3 States Cite School Climate Surveys in Their ESSA Plans. Why Don’t Others Use Culture for Accountability?

Of the dozen state ESSA plans that have been submitted so far to the U.S. Department of Education, most have nothing but praise for school climate surveys as measurements of school quality. But when it comes to actually using surveys as accountability measures, most states back away.

Only three states — Illinois, Nevada, and New Mexico — have school climate surveys as part of their “fifth indicator,” a new accountability tool in the Every Student Succeeds Act that lets states grade schools on measures other than reading and math scores. The others are turning to measures like chronic absenteeism, suspension rates, or college and career readiness instead.

“It’s not an easy thing to put into the accountability system if you’re not already doing it statewide,” said Linda Darling-Hammond, president and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute and co-author of a recent report on the place of social and emotional learning in accountability systems. “It makes sense to me that very few states would be incorporating school climate into their accountability systems.”

Illinois is one of those exceptions. For 20 years, Chicago Public Schools has surveyed teachers and students on things like safety, the learning environment, and professional support.

Making the case

Research from the University of Chicago shows the surveys accurately capture what happens in schools. Teachers who report good relationships with families and collaboration with peers stay on the job longer. Student reports on instruction quality predict what test scores will look like. The feedback on school surveys was so great that a few years ago, Illinois decided to follow Chicago’s lead and implement school climate surveys statewide.

So when Illinois had the opportunity to include school climate surveys as an accountability measure in its Every Student Succeeds Act plan, stakeholder feedback was clear: Do it. And it’s there, on page 75: The 5Essentials survey currently given by two-thirds of the state’s schools will be used to hold schools accountable for school quality.

But for ESSA purposes, it’s participation in the surveys, not what they show, that counts.

Because people may not respond truthfully for fear of consequences to their schools, “the safest thing is to grade schools based on their participation rates,” said Elaine Allensworth, director of UChicago Consortium on School Research, who has been studying Chicago Public Schools’ climate surveys. “That’s going to be less likely to potentially corrupt the data. It encourages participation, it encourages everyone to participate, so you’re not going to get a biased sample. You can have more trust in the results.”

Still, the potential for bias may argue for keeping the surveys out of accountability altogether, she said. But Jessica Handy, government affairs director of Stand for Children Illinois — which in 2011 supported a bill making school surveys a requirement statewide — said she would support expanding the ESSA measurement from participation to results-based scoring.

“We’ve seen it’s really an amazing tool to show if schools are set up for success,” she said. “I’m really glad they’ve included it.”

Nevada is using participation in school climate surveys as well, along with chronic absenteeism, as an indicator of school quality. The Department of Education said it might reconsider using participation alone once surveys become more widespread in the state, but it also cited concerns that low ratings could send a negative message about social emotional learning.

New Mexico, however, is taking another tack. In addition to participation, the state’s ESSA plan awards five points based on the school climate grades given by students. But that’s nothing new for the state that’s in its sixth year of using school climate grades as accountability measures, which it makes public on its school report cards.

State Department of Education Policy and Program Deputy Secretary Christopher Ruszkowski said he recognizes that the measurement tools need to be watched to make sure they accurately portray schools, but using actual scores rather than just participation is important because it shows that school quality, as well as academic performance, deserves to play an important role in accountability.

“We get stuck in the false dichotomy of it all,” Ruszkowski said. “It’s either academic progress or skill building. It’s social emotional health or good assessment scores. We have to be committed to smashing those false dichotomies to saying that this is a both/and proposition, that schools are responsible for both.”

Saying no thanks

But those states are the exception. Despite the widespread popularity of climate surveys, other states said they weren’t ready to make the leap. A survey in Massachusetts, for example, found that 87 percent of respondents supported using school climate as an accountability measure while 83 percent supported using chronic absenteeism. Massachusetts chose absenteeism over culture for its ESSA plan.

New Jersey took a wait-and-see approach despite stakeholder belief in the importance of social emotional development and school culture. “As data collection improves, NJDOE is interested in continuing the dialogue about what should be included in its performance reports and school accountability systems,” the state said.

