Global Learning Loss: Top 4 Takeaways from Latest International COVID Research

Analysis of studies from 15 countries finds students lost over one-third of a school year’s worth of learning, on average, due to the pandemic

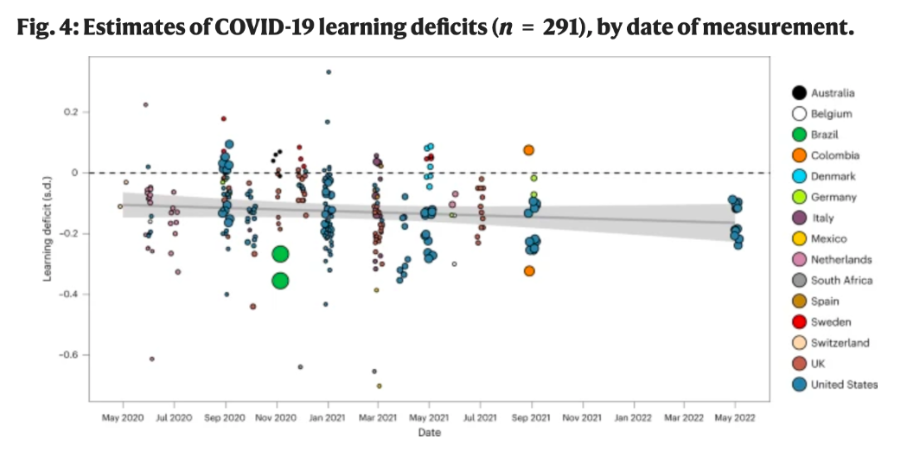

A new review of COVID-era research shows that K–12 students around the world suffered harrowing learning loss due to school closures that persists today. The meta-analysis, published Monday in the science journal Nature Human Behavior, finds that students experienced average learning deficits equal to about one-third of a school year. And the harm was more severe in relatively poorer countries and among poorer populations of students.

Those conclusions represent the latest and widest-ranging evidence yet of the damage inflicted by the emergence of COVID — both in terms of direct interruptions to schooling and the social and economic turmoil in other spheres of life. They dovetail with the observations of education experts who have also pointed to steep declines in nationwide academic performance, along with the billion-dollar investments made by governments to help schools bounce back.

But they also come as voices in the national media have argued that learning losses may be less harmful than advertised, warning in some cases that a single-minded focus on the pandemic’s toll could hurt teacher morale. With American students now returned to a post-COVID reality in the classroom, a recent speech by Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona largely skirted the subject of learning loss.

By contrast, the review, based on 42 research studies from 15 countries, calls for heightened urgency from both leaders and educators in re-setting the trajectory for student outcomes.

“The persistence of learning deficits two and a half years into the pandemic highlights the need for well-designed, well-resourced and decisive policy initiatives to recover learning deficits,” the authors write. “Policymakers, schools, and families will need to identify and realize opportunities to complement and expand on regular school-based learning.”

Robin Lake, director of the Center for Reinventing Public Education, said the findings were consistent with those of her own organization’s distillation of the existing research, released last summer.

“There is no question that learning gaps have become chasms and that while some students are catching up quickly, too many are not,” Lake wrote in an email. “This is a global concern and requires innovative and urgent action. I am deeply concerned that national educational and civic leaders in the U.S. are not taking this learning crisis seriously enough.”

Here are four key takeaways from the study:

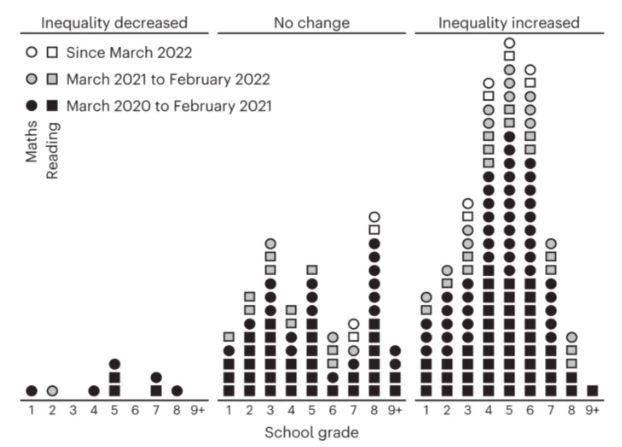

1. Inequality in education grew

While the dozens of studies classified socioeconomic status according to different metrics (including parental income, free lunch eligibility, and neighborhood disadvantage, among others), most estimates indicated that achievement gaps between richer and poorer students tended to increase in both math and reading. Most showed widening inequality during the first year of the pandemic, but a sizable number also pointed to the same trend even into its second and third years.

In an email, Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research, called the results “depressingly consistent about the pandemic exacerbating learning loss along preexisting lines of inequality.”

2. Poorer countries were hit harder too

No low-income countries were included in the analysis, as little evidence exists to identify the academic impact of COVID in the developing world. But the four middle-income countries under study (Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and South Africa) saw larger average learning deficits than their higher-income counterparts, including the three largest overall estimates of learning loss.

The authors write that the effects of the last three years are likely to worsen the long-term inequality in international learning outcomes and “undo past progress” in closing gaps across borders.

3. Learning loss is stuck in 2020

After first emerging in the early months of the pandemic, the literature suggests that learning deficits have roughly held steady in the time since. That implies that efforts to adjust to ever-changing disruptions in schools were successful in holding off further losses, the authors write, but also that those efforts “have been unable to reverse them” so far. The pattern, which appears throughout all 15 countries, is also consistent within the three (the United States, United Kingdom, and Netherlands) that have cumulatively generated the most research findings.

4. Losses were greater in math than reading

In keeping with one of the most consistent findings in education research, the review shows that academic reversals in math have been significantly greater than those in literacy. Given the greater ability of parents to teach their children reading skills, math has been characterized as a more “school-dependent subject,” and previous data on COVID-era achievement — including results from America’s foremost standardized K–12 exam, the National Assessment of Educational Progress — has already shown math scores absorbing a greater blow over the past few years. Across the study’s included in the review, reading losses at the median were only about half the magnitude of math losses.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)