250,000 Kids. $277 Million in Fines. It’s Been 3 Years Since Feds Ordered a Special Ed Reboot in Texas — Why Are Students Still Being Denied?

Lisa Mauldin was in the hallway at Reagan Elementary School when she saw the green box. Marked off on the floor with duct tape, the neon square enclosed a tiny desk, set apart from tables set up in small groups for the third-graders being welcomed at the back-to-school open house.

Mauldin stopped in her tracks. “Oh, hell no,” she said.

Her son’s new teacher heard her. “Is everything OK?”

“No,” Mauldin replied, “it’s really not.”

She knew without asking that the miniature desk was for Jaivyn. And she suspected it meant her son was in for another year of trouble. He had been diagnosed with multiple disabilities, and Mauldin had repeatedly asked the Leander Independent School District, which serves 40,000 students in several wealthy suburbs of Austin, Texas, to give him special education services.

Jaivyn’s pediatrician and a host of experts had diagnosed him as “twice exceptional.” This meant he was exceptionally bright — his test scores put him in the 99th percentile in reading — and struggled with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, an inability to write with his hands called dysgraphia, developmental coordination disorder and sensory processing challenges that made everything from his own clothing to classroom noises terribly jarring.

“He was just a hot mess,” recalls Mauldin. “All the hallmarks of the [autism] spectrum, except he could talk like nobody’s business.”

Despite the sheaf of documentation she had amassed since Jaivyn was in first grade, when she began asking for special education services, the school refused. When Jaivyn melted down from being overwhelmed, he was punished.

The idea behind the taped-off square, Mauldin says the teacher told her, was “to teach him boundaries, show him where he is supposed to be. If he couldn’t stay in it, he’d have to go out in the hall.”

Jaivyn ended up spending a great deal of third grade out in the hall. But Mauldin had been dealing with these issues since she adopted the boy, her biological grandson, as a toddler. She knew no amount of punishment would change behaviors that were recognized hallmarks of his disabilities.

The humiliation wrought by having to sit apart from his classmates at the little-kid desk would add chronic stomachaches to his list of struggles. “Third grade,” she says, “is when kids get to sit at tables with other kids.”

Mauldin had no way of knowing that her efforts were butting up against a little-known rule, created by the Texas Education Agency in 2004, that imposed an arbitrary, illegal cap on the number of students that schools could deem eligible for special education.

Since then, advocates estimate, some 250,000 children a year have ended up much like Jaivyn: unable to get schools or districts to acknowledge their needs, much less provide appropriate instruction. Few advocates and even fewer parents understood that an official policy, presumably imposed to cut costs, was driving those refusals. The state never announced the shift — a direct violation of the federal Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA), which requires schools to seek out any child who shows signs of needing a special ed evaluation.

While the number varies from state to state, on average 13 percent of U.S. children qualify for special education. The rate in Texas was 11.6 percent in 2004, when the state began asking districts and charter schools that identified more than 8.5 percent of their students as eligible to submit plans for reducing the number of children enrolled.

By 2015, the rate had fallen to 8.5 percent. Texas was the only state in the country to see a dramatic drop in children with disabilities served — something the agency would later insist was the result of providing such good services that students would graduate to general ed.

Families like Jaivyn’s vehemently disagree, and so do the feds. The U.S. Education Department has ordered the state to expand access to special ed — quickly and dramatically — an effort that could cost $3 billion. On paper, the cap has been abolished, the number of children being evaluated for eligibility is rising and legislators have appropriated $277 million to pay fines imposed by the department because of a separate finding that the state illegally slashed special education funding.

But the state’s elected officials who have the power to order a wholesale overhaul of the system have balked at removing hurdles that stymie parents. Law firms representing school districts in disputes like the Mauldins’ have lobbied against stronger protections for families — and their campaign contributions to lawmakers who have tabled talk of comprehensive reforms in the statehouse give them leverage unimagined by parents who have help from only a handful of advocates.

