Often, though, the subsequent hiring process represents a missed opportunity for increasing the quality and diversity of the teaching staff. Several recent studies suggest that many principals, schools and districts have considerable room to improve the outcomes of this annual cycle.

In particular, some principals don’t seem to leverage available data to select the most effective teachers; many districts don’t even require applicants to teach sample lessons; districts often fail to actively recruit potential teachers of color; and teachers are frequently hired after the school year has begun, which has been shown to harm student achievement.

According to a December report from the Center for American Progress — a left-of-center think tank that backed the Obama administration’s teacher accountability policies — fewer than 20 percent of 108 districts surveyed required applicants to perform a demonstration lesson, either to students or adults. One third of those districts didn’t ensure that candidates met with a school’s hiring principal.

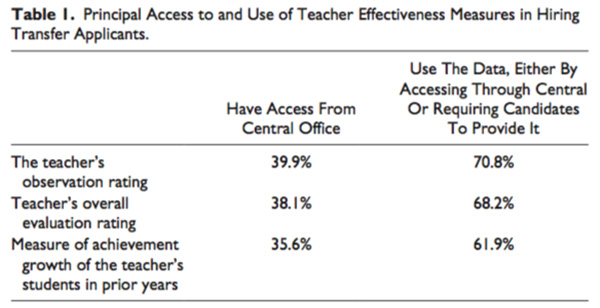

Another study, published last month in the peer-reviewed research journal Education Administration Quarterly, examined hiring practices in six large districts and two charter school networks. Use of data varied from district to district and from principal to principal. Notably, when hiring teachers within the same district, about one in three principals didn’t consider teachers’ evaluation scores. Even fewer central offices provided such data directly to principals, even though the information was likely readily available.

The researchers, who conducted extensive interviews with school principals, also found that many school leaders said they wished for information that was, in fact, available to them — though often not in a user-friendly format. “Even when principals were aware of the data available to them, they did not necessarily know how to access the data,” the study says.

Providing principals with more data, and conducting more-thorough interviews, will, of course, help only if the data and interview process are useful. Research shows this is possible.

A study of the Spokane, Wash., school district showed that its structured interview process was a decent predictor of teachers’ likelihood of remaining in the classroom and their ability to improve student test scores. Similarly, separate research done in Washington, D.C., showed that the district’s applicant rating system — based, in part, on a model lesson — was correlated with teacher effectiveness among those who were subsequently hired. A paper examining New York City teachers found that though no single trait was strongly predictive of teacher quality, a combination of measures was. Teacher-evaluation measures, though sometimes biased against teachers with lower-achieving students, have a significant degree of year-to-year reliability.

Research has shown that certification status is a strong predictor of a teacher’s likelihood of remaining in the profession. A North Carolina study found that teachers certified in-state had higher retention rates and were slightly more effective.

A key problem is not being able to ensure that principals have access to such information and, when appropriate, use it. The D.C. research showed that principals often did not make hiring decisions based on interview ratings. This may be appropriate in some cases. For instance, evidence and common sense suggest that some teachers are better matches with certain schools. However, districts should consider providing both support and accountability to make sure principals are making wise hiring decisions.

The CAP study also found that only one in three surveyed districts “actively recruit[ed] from institutions and organizations that serve primarily minority populations.” This, despite the fact that the teaching force is predominantly white, and black students in particular benefit from having black teachers.

Meanwhile, a recent Brookings Institution report finds that white education majors are hired at higher rates than those who are black or Hispanic. (This may be be due in part to lower pass rates on licensure exams among prospective teachers of color — even though such exams are less predictive of effectiveness for minority teachers.) Last year, Chicago Public Schools admitted that its screening process for teachers discriminated against black and Latino applicants.

As the Brookings paper points out, improving hiring processes would, even in the best-case scenario, make a relatively small dent in the teacher diversity gap. Still, districts should at the very least ensure that hiring processes are not discriminatory and ideally try to expand the hiring pool through targeted outreach.

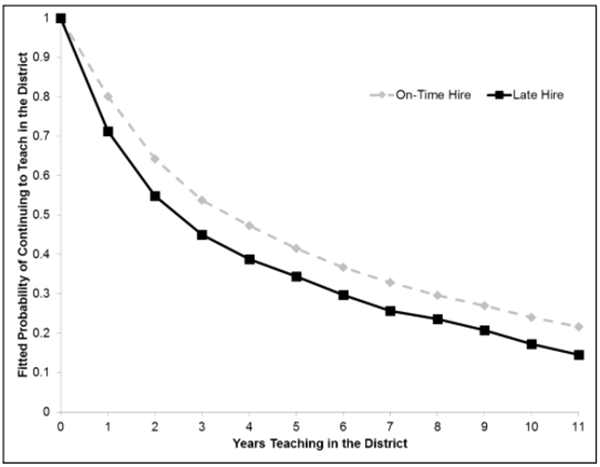

According to one recent study of a large urban school district, a remarkable 18 percent of new teachers were hired after the school year began — and the proportion was even in higher in schools with lower achievement rates and higher poverty. (Keep in mind that this is the share of newly hired teachers, not all teachers.) Predictably, those teachers were less effective, both because of the disruptive impacts of entering a class midyear and because the late-hired teachers, at least in math, were simply less skilled.

Teachers hired late were also more likely to quit teaching in the district; some studies have linked higher teacher turnover to lower student test scores.

It’s not entirely clear why so many teachers are brought on late, though the paper offers a number of explanations, including timelines for budget approvals, timing of when teachers are encouraged to make retirement decisions, and collective bargaining agreements that prioritize the hiring of certain teachers, such as those who are in an “excess pool” or looking to transfer schools. In this study, though, the district examined does not collectively bargain with teachers.

In the Education Administration Quarterly study, however, principals in some districts cited such provisions — often codified in teachers’ contracts—as a significant constraint: “Centralized rules that restrict which candidates principals can consider, or force them to hire particular teachers, were criticized for reducing principal autonomy.” In an older paper focusing on Florida, the vast majority of contracts had some restriction on the hiring of new teachers, though in many ways principals still had significant autonomy.

Another explanation for late hires is that high-poverty schools are simply less appealing to many teachers — in part, perhaps, because of poor working conditions — making it difficult to attract talent. Teachers may turn to poorer schools only as a last resort if they can’t find work in more-affluent areas. Such schools also have higher teacher attrition, on average, meaning there will usually be more vacancies to fill, which may make hiring more burdensome in a given school.

One potential way to address this problem is through signing bonuses or salary increases, which have been shown to help with teacher retention and recruitment.

All the studies cited in the piece have significant limitations. The CAP paper examined 108 “nationally representative” districts, but the survey had just a 63 percent response rate, so we don’t know to what extent the responsive districts were truly representative. The research in Education Administration Quarterly looked at just six districts and two charter school networks, based on their relatively advanced teacher-evaluation systems. The study on late teacher hiring was based on just one anonymous district.

That doesn’t mean that such research has no value — far from it — but it shows the difficulty of making broad generalizations about hiring practices in the thousands of districts and charter schools in the country.

To be clear, teacher hiring is by no means a nationwide disaster; studies show that some principals are particularly good at navigating the process and that schools in some cases are able to hire the most effective teachers available.

Insofar as hiring is a problem, the issue can’t be blamed entirely on schools, which are often constrained by resources, since a rigorous hiring process takes time and money—and most states currently allocate fewer dollars per student to education than before the Great Recession. Finally, schools face competing priorities when making hiring decisions, including many that are difficult to capture through data.

Nevertheless, the evidence that exists, particularly these recent studies, suggests that many districts and schools could be doing a significantly better job in this critical area.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)