3 Misconceptions About Pandemic-Related Learning Loss

Study of Illinois students shows COVID was disruptive for all children. Don't assume that only those who were instructed remotely need support

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The recent release of the 2022 NAEP scores, which showed historic learning declines in math and reading two years following the onset of the pandemic, has brought renewed urgency to conversations around learning losses and recovery. Beliefs about these topics shape how policymakers, educators and parents act to support students moving forward. Yet our research shows that common assumptions about whose learning was affected the most and what it will take for students to catch up are, in fact, misconceptions. As schools finalize their plans for spending their federal COVID relief funds, developing an accurate picture of learning declines is more important than ever.

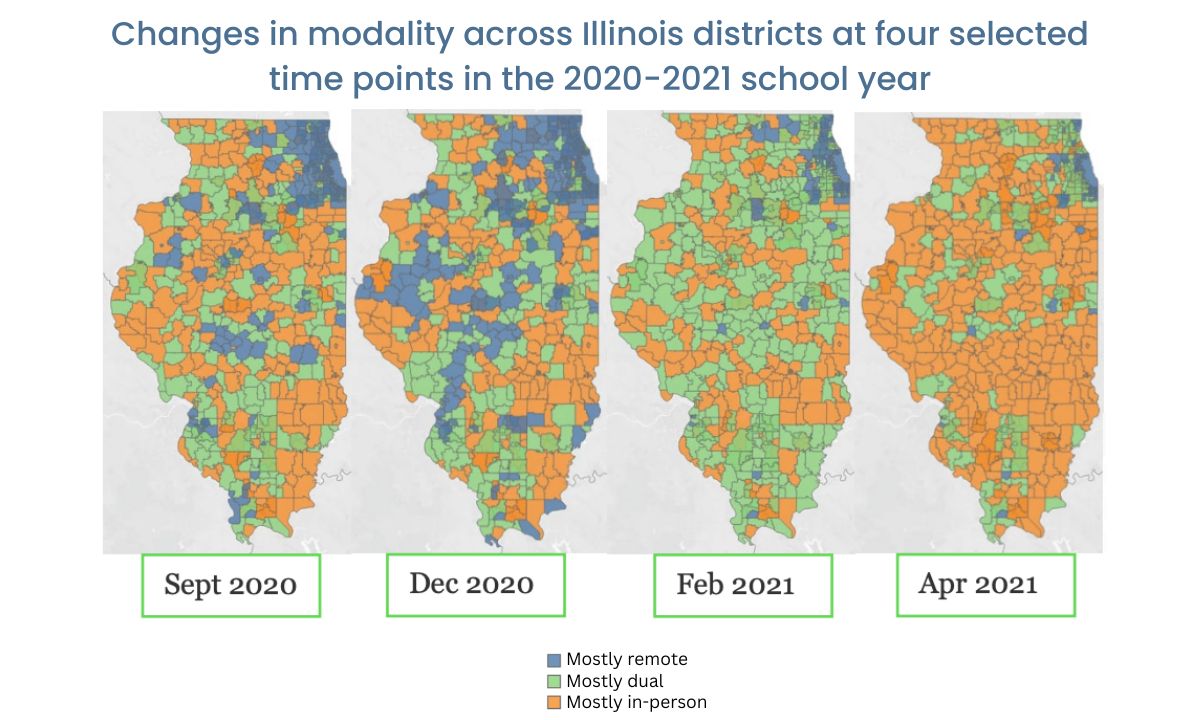

- Misconception 1: Schools were either remote or in-person. Conversations around instruction during the 2020-21 school year have tended to classify schools as either remote or in-person. However, most schools were neither entirely remote nor entirely in-person that year. In our study at the Illinois Workforce and Education Research Collaborative, we found that most schools fluctuated among modes of instruction. While some schools gradually transitioned from remote to hybrid to in-person, others transitioned back and forth as COVID-19 case rates changed, logistical challenges surfaced and parent and community demand shifted. In Illinois alone, there were 81 patterns of instructional modality changes across schools.

- Misconception 2: Only students who took classes remotely suffered learning losses.

With 20/20 hindsight about the impacts of remote instruction on achievement, it is understandable that so much of the narrative has focused on the large learning and mental health declines among students who spent the most time in virtual classes, and how schools could have responded differently (even if, given the impacts of in-person schooling on community spread of infection, many schools would likely stand behind their decision to instruct remotely). Yet keeping all schools in-person would not have prevented learning loss completely. Our research found that even students who were instructed in person throughout the entire 2020-21 school year showed significant test score declines, albeit smaller than those of students in remote learning. This was true statewide across reading and math for all grade levels, especially younger students. Other research supports this finding. Controlling for demographic characteristics, in-person instruction during most of the 2020-21 school year was associated with an 8-point decrease in math scores for grades 3 to 5. This represents about half a year of expected learning for a fifth grader. Declines among students who spent the year in person were found statewide across reading and math for all grade levels, especially younger children.

These declines among students whose schools remained open make clear that other pandemic-related factors interfered with learning. Most obvious is the experience of illness itself among students, their families and school staff. Low-income communities, whose residents were much more likely to work on the front lines as essential workers, experienced the most severe rates of COVID-19 sickness and death. These same communities saw the highest rates of job loss, food insecurity and housing instability. It is no surprise that poor and working-class children, who are disproportionately Black and brown, experienced the greatest learning declines.

- Misconception 3: Remote instruction was universally bad for learning. Despite strong evidence that remote instruction exacerbated learning declines on average, there are important exceptions. Almost all research on remote learning has looked at reading and math among students in grade 8 or younger. However, when we examined 11th graders in Illinois, we found that students in remote learning performed no worse than those instructed in person.Scores declined from 2019-2020 to 2020-21 across the board, by 10 to 17 points in math and 4 to 10 points in reading.

Even more surprising, researchers at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research showed that in Chicago, high school students’ grades were just as high in the 2020-21 school year as pre-pandemic, and a significant proportion of students even performed better, despite being instructed remotely for the majority of the year. They found that in spring 2021, 41% of high school grades were As, compared with 33% before the pandemic. The authors point out that grades have been shown to be better than test scores at predicting future academic success. Anecdotally, others have reported that some students, despite a history of struggling in school due to various learning differences, thrived in remote learning. These findings suggest that knowledge about who experienced the most remote instruction is far from a perfect guide for understanding which students need the most support for learning recovery.

With Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund aid falling well short of what learning recovery will actually cost, districts need to spend as efficiently as possible. Our research shows that the pandemic was disruptive for all children, and district leaders should not assume that students who are instructed remotely are the only ones who need targeted support. The many nuances in whose learning was affected, and by how much, means districts should allocate resources strategically, on a school-by-school and case-by-case basis, with their unique student data patterns driving decision-making.

Unfortunately, most districts have limited capacity for rigorous data analysis. Several models for data capacity support, including partnerships with local research centers and sustained data training for district staff, have begun to address this need. Unless all districts have access to effective data support systems, decision-making will be based, at least in part, on assumptions rather than reality.

Research was also contributed by Yi Wang, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research scholar at the Social Science Research Institute, Pennsylvania State University.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)