Families that do get assistance in asserting their children’s rights have half as much time to ask for due process as IDEA suggests. After hearing from lobbyists that it would “double districts’ exposure,” the state House of Representatives Public Education Committee earlier this year shut down an effort to expand the timeline from 12 to 24 months.

Even when a family navigates the gantlet and emerges with a legal finding that a school district violated their child’s rights, there’s little guarantee the student will actually get special ed services. Many, like the Mauldins, end up leaving Texas and move to other states that readily agree to provide the services their children need.

‘A perverse incentive’ to minimize students’ needs

In September 2016, a year after the duct tape incident propelled Mauldin to seek an outside advocate and then a lawyer to assert her family’s rights, the Houston Chronicle published a bombshell investigation revealing the existence of the special ed cap. A photo of Jaivyn, looking exhausted and clutching a slice of cheese pizza, ran with the story, alongside pictures of children denied help despite blindness, autism, bipolar disorder and other profound disabilities.

A number of individuals — including Mauldin — and groups had long tried to draw the U.S. Education Department’s attention to the problem. The newspaper investigation did it. After holding hearings around the state, the feds pronounced Texas afoul of civil rights law and demanded a “corrective action” plan.

Gov. Greg Abbott and top lawmakers promised a swift response, but not much has changed. Two successive legislatures — lawmakers in Texas meet for five months every other year — have nibbled around the edges of the problem but declined to take up comprehensive reform or provide schools with funding to meet the federal mandate.

In 2017, the legislature barred the TEA from instituting enrollment caps but made no other significant changes. In the 2019 session, lawmakers approved a small increase in special education funding, much of it intended to cover the $277 million fine.

The state’s defense of the funding cuts is of particular concern to disability rights advocates, who note that in July 2018, six months after the government ordered the state to overhaul its special ed programs, Texas officials went to court to argue that the cost-cutting was justified.

A panel of judges not only disagreed but lambasted the system, saying it “creates a perverse incentive for a state to escape its financial obligations merely by minimizing the special education needs of its students.”

Earlier this year, lawmakers appropriated just enough money to stave off further federal sanctions — a pittance compared with the $3 billion that the overhaul demanded by the feds will likely cost.

“I’m shocked there hasn’t been a massive federal lawsuit there,” says Melody Musgrove, Obama-era director of the department’s Office of Special Education Programs, which monitors how states serve kids with disabilities. “The fact that Texas continued to underfund special education certainly makes me question whether they are sincere about wanting to resolve this or are sincere about wanting to provide quality services to children who need them.”

When the legislature next convenes, in 2021, five years will have passed since the Chronicle report was published. Countless children who were born after the cap was instituted have aged out of the system without ever having received even the most bare bones of accommodations their schools are legally bound to provide. Right now, an estimated quarter-million Texas children with disabilities are awaiting even basic support from their schools.

Catherine Michael, a partner in the law firm that represented the Mauldins, says stories like theirs are common in Texas. “Where we’re talking about a cost to a school of maybe $2,500 to $5,000 [for services], school districts in Texas will spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to basically appeal these cases so that not only are attorneys not willing to take them, it chills other parents who would like for these services to be provided to their child.

“The goal becomes, how do we run the family out of money, or make the appeal process so long and arduous that parents just give up and leave the system.”

‘In Texas, even blind kids can’t always get services’

When Congress wrote the 1975 Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act, it required schools to seek out and evaluate any child, from birth to age 21, known or suspected to have a disability. Known as Child Find, that provision was designed to make sure districts fulfilled the spirit of the landmark civil rights law by making them responsible for any child within their geographic borders, whether attending public school or private school or in an institution.

