which indulged an assumption that if we had a perfect person in every classroom, they could invent brilliant content from scratch. Fortunately, the introduction of common standards forced the issue and led to game-changing work by leaders like John King and his team in New York to develop what would become the EngageNY curriculum. Many education advisors and publishers have caught on, and there are far more “good enough” options out there, but there are still not enough.

We also were informed by systemic approaches to “managed instruction” like efforts in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, the Success for All initiative in Los Angeles, and Newark’s own NorthStar Academies (a charter network). These reforms, often literally telling teachers what to teach and how to teach minute to minute, yielded some impressive results. But they also predated important reforms around teacher quality. Our team aimed to blend the best of both by making “good enough” choices about curricula, creating spaces for teachers to use existing scope and sequences and lesson plans but also building the capacity of teachers to use data and knowledge of their classrooms to adjust.

High-quality instructional materials are an ingredient that is hard to get right when you are working only at the school or small network level. Scale is your friend. These decisions are better made at a system level, where content experts can dedicate the necessary time to addressing academic needs and cultural contexts, as well as coherence and alignment between the plethora of different curricula and assessments. It is also the area that, at the time in Newark, brought the most consensus. We did “teach-ins” for administrators, educators, influencers, and families who all really seemed to get and support the mandate for good, rigorous content that was consistent across the city.

As I write this, the country has been embroiled in a resurgence of culture wars around what we teach in our classrooms. It’s unfortunate, considering that this content ingredient was actually a rare point of local and national consensus not that long ago. The current political climate adds an unwelcome layer of complexity for systems leaders to battle.

Culture

We know from research that schools with intentionally curated environments characterized by high standards alongside high support produce better student outcomes. Students learn healthy habits, and the school community has well-established values and expectations. Norms and protocols prevent incidents, and when incidents happen, adults minimize shame and exclusion to keep students learning. In these schools, there is joy and choice.

From day one in Newark, we focused on the seminal research work and promising practices that had emerged, connecting how kids feel, how adults feel, and student outcomes. Years after comparing student achievement results to staff, student, and family survey responses, researchers Tony Bryk and Barbara Schneider found that the schools with high levels of trust were far more likely to get beat-the-odds results than their counterparts. Economists like Ron Ferguson and social policy experts like Christopher Jenks found a direct correlation between adult expectations, student surveys, and student outcomes. Though controversial, it is also no surprise to me that recent research has shown student surveys can predict student achievement as well as teacher evaluations. When young people say things like, “My teacher doesn’t stop until I get it” or, “My teacher believes I can understand anything,” or, “When my teacher asks me how I am doing, I believe s/he wants to know,” we know those students will do better. Jeannie Oakes’s Keeping Track showed very explicitly how adult biases and expectations can have a negative impact on student achievement.

Relatedly, an area where I have seen some of the greatest challenges for adults in establishing and preserving culture is in response to conflict and disruptive incidents. How we handle student discipline, struggle, and conflict is where adult biases show up the most. Black students are four times as likely to be suspended than their White peers, often for the same behaviors. Black students make up one-third of school-based arrests, though they are only 16 percent of the student population. Moreover, nationwide, Black boys are almost twice as likely to experience corporal punishment as their White peers, and Black girls are about three times as likely. Adults rate Black girls as “less innocent” than their White peers, with damning implications. Students with disabilities are far more likely to receive exclusionary discipline for subjective things like “disrespect” and “insubordination.” This is a problem not only from an equity and justice lens but also from a student achievement standpoint. Often students who need the most support and time on task are being excluded the most. Students can’t learn when they feel shame and helplessness. So it is no surprise to me that data shows that the relationship between the discipline gap and achievement is more than correlative—it is also causal.

The research squared with our team’s lived experience in Newark. Traditional schools like

Chancellor Avenue Elementary School and Sussex Avenue Elementary School, charter schools

like KIPP Spark Academy and North Star Academy’s Alexander Street Elementary School, and partner schools like Bard Early College got this ingredient right, and their results showed it. Adults, kids, families, and community partners rallied together around a common vision and values—and shared expectations and norms at the school reinforced them. Their results showed how critical it is to build a collective culture of high expectations and high support.

For these reasons, we hired administrators who showed skill in building culture and partnering with families. We created an entire central-office team focused on student well-being and discipline and charged them with building the capacity of schools to create environments where all kids would thrive and to respond to incidents skillfully. We reinvented the role of school resource officer and hosted weeklong restorative practice institutes that brought together student leaders, administrators, families, teachers, and police officers.

We made progress, but admittedly, the playbook on culture is harder to run for many reasons. Too often, discussions about what student culture should feel like are preachy, ideological, or theoretical—devoid of practical, research-based, promising practices. Building culture is far from a paint-by-numbers task. Cultures that are simply cheap forms of imitation, are inauthentic, or are misaligned to the needs of a particular community don’t create the conditions for achievement. Frequently, we think about individual tactics for establishing and preserving culture, such as specific expectations or restorative circles, but not about how they all fit together, and this leads to cultures that feel disjointed and incoherent. Effective cultures don’t feel the same in every school, but they do share key components. This is nuanced and hard to teach to administrators. At a systems level approaches to this ingredient often devolve into compliance lists and checklists. Further, the culture work requires us to surface and address adult biases about what kids can accomplish and what is considered “dangerous” behavior, and this can cause real discomfort and resistance.