Perhaps most revealing of the complicated relationship policymakers, researchers, teachers, and parents have with school climate surveys and accountability is a note in Delaware’s ESSA plan:

“Feedback from a wide variety of stakeholders … indicates that student, teacher, and parent engagement surveys provide a comprehensive picture of school climate and should be included in the accountability system,” the plan reads. “Conversely, stakeholder feedback also voiced that surveys could be ‘gamed.’ This measure will be reported only.”

So, how do we use climate surveys?

Overall, researchers generally approve of using climate surveys for accountability as long as states maintain a vigilant watch over their rollout and impact.

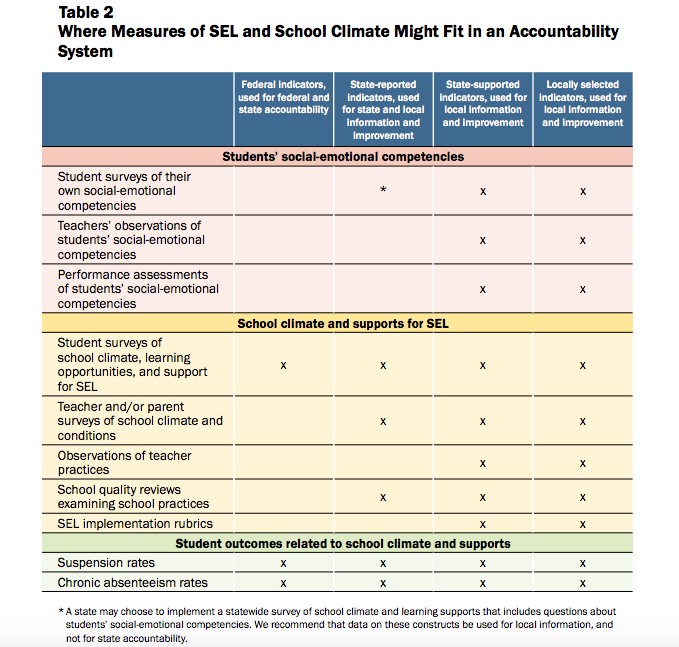

The Learning Policy Institute’s recent report acknowledged concerns about manipulation but still recommended well-researched and -tested climate surveys as a federal accountability indicator, though it argued against using other social emotional learning measures, like students reflecting on their own social and emotional competencies or teacher evaluations of their students, for high-stakes accountability.

“If a state does not yet have experience with and a culture of administering those surveys and interpreting them, it might be premature for them to say, ‘We’re going to use certain items from the survey to decide which schools go into an intervention,’ and it might prove to be problematic,” Hammond said. “I think it’s a good step-by-step approach to say, ‘Let’s see, we think it’s important to look at these data; let’s require you to do it, so to speak, and then let’s see what we learn.’ ”

Photo: Learning Policy Institute

Just because states aren’t using climate surveys as an accountability measure, that doesn’t mean they aren’t taking responsibility for both. A new brief from the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning details all the ways states can incorporate SEL into their ESSA plans, and none of these exclusively mandate using them for accountability measures. CASEL is developing an assessment work group to create practical and scientifically backed measurements for social and emotional learning.

“A lot of the work with ESSA allows states to think in broader ways about what school quality is. The specific percentage is less important than the fact that Illinois has taken a step to say, ‘Hey, this is important,’ ” said Roger Weissberg, co-founder and chief knowledge officer at CASEL. “I would like to see all 50 states say that climate is important, and we would like to give kids and teachers a voice in saying what their perception is.”

Based on stakeholder feedback that other states included in their ESSA plans, the weight given to climate surveys may continue to evolve nationwide as well.

“One of the things that’s wonderful about ESSA and the process that we’ve gone through in Illinois, having over 100 stakeholder meetings and getting 3,500 pieces of stakeholder feedback through the past 15 months, is we plan on continuing to evaluate our process,” said Illinois State Board of Education Federal Liaison Melina Wright. “While yes, right now it is a participation metric, we’re going to continue to evaluate and monitor if it’s working, and if it’s not we’ll take steps to evaluate it then.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)