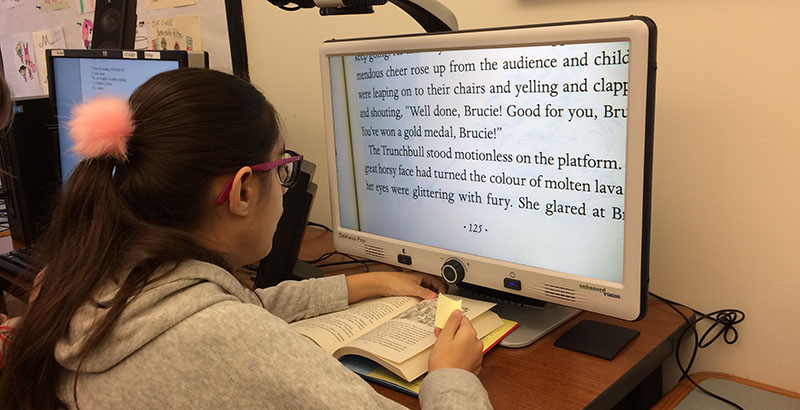

Sophia Salehi was born in 2007, weighing 9 ounces. She spent the first seven months of her life in a hospital, legally blind and suffering from lung problems. Right away, the Houston Independent School District declared her eligible for special education and began providing early intervention services. Her name was placed on the Texas Education Agency’s registry of children with visual impairments.

Sophia’s parents, Nick Salehi and Heather Beliveaux, enrolled her in a Houston ISD preschool for children with disabilities. Concerned about another student’s violent outbursts and about Sophia becoming ill and requiring hospitalization as a result of conditions at the preschool, her parents moved her to the first of several private schools. Houston ISD promised the family Sophia would get special education services in her new schools, but it never happened, according to a lawsuit filed by the Salehis in May 2018.

In July 2015, Sophia’s parents took her to the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts, which recommended they contact the state-sponsored Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired in Austin for several “critical” assessments. Among other continuing safety issues, Sophia was falling and injuring herself in school.

The family paid for a private neuropsychological report and requested special ed services from Houston ISD; the nearby school district they had since moved to, Pearland ISD; a regional office of the Texas Education Agency; and the state school for the blind. But in June 2016, Houston, which had previously provided her with services, denied the request, insisting that Sophia’s vision could improve.

For the next year, the family pressed for services but got contradictory answers from different agencies. The school for the blind evaluated Sophia and told Houston ISD she should be determined eligible, court records show. The district performed another evaluation but again found the girl ineligible.

“Even if you manage to win your hearing, are you ultimately going to get any justice? Probably no. You’re probably going to move.”

A year to the day from their first formal rejection, the Salehis filed a demand with the state for a due process hearing. The hearing officer sided with Houston ISD, ruling, among other things, that the family had missed the deadline imposed by Texas’ 12-month statute of limitations.

In May 2018, the family sued, asking a federal court to order the two districts to reimburse them for 10 years of tuition and evaluation costs. Their complaint notes that the denials kept coming even though Sophia’s story was included in the Chronicle’s series under the headline, “In Texas, even blind kids can’t always get services.”

Photos of Sophia and a description of her trying and failing to find a classroom door accompanied the newspaper investigation, yet none of the bureaucracies involved agreed to reverse course. Last year, the family moved to Massachusetts and enrolled Sophia in the Perkins school.

The Salehis’ story isn’t an outlier, says their attorney, Sonja Kerr. “We are seeing families more commonly, they just move,” she says. “There’s a real culture being permeated here that even if you manage to get one of the few attorneys, even if you manage to win your hearing, are you ultimately going to get any justice? Probably no. You’re probably going to move.”

A quiet, arbitrary enrollment cap

In 2013, advocates at Disability Rights Texas, a Houston nonprofit that receives federal funds to act as the state’s lead IDEA watchdog, noticed that despite their swollen roster of cases, the number of special education students in Texas was falling. Education Director Dustin Rynders discovered that the Texas Education Agency had created a performance target for schools, threatening increased scrutiny and potential sanctions for those that identified and served more than 8.5 percent of their students in special ed.

Those targets, implemented nine years before, were in response to recommendations by a panel, appointed by the state House Public Education Committee, to look at special education laws nationwide and suggest ways to save on administrative costs to free up funds for student services.