Conditions

This ingredient is all about strong operations and infrastructure. The building is clean, well equipped, and well run. The trains run on time. You have the facilities, management structures, and funds to support learning, and you have the funding, supplies, and technology to support all of the other ingredients of a high-quality school.

While setting the right culture creates a social and emotional environment where both students and adults can thrive, it is important to simultaneously address the physical environment and the day-to-day operations. It may not be as compelling or sexy as the other ingredients, but none of the other ingredients of a strong school or system can succeed if we don’t address the conditions in which our children learn and our teachers teach. In Newark, we had a lot of work to do on this ingredient.

When I started in Newark, Malcolm X Shabazz High School had a river running through its fourth floor on rainy days. Many schools didn’t have air conditioning, in a city where average temperatures reach above a humid ninety degrees for months. Some schools weren’t even wired for internet access, and only a few had laptops to check out to students for the day.

Local leaders openly talked about a “rolling start” at the beginning of the school year, which referred to the fact that it took weeks to sort out the basics: enrollment, special education schedules and services, buses, and even books. Honestly, I had never heard of a system where instruction didn’t start on day one.

And while I’ve never bought into the idea that market forces are a panacea for improving school quality (and research suggests I’m right), you can bet my team took note when our colleagues at KIPP would make an overnight run to the hardware store for window A/C units to survive a Newark heat wave, while we were forced to navigate a maze of vendor regulations and nepotistic relationships just to open a window. Trust me, there’s an entire chapter to be written on reforming procurement and purchase ordering alone.

Some of these intolerable conditions were due to bad public policy and some were because of poor management. My team and I would say we could tell if a school was getting results by how visitors were greeted at the door (if at all) and how quickly families could get the answer to whatever they were asking. When organizations are well run, their primary constituents— in our case, students, families, and community members—are at the forefront of everyone’s mind. This service orientation is shared by noninstructional staff members, from the custodial staff to the crossing guard to the budget team. All are invested in the mission, goals, and shared values. We created school operations managers (similar to how some charter networks like KIPP have created business operations managers) to attend to the operational needs of the school. At the time, this got me in trouble with the administrators’ union (because I was seen as encroaching on district administrator roles and jobs). Even today our approach to operations is considered innovative, which just shows how little we prioritize the conditions in our schools.

Getting the conditions for achievement at every school in Newark was an expensive and backbreaking task, and progress was excruciatingly slow. Bureaucracy at every level—local, state, and federal—made our vision of goal-based budgeting, twenty-first-century facilities, nutritional food, and high-quality customer service feel nearly impossible on some days, even with exemplary people working on it. When academics and policymakers talk about disrupting systemic inequity, rethinking our entire system of education, or rising to the grave challenges initially posed by A Nation at Risk, they’d do well to spend a lot more time talking about basic operations. We need an entire movement to break the bureaucracy that is crippling school infrastructure.

The One Newark plan

While establishing a focus on college readiness and building four-ingredient schools was our primary focus right out of the gate, we knew we had to make progress on a citywide plan that addressed the schools beyond our purview. Looking at the full picture in Newark, you saw that everyone—local early childhood providers, the district, third-party school operators, private schools, individually run charters, and large charter networks—was doing their own thing, and the unintended consequences of this lack of coordination were becoming more evident and unsustainable every day.

From our earliest school visits, we could see that the poorest neighborhood schools were emptying out and becoming concentrated with the highest-need students and the lowestquality staff. Historic buildings were crumbling while new facilities were being built, sometimes down the street or downtown. Supply and demand were misaligned: for example, the number of magnet high school seats requiring a certain level of academic attainment far exceeded the number of eighth-graders prepared to meet them. The diversity and variety of school models wasn’t materializing; with all the new schools, we weren’t actually providing a lot of choice, just more flavors of “no excuses” ice cream at the elementary level and a bunch of run-of-the-mill high schools.

Meanwhile, every year, including my first, our district had to cut about $50 million. While there was certainly a lot of bloated bureaucracy to streamline, more than 80 percent of that money was wrapped up in people. Newark Public Schools employs many Newarkers in a city with double the national poverty rate.

With every set of data that we unearthed and every school that I visited, the pit in my stomach grew as I saw the magnitude of the challenges. Keeping open too many schools without enough students meant that thousands of Newark’s students were attending schools that were crumbling, not just physically but educationally. We were spending more money per pupil than almost every other district in the United States, with terrible results. And there was no denying that the rapid growth of the charter movement further complicated the problem.

Past district leaders—and many city leaders—viewed charters as “the enemy.” Families able to navigate the charter lotteries were fleeing the traditional system, and thousands more were on waiting lists. Who could blame them, given that many charters were radically outperforming traditional schools? As money followed students out of the traditional schools and into the charters, the available resources to revive these schools or attract talent were being stretched increasingly thin—and the trend was likely to continue. Charter leaders planned to grow the sector from serving 5 percent of students to serving more than 40 percent, which would mean $250 million of funds leaving the district with no quick or painless way to shrink infrastructure or union-guaranteed jobs. Seeing that dozens of district schools were dying a slow death, with some of the city’s neediest students trapped in them, I knew something had to be done—and soon.

