Oregon Considers $120 Million Proposal to Boost Student Literacy

The Early Literacy Success Initiative would pay for reading tutors, teacher training and require a shift to teaching methods

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A $120 million initiative to boost literacy would be one of the single largest investments of its type in Oregon history if it passes.

But during a public hearing for the proposal at the House Committee on Education on Monday, critics said it doesn’t go far enough and risks wasting money without stricter spending rules.

At the end of the hearing, the committee unanimously approved the initiative, moving it to the budget-writing Joint Ways & Means Committee. It would be the seventh major initiative attempting to raise reading proficiency for Oregon youth by the state or federal government since the late 1990s.

The Early Literacy Success Initiative, House Bill 3198, is sponsored by Gov. Tina Kotek and a bipartisan group of lawmakers, including Democratic Reps. Jason Kropf of Bend and Ricki Ruiz of Gresham, and Republican Reps. Bobby Levy of Echo and Mark Owens of Crane.

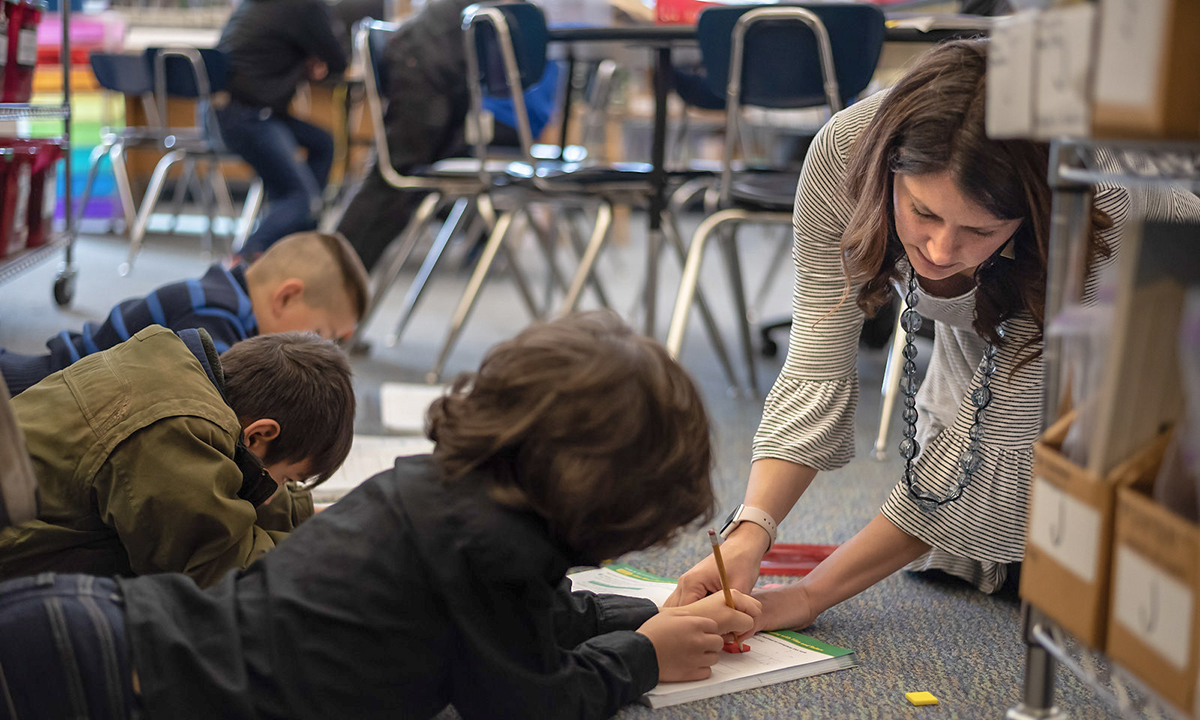

The bill would create three new grant programs to help school districts pay for K-3 reading tutors, teacher training in reading instruction, new reading curricula and summer reading programs.

It would make Oregon part of a nationwide movement promoting the “science of reading.” The movement promotes reading instruction methods rooted in phonics to change persistently low student reading proficiency.

Since 1998, just over a third of Oregon fourth graders have shown proficiency in reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress test, the nation’s report card. Yet decades of research shows more than 90% of kids can learn to read if they are taught with methods rooted in research about how the brain learns to decode written language. This research is based on decades of evidence that shows most people need to be taught the 44 sounds in the English language and how to map those sounds to letters and letter combinations to decode words. In essence, that means learning to “sound it out” and to recognize sound and letter patterns in words.

Yet literacy teaching in Oregon and in many other states has been largely based on the belief that reading comes naturally to the human brain and that children can learn to read if they’re surrounded by good books and given techniques beyond sounding out words, including guessing or using pictures.

Under the proposal, districts would need to comply with a rule that all materials, curricula and instruction be rooted in the “science of reading” to receive grant funding. The Oregon Department of Education and the State Board of Education would be responsible for determining whether districts were in compliance.

Wide support

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)