The state did not announce the new policy. By 2015, perhaps not surprisingly, Texas’s special ed enrollment had fallen to meet that 8.5 percent benchmark — representing 500,000 children. An estimated 250,000 more were going without. Families would later report being told their children were not impaired enough to qualify for services, were too smart, would have to spend time on a waiting list — or nothing at all.

Disability Rights Texas complained both to the TEA — then under the leadership of former education commissioner Michael Williams — and the federal Education Department. The complaints, The New York Times later noted, were ignored.

The feds certainly knew that the number of students receiving services was falling, though. IDEA contains a “maintenance of effort” provision that says states can’t shift special education costs or duck their obligations. Unless they can prove they met all needs and had money left over — something that has never happened, given that Congress and the states have short-shrifted special education funding since IDEA’s passage 45 years ago — a state can’t reduce its budget.

In its fiscal year 2012 application for IDEA funds, the agency said it had cut special education spending because fewer students needed services and their needs were less intensive. The feds imposed a fine but did not question how Texas, alone among the states, had plummeting numbers of students with disabilities. Just as they were ignorant of the cap, the advocates would not learn of the dispute or the likely fines for years, until the state petitioned a court to reverse it.

After more than two years of trying to draw attention to the cap, Disability Rights Texas turned to the Chronicle, which published its investigation three years ago. Hundreds of families, including the Mauldins, showed up to comment at U.S. Ed Department hearings throughout the state.

In January 2018, the department announced that Texas had violated the law and ordered the state to draw up a five-year “corrective action” plan. Abbott, the governor, immediately blamed school districts, which he accused of “dereliction of duty.” The districts fired back, accusing the legislature of creating the cost-cutting blueprint.

“Federal officials have provided no definitive timeline for action by [the] Texas Education Agency, but parents and students across our state cannot continue waiting for change,” the governor wrote in a letter to state Education Commissioner Mike Morath. “I am directing you to take immediate steps to prepare an initial corrective action plan draft within the next seven days.”

Given the size of the task, a week was the blink of an eye. Specifically, the U.S. Education Department asked the TEA to address two areas: its obligation under federal civil rights laws to seek out and evaluate any child suspected of needing disability supports, and its responsibility to monitor compliance in the state’s 1,200 school districts.

In October 2018, three months before the agency’s self-imposed deadline for putting revamped programming in place, Matthew Montano was appointed deputy commissioner of special populations and monitoring. At the time the U.S. Education Department released its findings, he says, the state was already working on a strategic plan to overhaul special education. In addition to the accountability systems to be created under the corrective action plan, the strategic effort aims to ensure that students with disabilities receive effective support.

To meet the two sets of goals, the TEA created two systems: one to monitor district performance and one to provide the assistance schools need to improve the quality of their special ed services. This may sound like a bureaucratic distinction, but advocates have long wished for incentives for schools to provide better programming.

The initial corrective action plan offered a huge caveat: “TEA cannot legally commit additional funds outside of those that are appropriated by the Texas Legislature and the U.S. Congress,” officials warned. “This strategic plan has been designed so that it can be sustained with existing appropriations.”

Initial estimates were that it would cost some $500 million to test the quarter-million kids who had been denied evaluations or services — the TEA was able to immediately provide $20 million to districts to get started — a likely injection of $3 billion to pay for their instruction and several years to complete the task, given how withered special education programs were statewide after 14 years of dramatic cuts.

Sped Strategic Plan April 23 Final 1 (Text)

IDEA requires states and districts to reach back to families that are denied services or provided with inadequate ones and attempt to make up for lost time. The TEA proposed spending just $30 million to do this.

School funding has been a political third rail in Texas for a generation, with angry voters demanding to know how both class sizes and property taxes could be skyrocketing at the same time. By the legislature’s 2017 session, which began six months after the Chronicle published its investigation, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle were calling for top-to-bottom school finance reform — though not an overhaul of special ed.