As a city, we had to ask ourselves: “Is it even possible for every child in Newark to have access to a school that meets their needs? Even those children facing the longest odds?” Note that this is a fundamentally different question than “Can we get some kids in this community access to great schools?” That framing suggests we are not responsible for all of the children in our community, only those whom our school model can accommodate. It is also a fundamentally different question than “Can we build more great schools?” That question ignores the community context within which the school exists, and it fails to address very real and sometimes serious consequences when we focus on building some great schools and letting others fail. We were seeing that play out in Newark already.

Our team had no choice but to stare down these questions, which led us to some unconventional and controversial answers. The first thing we had to do: try to rise above political arguments rooted in ideology and self-interest about what type of school models should exist. There were about a hundred schools in Newark. We knew we would get to excellence more quickly if we had a variety of governance structures: traditional, charter, magnet, partner run, and hybrid. But we also knew we couldn’t simply let a thousand flowers bloom and allow others to die, especially when those vulnerable schools were serving our students with the highest need. We also knew that the community deserved excellence citywide.

Just as always, our team was guided by national promising practices and research. Only this time, we were limited by a dearth of examples in which systems leaders thought about the entire community. So we pored over our own data: student enrollment trends across governance models, overall city population trends, facilities assessments, and (of course) student outcomes. We fanned out and hosted more than a hundred community-based meetings with faith-based leaders, nonprofit executives, families in struggling schools, families in highperforming schools, charter advocates, charter operators, private schools, local funders, elected officials, union leaders, and early childhood providers. We began to socialize the idea that we needed one citywide plan across governance structures, as well as the harsh reality that the district’s footprint had to shrink. We wanted to find a way to preserve the best of the new-schools movement while also addressing some of the unacceptable consequences of its uncoordinated growth.

This process—over the course of about a year—led to a comprehensive plan we called One Newark. The plan was more than just a collection of policies and tactics. It was carefully architected with a clear and accessible framework to communicate honestly and transparently with an extremely broad array of stakeholders and get buy-in across the city. We knew that the best plan in the world would mean nothing if we didn’t tell a coherent story that motivated change.

The plan opened with three core values to drive our collective decision-making: equity, excellence, and efficiency:

- Excellence: We must ensure that every child in every neighborhood has access to a “four-ingredient” school as quickly as possible and that no kid is in a failing school.

- Equity: We must ensure that all students—including those who are facing the longest odds—are on the pathway to college and a twenty-first-century career.

- Efficiency: We must ensure that every possible dollar is invested in staff and priorities that make a positive difference for all students.

It was followed with seven focus areas, which we mapped onto the letters in the word “success” to send a clear signal of optimism and affirmation:

- (S)ystemwide Accountability: Envision and publish a standardized approach to tracking school and system success and progress across all schools (district, charter, and provider run).

- (U)niversal Enrollment: Launch a straightforward, user-friendly enrollment system that empowers our students and families to choose the school (charter, partner, or district) that best meets the student’s needs.

- (C)itywide Facilities and Technology Revolution: Create a bold plan to operationalize twenty-first-century learning environments for all students, ensuring no vacant buildings.

- (C)ommon Core Mastery and PARCC Readiness: Lead the nation in the number of students living below the poverty level (especially those currently struggling) who make progress toward Common Core mastery and readiness for PARCC, the standardized test aligned to those standards.

- (E)quity and Access for All Students: Increase the number of high-quality seats for all students, especially those currently in low-performing schools.

- (S)hared Vision for Excellent Schools: Cultivate demand for one hundred excellent schools and the groundswell of support for the changes necessary to get there.

- (S)ystemic Conditions for Success: Radically transform the district itself to ensure that it is a high-performing organization for years to come.

While the backbone of the overall picture and the building blocks of the plan were emerging in the spring of 2013, we didn’t feel we had enough operational capacity or community momentum to implement the plan that fall. Instead, we continued to engage, discuss, and refine the plan’s tenets with diverse stakeholders. We launched headlong into implementation in the winter of 2013–14.

We knew from the start that we needed a fair way to compare school quality across model types to meet the goals of our citywide vision of excellence for all. I’d seen firsthand how smart ways of tracking progress could drive good change in New York City under former mayor Mike Bloomberg, and we knew of years of research by the Consortium for Policy Research in Education and others about the correlation between accountability and student outcomes.

We started publishing “family-friendly” snapshots — across both district and charter schools — so that community members could see how their schools were doing in comparison to schools with similar populations. We looked at overall proficiency but also at growth, critical in a city like Newark with low rates across the board. We also compared schools with similar student populations to one another. There was no question that students at schools like Shabazz High School and South Street Elementary School were in much higher need than students at Science Park High School and Ann Street School. Success was possible, of course, but harder—and we needed a fair accountability system to make decisions and create the right incentives.

We created a simple red, yellow, and green system so that the community could see the landscape clearly. “Red schools” were low-proficiency, low-growth schools. Green were high proficiency and high growth (e.g., we didn’t want selective high schools to recruit “proficient” students and fail to grow them to “highly proficient”). Yellow schools were “on the move” (low proficiency, high growth) or “to watch” (high proficiency, low growth). The color-coding was clear and intuitive, and many in the community started talking about “no red schools.”

We placed an emphasis on transparent data about how schools were doing with students in poverty, students with disabilities, and English learners. We created standard measures — across district and charter schools—to report on student retention. Up to this point, accountability systems implemented under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 focused almost exclusively on proficiency, which unfortunately incentivized schools to enroll and retain students who were likely to be successful and to subtly counsel out (e.g., “you are not a good fit for this school”) or explicitly push out (e.g., through suspensions and expulsions) students who were harder to serve. We couldn’t afford to make the same mistake.

People from all sides fought us on this level of transparency — the unions, some charter schools (which weren’t obligated to share their data with us), and some funders who worried we were reducing children to numbers. But many families and policymakers embraced the information. There’s no perfect system, but there was no way to make a citywide plan without a decent measure of school quality.

We performed detailed enrollment analysis and defined the need for a common definition of a “minimum viable school.” From a funding standpoint, schools with fewer than five hundred students are hard to sustain with a staffing model that ensures things like appropriate class size, electives, teacher preparation times, and staff to attend to running operations. Newark had a lot of “red” schools that were also not financially viable, and many of them were in the poorest neighborhoods.

We also looked at demand data—who was applying to charters and from what neighborhoods, who was seeking new small high schools and from what neighborhoods, and which neighborhoods were growing and which were shrinking.

The picture was becoming increasingly clear: the need for a course correction was long overdue. We had traditional schools where 80 percent of families were on charter school waiting lists, but the district’s resistance to collaboration and the charters’ insistence on growing only one grade level each year meant large-scale closures and consolidations were inevitable.

The district had too many elementary schools overall, due to a population decrease, neighborhood shifts, and charter growth. We didn’t have enough early learning centers to meet the increased demand. We had too many selective high schools. Most of the new small high schools being incubated downtown were serving families from other wards, while iconic and historic high schools were emptying out. Overall, we had too many old buildings that were crumbling due to underinvestment and age, and some of them simply weren’t fixable. At one point, the district was paying more than $1 million just for scaffolding on vacant buildings that were never going to reopen. The picture was bleak. We had to make some hard decisions.

We decided to be radically transparent about our findings and the implications in a proposed ward-by-ward plan. Some charters should take over existing schools with high demand, keep families who opted in, and keep the buildings and the school name, instead of simply continuing to build new schools one grade at a time. Some elementary schools needed to convert to early learning centers. Some small high schools that were performing well needed to move into our comprehensive high schools, and some underperforming partner-run high schools needed to close. Magnets had to change their enrollment process. And some buildings had to be shut—some condemned, some repurposed, and some sold, potentially to charters.

Another anchor of the One Newark plan was ensuring that every family had equal access to choice. Both psychologically and practically, it didn’t make sense for one-third of families to get what they wanted and the rest to get what was left over. For starters, this dynamic was creating an almost civil war–like atmosphere, with charter and noncharter families pitted against each other and magnet and nonmagnet families screaming at each other in meetings. Also, one goal of establishing high-performing schools in high-poverty neighborhoods is to feed the groundswell of belief that kids can achieve. Newark’s choice system was helping create a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure in the noncharter schools.

We had to find a way for the idea of choice to lift all boats, but it wasn’t happening—and it can’t happen without good public policy and collective action. I’ve had many school choice advocates dispute this. Some ideologues will have you believe that the mere presence of competition somehow magically raises everyone’s game. It certainly didn’t happen that way in Newark, nor in the dozens of systems I have worked in since.

This is where universal enrollment came into play. Cities like New Orleans and Denver had implemented systems where families could access a common application instead of having to apply to and navigate multiple lotteries.43 We built on what they had learned (even flying in officials from both systems to participate in community panels) and took it a step further. We envisioned and implemented a system where all schools—charter and traditional—marketed themselves on the same timeline, using citywide approaches, and alongside our common accountability system. All families could access the system and apply to all schools. An algorithm gave preference to kids in the neighborhood, followed by kids in poverty, then kids with disabilities, and then everyone else at random.

It was a game changer. Now all schools were required to think about how to market themselves and own their quality, or lack thereof. By year two, more than three-quarters of the families of kindergartners and ninth-graders were using the system. At one point, we opened a family support center to help families exercise choice. We had actually planned for a soft launch, but word got out and more than a thousand families showed up on the first day, and the situation almost devolved into chaos. While our critics crowed about our operational failure—and it was indeed a failure—it also showed how much family demand there was for choice and quality. This is one of the hundreds of examples I’ve had throughout my career that defies the ridiculous stereotype that poor families don’t care about education.