Legislators filed 51 special-education-related bills, 16 of them direct responses to the newspaper’s findings. “This is a major priority this session,” Public Education Committee Chair Dan Huberty, a Houston-area Republican, told the reporter responsible for the Chronicle stories. “These are our most vulnerable population of children, and we need to do everything in our power to make sure they get the resources to be successful in the classroom.”

Virtually all, however, died ideological deaths. Abbott and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, both Republicans, balked at considering a new finance system until Republican House Speaker Joe Straus agreed to advance a bill curtailing transgender bathroom rights. The state Senate would not sign on to any reform until the House agreed to create private school vouchers or tuition savings accounts for children with disabilities.

Neither Abbott nor Huberty responded to requests for comment.

Not even a special session could break the deadlock, and lawmakers gaveled the session to a close having outlawed limits on special ed enrollment, but not much more. A measure sponsored by Huberty to increase funding for dyslexia services failed, as did a bill to create a program to help students with disabilities who had been passed over make up instruction they missed.

The omissions would prove costly not just to students with disabilities but to Texas taxpayers as well. Starting a few days after the session ended, fiscal year 2018 was the third year (the others being 2012 and 2017) in which Texas told the federal government that it reduced spending on students with disabilities.

The TEA had previously sued over the feds’ decision to fine the state $33 million for the 2012 funding reduction. In November 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit sided with the U.S. Education Department.

“Though Texas law requires the state to allocate funding based on the needs of disabled children, it is the state itself that assessed what those needs are,” the Court of Appeals ruled. The model “creates a perverse incentive for a state to escape its financial obligations merely by minimizing the special education needs of its students.”

Because the decision meant the state’s funding system was afoul of federal law, TEA officials informed legislators that Texas would owe additional penalties for fiscal years 2017 and 2018 and would need a boost in spending to stave off another fine in 2019. Not including new funding to bring spending back to the legal minimum, the state would owe the U.S. Education Department $277 million.

‘Parents have to be the enforcers’

Disability advocates interpreted the justices’ opinion as a shot fired over the state’s bow: In addition to eliminating the enrollment cap and bringing special ed funding back up to previous levels, Texas would need to overhaul its system for paying for services for children with disabilities.

Instead of implementing a Marshall Plan, however, one of the state’s first moves was to ink a contract with a private company to mine students’ special education plans, or individualized education programs (IEPs), for data in hopes of identifying patterns. Disability Rights Texas and other advocates immediately flagged privacy concerns in giving student data to a commercial venture and the lack of checks and balances on the no-bid contract. Amid a swirl of controversy, state officials terminated the arrangement.

It was the first of a series of delays. In fall 2018, the feds told the state its overhaul plan did not go far enough. A January 2019 deadline to complete the steps the TEA had committed to came and went. In March of this year, the agency said it could not ensure students were being evaluated and served, or that districts were being monitored for compliance, until June 2020.

In the agency’s defense, Montano points to the scope of the task. In the 2017-18 school year, 100,000 children were evaluated for services statewide. In 2018-19, the number jumped to 138,000. Some 450 districts took advantage of state funds to help pay for more evaluations — many of them rural districts that faced distinct challenges because of their size and location.

Twenty regional offices provide assistance on strategies that deliver better outcomes for special ed students, he adds. And the state has begun training teachers statewide, both in special education and in general classrooms.

“The intent of the strategic plan is to close gaps between students with disabilities and their peers.” says Montano. “For us to make up this much ground in this amount of time, I think it’s nothing short of remarkable.”

Musgrove, the U.S. Ed Department’s former special ed chief, agrees that monitoring for compliance with the law isn’t enough. Just as Texas has attempted to address student outcomes as well, she says her former office needs more tools to address situations like this.

The main lever for sanctioning states that don’t follow the law, she notes, is to withhold funds. “Yet they’re taking money away that provides services for children who need them, so at the same time it seems like a sort of perverse outcome,” says Musgrove, now the co-director of the Graduate Center for the Study of Early Learning at the University of Mississippi. “Again, I think we’re seeing a test of the limits of federal authority in special education.”