The universal enrollment system may have been hardest on some members of Newark’s political elite who were used to the benefits afforded to them in an unfair, transactional system. I recall one meeting in which a prominent official—previously a supporter of mine—yelled, “You made a liar out of me! I told my cousin I could get her kid into this school!”

We had other “lift all boats” strategies. In partnership with the Newark Trust for Education, we created shared campus grants so that charter and district schools in the same building were incentivized to envision projects that helped their students and staff collaborate on schoolwide and community improvement projects. We asked charter teams to lead professional development for some of our turnaround schools on things like comprehensive approaches to instruction where many of them had more robust practices than we did. We created a collective action team of special educators across district and charter schools to help share and promote promising practices.

The plan meant a lot of changes for a lot of people. Some shuttered buildings were historic, and even though it was clear these buildings needed to have a divestment plan, community elders who remembered their heyday didn’t want to hear it, understandably. Many charter leaders and their supporters dug in their heels on their model of growing slowly and where they wanted to grow according to optimal facilities, regardless of the consequences. The idea of small schools within high schools—which had been successfully implemented in New York at scale—was new to Newark and, therefore, scary for many who had found their pet school to support. Some local and national funders who were excited about ribbon cuttings and smaller projects simply didn’t want to get involved in the far messier project of citywide progress.

Our team knew that the tenets of the plan were bold, unconventional, and controversial and that the politics were going to be tough to navigate. Choice, charters, labor reforms, and teacher excellence polled well. Laying off Newarkers and teachers and “closing” traditional schools or turning them over to highly successful charters were wildly unpopular. But to have the plan succeed citywide, you couldn’t have one without the other.

To add a deeper degree of difficulty, while the plan was emerging and leading up to the official launch, we suffered a series of seismic political blows at the worst possible moment. In September 2013, the Bridgegate scandal broke and increasingly sidelined Governor Christie. My team went from coordinating with his team and political allies in Newark (he had a lot)

on a weekly basis to going months with virtually no communication. Shortly thereafter, then senator Frank Lautenberg tragically passed away. Mayor Booker, who had also been an active and strong supporter of the plan and was working hard to build momentum around it, announced he was running for that US Senate seat. This not only effectively took him off the field from a local political standpoint, but also created a scenario where he needed the support of local officials and union leaders who opposed many parts of the plan. His announcement also spurred the need for an earlier-than-expected mayoral election where the leading candidates spent considerable time spewing hatred about charters and about me personally (although backstage and publicly, they had previously supported both). Shortly thereafter, Commissioner Cerf resigned. To use a sports analogy: the entire offensive line left the field.

The overall approach was comprehensive, and it had to be to ensure that none of our kids were trapped in failing schools, the district didn’t go bankrupt, communities weren’t living with vacant buildings, and the city was on a path to success. I described the plan to author Dale Russakoff as “three-dimensional chess” in an effort to convey why all the pieces had to happen at one time and couldn’t be phased. There were too many interdependent parts to a very complex system, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. Unfortunately, in her book about Newark, The Prize, which went on to become a bestseller, this quote fed an inaccurate portrayal of me as a top-down, cold technocrat—a narrative that was taking shape across much of the media coverage about our work in Newark. It couldn’t have been further from the truth—the emotional pieces of what needed to happen were not lost on me or the team. I lived with my husband and baby son in Newark and had conversations with neighbors in grocery stores and local watering holes on a daily basis. It all felt so heavy, but also necessary.

Results and lessons

During my tenure and the subsequent years under Cerf, our district teams improved outcomes for students in every neighborhood and every age group—from early childhood to high school.

In early childhood, we secured a $7 million Head Start grant48 (only the second district in the country to do so) to add more than one thousand early childhood seats. We brought early childhood standards to life and sounded the alarm to focus on the importance of high-quality early learning. Newark went from having fewer than half of our residents eligible for free early childhood programs (which was most families) to enrolling nearly 90 percent.

In 2015, the Center on Reinventing Public Education named Newark as the number-one district in the country for high-poverty, high-performance elementary schools that beat the odds. By 2019, more than one-third of Black students attended schools that exceeded the state average, compared with 10 percent in 2011. A study conducted by Harvard University showed across-the-board increases in reading and initially slow but then impressive gains in math. The number of good schools and schools “on the move” grew every year due to our district-run turnaround approach, charter conversion schools, and some outright closures and consolidations. Newark was among the top four cities in the country for student outcomes of Black students living in poverty.

The citywide graduation rate rose 14 points, closing the gap with the state average by 7 percentage points—with almost double the percentage of students graduating having passed the state exit exam. About 87 percent of Newark graduates returned for a second college term, far exceeding national averages given the high poverty rates.

And we saw signs that the overall community—despite the political rancor we encountered — was starting to believe in the “system of great schools.” For the first time in decades, student enrollment was increasing overall in Newark, as was the population of the city.

Our labor agreement, too, was a long-term success. More than a decade later, most of these terms still exist in the contract today, and an independent study of the agreement found that the “new evaluation system is perceived as valid, accurate, fair, and useful.” This suggests that its durability is not just due to luck and that the approach could and should be replicated elsewhere.

Similarly, universal enrollment still exists in a modified form to this day and is used by nearly 20 percent of families. I believe managed school choice was starting to play a role in dissipating the city’s deeply concentrated poverty.

Despite these significant accomplishments, we knew from day one that we would not succeed in Newark unless everyone, from the grandmother at a profoundly struggling school to the dad at a magnet school to the aunt at a charter school, believed things could be different — better for everyone, for Newarkers. We knew we had to build a completely new normal and that some of that work involved helping the entire community see that it didn’t have to accept the failed status quo. We exerted a lot of effort that, in the end, fell short of generating the kind of collective momentum we needed. The reasons are complicated but instructive.

Because we felt responsible for every child in Newark, we engaged all families, charter and district, with equal vigor. This was a good and mission-aligned approach, but it was almost impossible to execute, given the tensions (both perceived and very real) inherent in growing the charter footprint. The conundrum is perfectly exemplified by the mother who called in to ask me a question on-air during a local NPR show. She had just dropped off her kids at North Star Academy Charter School, she said, because she needed them to have access to excellence. At the same time, she was on her way to my office to picket against me on behalf of her nephew, who had lost his job as a school aide due to the smaller footprint of the district.

Our strategy all along was to be up front about failure and embrace accountability. Again, while our radical transparency seemed like a good idea on its face, it turned out that a lot of people don’t want to hear their school is failing—no matter how carefully crafted the message. Also, while some community members were grateful that someone was “finally telling the truth” (an actual quote from a community meeting I led at a failing school), others were understandably angry. Our team was on the receiving end of the grief and loss that result from telling the patient they have stage IV cancer when someone should have caught it years ago.

We were lucky to have a popular Republican governor in Christie and a Democratic mayor in Booker, who teamed up to create a real mandate for change and put a laser focus on what’s best for students. This was a tremendous asset (and seems unthinkable in today’s environment) but also a challenge. Some Newarkers resented the involvement of the state (particularly in managing the school system directly) and, by extension, me. And local officials fought even harder to exert influence, sometimes over off-the-mark things, to show they were relevant.

We prioritized students who were at the back of the line. Our universal enrollment system gave preference to students from the poorest neighborhoods and those with disabilities. We revamped the magnet school admissions process to look at multiple factors for student admissions at the central office. These were good decisions for children, families, and equity, but it also put us in the crosshairs of power brokers who were used to getting what they wanted and considered coveted seats theirs to give out. They also had access to the biggest microphones and would use them to mobilize the community against our efforts.

Some charter school operators and their supporters mobilized their constituents in opposition to these citywide efforts as well. They wanted to grow where they wanted to grow, not necessarily in alignment with supply-and-demand patterns or the overall plan. Many (not all) were content to crow about how much better they were than the district without digging into what percentage of “high-need” students they were serving—conveniently avoiding an apples-to-apples comparison that was much more complicated. They enjoyed promises from politicians and funders that were out of alignment with the One Newark collective plan. Many liked running their own lotteries because they had more control over admissions; some would say things like “we don’t offer that kind of special education program.” Also, many had legitimate concerns about turning over enrollment processes to a district that had been underperforming and had actively sought to extinguish them for many years.

Charters weren’t the only group stuck in their own goals and plans—and at least most of their concerns were in service of building quality schools. School-based partners and vendors, local nonprofits, funders, and other leaders all had their individual projects, schools, and pet issues. The incentives to keep doing one’s own thing were profound. I was stuck in a daily loop of explicit and often threatening demands to support individual agendas—many of them having nothing to do with what was best for individual neighborhoods and schools, let alone the collective. A local reporter continually nagged me about shoring up my “natural allies.” I remember wondering who they were. Breaking up monoplies and pursuing third-way ideas is a lonely endeavor, particularly in cities like Newark, with its transactional, machine politics.

Well-resourced forces of opposition spent a considerable amount of money spreading misinformation and actively attacking me personally. They made expensive sandwich boards, posters, and fliers with my face on it. In one image, the word “Liar” was printed as if it were carved into my forehead and dripping blood. It was an open secret that they hired a full-time blogger to write stories about our work and about me personally (some with twists of the truth and some with outright lies). The blog was well formatted, looked like a real newspaper, and generally contained kernels of truth that were leaked from inside. Ads were purchased to place those stories in actual newspapers so that they looked like real news. Canvassers were hired to distribute leaflets about false school closures, and social media stalkers posted where my family and I were eating dinner.

As important as we knew collective buy-in was to our success and as much time as we invested in it, our team was ultimately not successful in creating a groundswell quickly enough. We certainly had moments, but not enough. The One Newark plan should have been envisioned before the unintended consequences were at our doorstep. Maybe that would have given us more time. Surely, I was the wrong messenger: a White woman from out of town who represented the system. One Newark could have been a third-party entity with representatives from various sectors and a trusted, local leader. I thought this all along but failed to get stakeholders to agree and execute quickly enough. Meanwhile, we had to balance the budget and ensure quality in education.