States aren’t always as quick to act when the U.S. Education Department orders a change as the general public might think, she continues: “Texas is big. It just seems to me that they take the position that ‘We’re so big and you can’t do anything to us.’”

“Right now,” she adds, “parents have to be the enforcers of IDEA. If they don’t file a complaint, then a child might get really, really lousy services. There is no accountability that catches that before a parent has to file a complaint.”

“My child is missing out on what he needs while adults are scrambling back and forth. I would be a hypocrite if I’m evaluating other people’s kids and saying you can trust the system. I tried the system and it failed me.”

In 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a little-noticed but hugely consequential decision, Endrew vs. Douglas County School District, in which it held that students with disabilities are entitled to more than minimal special education services. Schools have a duty to enable them to make appropriate progress, academic or otherwise.

Dyslexic herself, Angela Smith is both a special education teacher and a masters-level educational diagnostician, a specialty that exists in Texas but not many other places. She taught in the Dallas Independent School District for five years before becoming a special ed evaluator for the school system. Disillusioned with the roadblocks in the evaluation process, she left that job in 2015 to teach homebound students in the district.

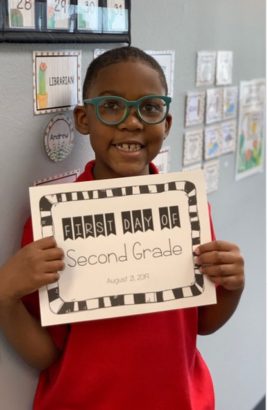

Smith has three children, and she knew the odds were good that one of them would also have learning disabilities. Her son Trent had been in first grade for a few weeks when she asked Dallas ISD for a special ed evaluation for the boy. It was November 2018, 11 months after the feds had ordered Texas to lift the cap and fulfill its Child Find obligations.

Before she asked for the evaluation, Smith had had her son assessed both by a local hospital that specializes in educational diagnoses and by an occupational therapist recommended by his pediatrician. Based on their input and her experience, she told the school her concerns were dyslexia, problems with fine motor skills, perhaps a learning disability and speech delays.

In February, the evaluator called and asked whether Smith had considered autism. The woman based her opinion on watching the boy on the school playground with his siblings.

It was the first time an autism diagnosis had been suggested, Smith says. She wasn’t scared of the label or opposed to it, but she was unwilling to change course and set aside the lengthy private evaluations she’d had done that suggested Trent had other needs.

“I finally said I wanted us to continue with the evaluation we’d started,” Smith recalls. “I was OK monitoring for autism and coming back to the table, if need be, but that right now there was no basis to substitute a diagnosis of autism.”

The next day, the district sent a letter saying that since Smith wouldn’t agree to an autism assessment, no evaluation would be done. She complained to the TEA, which told the district to go ahead with the evaluation Smith had asked for. Evaluators were free to note their suspicion there was autism in the mix, they said, but Smith’s decision did not give them grounds to close the case.

Dallas ISD turned the tables. Instead of complying with the state’s findings, the district requested a due process hearing against Smith. “What they want the hearing officer to do is to take away my parental rights and allow them to test for autism without my consent,” she says. “Honestly, it’s a power struggle.

“It took me a long time to comprehend that they were filing a due process against me,” Smith says. “I mean, if you disagree with the TEA, file against them.”

Smith expects the hearing officer to make a decision in the next two months. Dallas ISD declined to comment.

In the meantime, Smith put her son in a private school that caters to students with learning disorders. “My child is missing out on what he needs while adults are scrambling back and forth,” she says. “I would be a hypocrite if I’m evaluating other people’s kids and saying you can trust the system. I tried the system and it failed me.”

“Of course, as an employee, it makes me feel horrible. I went to Dallas ISD [as a student], so it’s kind of like my family has turned on me.

“I honestly feel like education is my calling from God,” she adds. “Most parents, their hands are tied. They don’t know their rights. [The district] knows that we have parents who are not able to navigate the system.”

‘Making sure there is a safety net for all’

House Bill 1093’s moment in the sun, when it came, lasted a hair more than an hour. Exactly 64 minutes after testimony opened in March, Dan Huberty, the House Public Education Committee chair — wearing a Rose-of-Texas yellow suit no Northern lawmaker could get away with — rapped his gavel lightly and declared the measure “left pending.”

One of a handful of special-education-related bills introduced in the 2019 legislative session, the legislation would have given families 24 months to request a due process hearing, the window the federal government suggests, rather than 12. One after another, the parents who showed up to testify described the difference the extra year would have made for their children. Often, they said, time ran out before they realized they needed the outside intervention.

But witnesses for the big players in Texas’s education landscape — including the association representing most of the state’s 1,200 school districts — urged lawmakers to table the bill. There was no need to extend the deadline, lobbyists for the powerful Texas Association of School Administrators insisted, because districts already do everything in their power to support children with disabilities.

While it places limits on the timing of some contributions, Texas allows lobbyists to donate directly to candidates’ campaigns. The law firm where Jessica Witte, the attorney who testified for the administrators’ group, works has made donations to Huberty totaling $14,000 since he was elected in 2010.

In the 2018 election cycle alone, Huberty received almost $35,000 from lawyers and lobbyists, as well as $5,000 from organizations advocating for education issues, $26,500 from public-sector unions and $7,500 from public agencies, including educational institutions. By contrast, the disability advocacy groups represented at the hearing reported no political contributions at all.

Several of the attorneys who spoke at the hearing have law practices that represent school districts in special education disputes. “By doubling the window, you are doubling school districts’ exposure, doubling their costs of litigation,” testified Holly Wardell, an Austin attorney who represents districts. “It’s a very lucrative business.”

David Hodgins, another attorney representing Texas districts, argued that the state should not have a longer timeline because of its size. “Texas is one of the largest states,” he said. “Smaller states have longer windows.”

One of the bill’s authors, El Paso Democrat Joe Moody, asked Hodgins to explain what state geography had to do with the issue. Without clarifying, Hodgins replied that Kentucky’s three-year window was a good example. A longer window would actually work against kids, he said, suggesting that disputes were more properly settled at annual IEP meetings.

At this, Moody’s co-author, fellow El Paso Democrat Rep. Mary Gonzalez, lost patience. “Kentucky!” she exploded. “Can we do better than Kentucky?”

Her little sister, she continued, has Down syndrome. Her stepfather doesn’t speak English. Between his inability to participate in school meetings and the lack of bilingual disability advocates in her community, it took the family more than a year to realize how badly the district was responding to their requests for help.

“I’ve never heard of a district that doesn’t want to hear concerns or respond to them,” Hodgins replied.

“This is not about the people who are good actors,” Gonzalez countered. “This is about the moment when there is a break … in part for us to remedy things and do we learn our lessons and it doesn’t happen again.

“The law and the policy is making sure there is a safety net for all, particularly those who are most vulnerable.”

To disability advocates, the fact that HB 1093 got even a pro forma hearing was both infuriating and a minor miracle. Since Texas lawmakers meet for such a short time, the House speaker typically pre-determines the agenda and demands strict compliance.

The midterm elections had served the state’s Republican leaders up a surprise backlash, and education issues — usually not a major factor in electoral politics — featured prominently. As a result, in the 2019 session lawmakers were laser-focused on fixing not special education but the state’s byzantine school funding system.

The final education funding bill did contain some tweaks to special ed financing. To ward off more federal sanctions for failing to maintain spending levels, it included an increase of about $900 per special ed student being served in a general education classroom.

A separate budget bill included $50 million to fund district special ed evaluations — one-tenth the estimated cost. Lawmakers also called for a task force to study the special ed funding system the federal appeals court had warned did not comply with federal law. The panel is to report back next summer.