I also clearly made mistakes. My messages were not straightforward and sticky enough. This work, as you can see, is complex and multifaceted, and I could have paid more attention to how to ensure good, proactive, community-friendly communication. I did not lead our team in good enough ways, small and large, to predict and combat misinformation that was rampant and that got even worse as social media exploded during my tenure. The forces for the status quo were organized and mobilized, and we were caught flat-footed. I didn’t manage the flow of information with nearly enough precision, let alone attend to building my own brand. I made a classic mistake that many leaders have made before me: I presumed that if I did good work and led with authenticity, people would support progress.

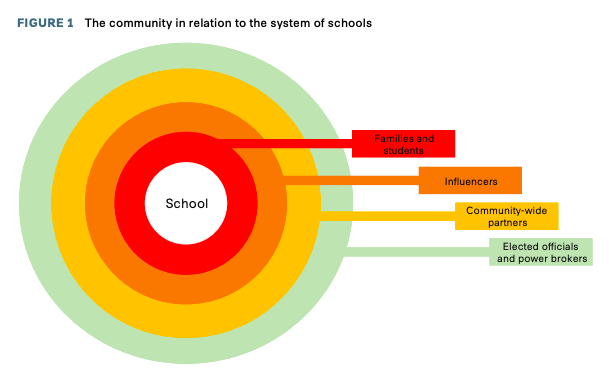

More critically, I poured valuable energy into the community without focusing as much as I should have on the community influencers closest to our work at the school level. Since then, I’ve developed a more sophisticated understanding of how to see the community in relation to the system of schools. In figure 1, the center is the school, and the next level out is the families and students (red ring). The next ring is influencers (orange ring)—folks connected to the school who have direct influence on that specific school. The next ring is community-wide partners (yellow ring)—community-based agencies and other city agencies like police and child welfare. And the next ring out (green ring) is elected officials and power brokers—for instance, pastors of large congregations, thought leaders, and community-based organizations serving the city.

We knew it was critical to focus on our families and students, and we knew it was a tremendous amount of our work to build collective action focused on them. I give us high marks for our dogged and strategic work on the red ring. But in retrospect, we spent far too much time with folks in the outermost ring—the political and power class—and not enough with those in the orange and yellow rings. It wasn’t until nearer the end of my tenure that we started to create a database for each individual school’s yellow ring. We also made a much more concerted effort to know the civil servants at all of our partner agencies. I came to realize a hard lesson—that while the politicians and power brokers confidently spoke for the community, they were often after a political win: a contract, a coveted spot in a school, a policy, or a job for a family member or friend. I wish I could take precious minutes I spent with those in the green ring and reinvest them in the yellow and orange rings.

The painful but informative experiences I had in Newark, along with a long career since then of working with systems leaders across the country, have convinced me that collective action is the missing link for change at the systems and community levels. Sadly, it is also the element I find most commonly reduced to uninspired bumper stickers and is wholly disconnected from the powerful and real work of reform. We talk about “community engagement” without honestly defining who the community is. We talk about consensus when real and hard calls have to be made every day about managing access to scarce resources, coveted high-quality seats, and community-based jobs. Many of those decisions can be in direct tension with building a system of great schools in every neighborhood by any means necessary. We interchange concepts of true grassroots organizing with community engagement and sidestep the obvious truth that power brokers and special interest groups have an organized, well-resourced, and often outsized influence on speaking for the community.

Recommendations for systems leaders

While the work we did in Newark has been treated by many in education reform as a critical case study for emerging superintendents and district leaders, it is often told as a cautionary tale of doing too much and ignoring community engagement. What is often lost are the lessons for building a successful “systems of schools.” Fundamentally, the story of the One Newark plan is a story of a district seeking to break out of the shell of its narrow school footprint and hold itself accountable for the educational futures of all its city’s children. The story of Newark should push all of us to define the role of the “system” and why it is so critical and yet so difficult to fulfill that mandate for an entire community.

Since A Nation at Risk was published, we’ve had important attempts at systemic reform that focused on specific pieces of the puzzle. Sadly, many of those efforts focused narrowly on individual “ingredients” (to use my earlier analogy) but not on the whole recipe, or the whole system.

We’ve had a lot of reforms focused on “community engagement” approaches, like the Annenberg Challenge. But those initiatives failed to address the fundamentals of building better schools and didn’t wrestle with the extremely tricky work of defining community that is illustrated in the Newark example.

We have also seen many efforts to build better individual schools; most of the charter and “high-quality schools”’ movement has been about that: creating individual proof points without thinking about the layer above the school, let alone the community. New Orleans shows the profound limitations of this strategy, as the city still struggles to figure out the role of the system after watching a bunch of individual charter operators solve some problems and create new and complicated ones. The Newark case study illuminates that while this approach can be vital for building “four-ingredient” schools, it will always be insufficient for establishing a holistic system of great schools.

We must focus on creating systems of great schools—not great school systems, not individual schools alone, not one piece of a puzzle, not some simplistic version of community engagement. We need to get clear on the roles of leaders at the systems level. In short: the system should manage the incentives, policies, guardrails, and resources to ensure that every child has access to a four-ingredient school by doing four things.