As they prepared to table the bill, foreclosing the possibility of reform for at least two more years, lawmakers assured the school district lobbyists that they’d been heard.

“The current system in Texas,” pronounced Rep. Trent Ashby, a Republican who previously served as president of the board of the Lufkin Independent School District. “While it’s not perfect, it’s not broken, obviously.”

When due process doesn’t deliver justice

The neon green duct tape corral was just the first of Jaivyn Mauldin’s torments in third grade. As the school year unfolded, says his mother, Jaivyn was punished more than he was accommodated. If he forgot his lunchbox, he was made to run laps. Sometimes he’d be forced to write, “because they knew he hated it,” she says. He developed chronic stomachaches and begged to be homeschooled.

Near the end of the year, Mauldin placed another formal request for special education services. It took several months, but this time the district agreed with Jaivyn’s diagnoses and scheduled a meeting to draw up the boy’s IEP for Jan. 25, 2016.

By that point, Mauldin had been comparing notes with other parents who warned her not to sign the document on the spot because things discussed at meetings had a way of not showing up in written agreements. At the end of the cordial session, Mauldin asked to take the draft plan home to show to her husband. Another meeting was scheduled 10 days out, “if needed.”

On Feb. 3, she emailed the district, accepting some parts of the plan but rejecting others as insufficient. In response, she got a call from someone at the school pushing the next meeting back to Feb. 23. When she arrived, Mauldin was told the district had re-evaluated its position and no longer deemed Jaivyn eligible for special education.

According to findings, first from a state hearing officer and later from federal courts, before the second meeting, the district held a gathering of administrators referred to as a “staffing,” which Mauldin was not told about. An outside attorney from a law firm that represents school districts in special education disputes was present at that meeting and at the Feb. 23 meeting where Jaivyn’s eligibility for services was withdrawn.

After the first IEP meeting, Jaivyn had been given a computer to use to accommodate his writing deficits. His teacher had even let him pick out a case for it, Mauldin recalls: bright pink, his favorite color. At the second meeting, staff took the computer back. He was, the lawyer said, too bright to need it.

“It was so bizarre,” Mauldin recalls. “It was like they were talking about a totally different child.”

“I was scared he was going to crash and burn. I took him out and put him in a private school.”

Mauldin demanded a due process hearing. The state hearing officer who presided ended up creating a chart to track Leander ISD’s contradictory statements about Jaivyn’s needs. It covers three pages of the decision he issued in August 2016 ordering Reagan Elementary to place the boy in special education and provide extra services to make up for the lost time.

“There is a shocking difference between the opinions provided by the teachers and other district staff in … the January [IEP] meeting as compared to the statements and conclusions made during the February [IEP] and then at hearing,” he wrote.

The reversal, he suggested, was unlikely to have come from any new understanding of the child’s issues. “Rather, it is more likely that the change in statements came from ‘education’ provided by district staff during the district-only staff meeting.”

A few days after the hearing officer issued his findings, Leander ISD held another IEP meeting. It reinstated Jaivyn’s eligibility for services but refused to discuss the services the Mauldins had requested be added before the due process hearing. Fifth grade, says Mauldin, brought numerous meetings with the school and with the family’s attorney, including another due process hearing.

The district declined to comment for this story.

The family sued suit to make the district pay their legal fees — something the law entitles them to. The family won at every level, but it didn’t help Jaivyn, who was coming home sick two or three times a week and begging to be homeschooled.

“I was scared he was going to crash and burn,” says his mother. “I took him out and put him in a private school and filed for reimbursement for tuition.”

A year later, the Mauldins sold the house down the street from Reagan Elementary and moved to Springfield, Oregon. Without any hesitation on the part of his new school, Jaivyn was placed in special education. Now just starting eighth grade, he is taking honors and high-school-level courses in some subjects, and catching up in others.

His goal: go to law school and become a special education lawyer.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)