1. Enable ‘four-ingredient’ schools

As discussed above, we have promising practices when it comes to ensuring a gamechanging principal in every school and an excellent educator in every classroom. We know the impact of high-quality instructional materials that are culturally competent. We have proven research on the importance of school culture and handling discipline. We know what conditions have to be in place to enable achievement. Systems leaders should set direction and advocate; procure best-in-class materials; set policy to incentivize districts, schools, and charter management organizations to implement what we know works; and sanction practices antithetical to student progress. As one example, when Mississippi focused on the science of reading, providing best-in-class materials, training, and a way of measuring progress, kids across the state started reading at unprecedented levels. As another example, Nebraska adopted high-quality instructional materials statewide and provided options but also high-quality implementation support. This drove impressive gains in student outcomes.

Too often, cities select a superintendent or states select a commissioner because they are zealously focused on one single ingredient. Sometimes cities and states simply won’t touch an ingredient because they don’t want to fight with the union or other interest groups.

Policymakers have a responsibility to ensure that schools can obtain and mix best-in-class ingredients more quickly—trying to do so one school at a time doesn’t make sense. A lot of this work happens at the district and network levels, but leaders at all levels must put people in place who understand and are committed to all four ingredients.

2. Ensure quality and equity

Our current system of districts versus charters sadly guarantees that many kids—particularly those with the most challenges—are left behind. Policymakers and community leaders should be held accountable for allowing kids and families to fall through the cracks.

Leaders need to step up and raise their hands for being accountable for all kids to access high-quality schools. They need to embrace good enough ways of measuring what that means—in terms of what students are learning and how they are feeling. Accountability systems need to help families hold schools to a standard of excellence for all kids, including those who consistently fail in all kinds of schools. These accountability systems should be family friendly and public. And they should explicitly shine a light on where inequities show up: fewer Black students having access to AP course and magnet programs, special education students in segregated classrooms with abysmally low student outcomes, inequitable criminalization of student behavior, and kids living in concentrated poverty too often getting the lowest-quality staff. Our new accountability systems should correct for some of the mistakes we made before, from focusing only on proficiency and meaningless graduation rates to treating growth, college-readiness, and retention as critical outcome measures.

Effective accountability systems have incentives that inspire schools and communities to step up. As one recent example, schools that were designated as failing were more than twice as likely to make big gains than those that weren’t. Researchers surmised that this is because the label drove resources and supports where they needed to go—and rallied communities to do better. Good accountability systems drive decisions, sometimes hard ones, about redesigning schools, radically changing who runs them and how they are run, and even closing them.

3. Break up bureaucracy

A fundamental way to clear a runway for accelerated school improvement is to actively tear down past practices and federal, state, and local policies that block individual schools from innovating. As one example, school finance formulas are unnecessarily complicated and opaque. Most states have an even worse and more complicated approach to funding facilities and infrastructure. We need more of a “whiteboard” approach than one that tweaks decades of dysfunction.

Traditional schools will never be able to “compete” with charters if we don’t actively tear down the unnecessary bureaucracy in existing schools. As one example, when Klein was New York City Schools chancellor, he had an entire team dedicated to creating one-stop compliance and communication approaches for principals in New York City over multiple years. They shrank thousands and thousands of pages of sometimes competing “mustdos” (most of them having nothing to do with serving students better) and still felt there was more to do.

Policymakers and community leaders need to wake up every day wondering what they can do to ensure that people running schools have the time to do the right thing as opposed to managing byzantine policies and procedures from competing departments. We certainly need oversight and compliance, but it must be streamlined and reexamined every year.

4. Create cross-system and community-based solutions

The students who face the most challenges have generally been failed by multiple systems. I have a term for this: students whom systems have failed the most (SSFMs). Statistically, they are likely to be students of color. Too often they are labeled “special populations” and further marginalized out of classrooms and into separate and unequal programs. Very few schools of any governance structure meet the needs of these young people. Schools—and the systems in which they operate—are consistently failing 20 percent of their most vulnerable students.

Often these students and their families are connected to multiple systems: child welfare, public housing, homeless services, juvenile justice, criminal justice, immigration services, family services, and food programs. Some examples: nearly 90 percent of the juvenile justice population were in foster care at some point in their lives. About one-third of thirteen-toseventeen year-olds experience some sort of homelessness. These students struggle tremendously in school. In other words, we take the kids who—through no choice of their own—have been failed by one system and then fail them in another.

In order to truly reverse patterns for students that systems have failed the most, we need crossagency and community-based solutions with school success at the core. Neighborhood-based collaboratives, like the Harlem Children’s Zone, have produced promising results that we started to scale during Arne Duncan’s tenure as secretary of education. I’ve had the pleasure of working with teams creating memorandums of agreement between disparate agencies—the DA’s office, probation, public housing, and school systems—to share data and create common family support plans for young people and families connected to multiple systems. We need more out-of-the-box ideas to aggregate services and help students who are the most vulnerable succeed.

Conclusion

The insights and recommendations I’ve shared above are not based on any specific ideology. They were developed out of necessity and refined through years of application and practice across a wide variety of settings—from New York to California and many places in between, in both districts and charter networks, in small-school communities, and in the largest cities and states.