Report: L.A. County’s Failure to Educate Incarcerated Youth is ‘Systemic

Decades of education and civil rights violations are due to “manufactured confusion to avoid accountability” in L.A. County’s juvenile facilities.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Local government agencies in charge of youth violated the educational and civil rights of students in Los Angeles County’s juvenile justice facilities for decades by punting responsibility and inaction, according to a report released Wednesday.

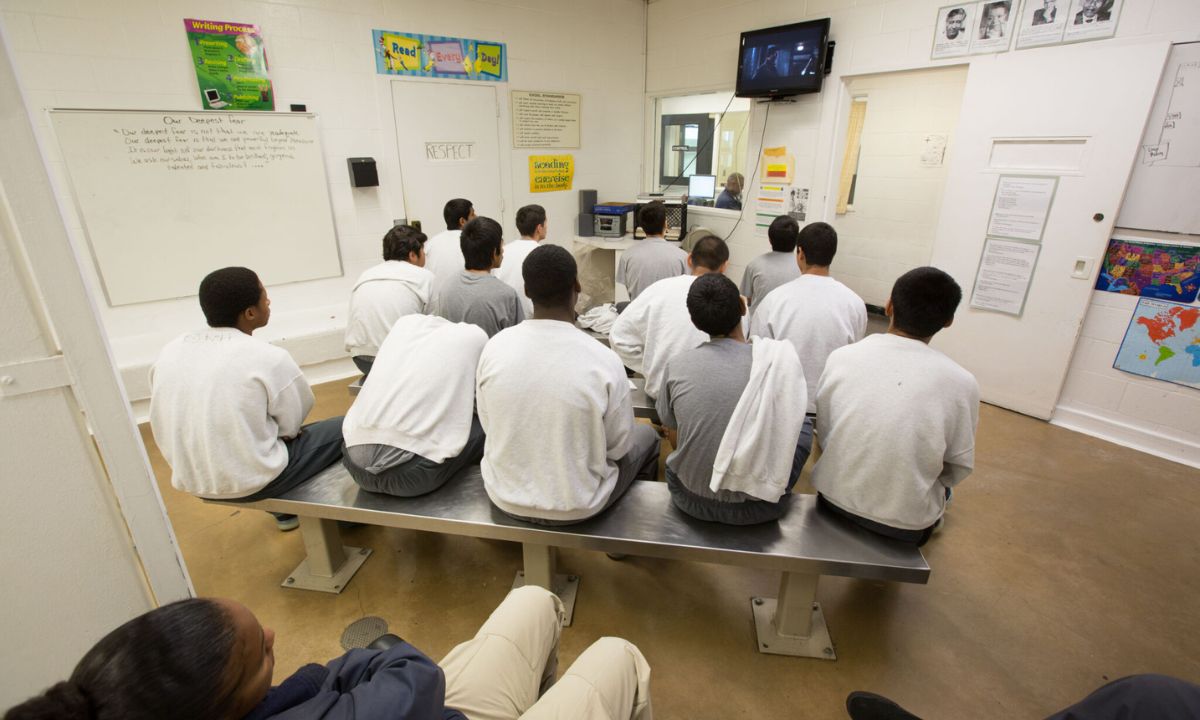

“Who has the power? Chronicling Los Angeles County’s systemic failures to educate incarcerated youth” blames the disconnected, vast network of local and state agencies — from the board of supervisors to the local probation department to the county office of education and more — that play one role or another in managing the county’s juvenile legal system, for the disruption in the care and education of youth in one of the nation’s largest systems.

“This broken system perpetuates a harmful cycle of ‘finger-pointing,’ often between Probation and Los Angeles County Office of Education, which hinders the resolution of issues that significantly affect the education of incarcerated youth,” wrote the Education Justice Coalition, authors of the report.

The coalition includes representatives from Children’s Defense Fund-California, ACLU of Southern California, Arts for Healing and Justice Network, Disability Rights California, Youth Justice Education Clinic at Loyola Law School, and Public Counsel.

The authors listed three demands for the board of supervisors, including reducing youth incarceration by way of implementing the previously approved Youth Justice Reimagined plan, providing access to high-quality education, and adopting transparency and accountability measures.

Decades of documented rights violations

A timeline outlines repeated student rights violations, some of which have resulted in class-action lawsuits and settlements requiring the county to be monitored by the federal and state departments of justice for years at a time.

Since 2000, the timeline notes that Los Angeles County has faced:

- A civil grand jury report calling on the board of supervisors to “improve collaboration” between the probation and education departments in order to address unmet educational needs

- An investigation by the federal Department of Justice — and subsequent settlements — found significant teacher shortages, lack of consistency in daily instruction, and issues with support for students with special needs

- A class action lawsuit against the county office of education and the probation department

- An investigation by the state Department of Justice, followed by settlements, found excessive use of force and inadequate services

- Multiple findings by a state agency of L.A. County juvenile facilities being “unsuitable for the confinement of minors”

Most recently, the state attorney general has requested receivership, which would mean full state ownership of the county’s juvenile halls.

The Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, the probation department, and the Office of Education did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The lasting impact of academic disruptions

Dovontray Farmer experienced the mismanaged system when he entered Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall a second time as a 10th grader. Now 24 and serving as a youth mentor with the Youth Justice Coalition, Farmer said that his time in L.A. County facilities “played a major role in not being able to get properly educated — I felt betrayed, honestly.”

Returning to school after being released was difficult, he said, because he quickly realized he was several grade levels below his classmates at his local high school.

He’d also been part of his school’s football team before his detention at Los Padrinos when he was 17, and said he tried returning to the team once released but wasn’t allowed back.

He said the disruption to his education and participation on the football team, which he saw as a positive influence, affected how he viewed his life.

“There was nothing I really could do, so I was really giving up,” he said. “Like, everything that I really cared for was already gone.”

The environment at the juvenile facilities didn’t help matters.

Los Padrinos recently came under fire after a video published by the Los Angeles Times showed probation officers standing idle as detained youths fought. Thirty officers have been indicted on criminal charges for encouraging or organizing gladiator-style fights among youths.

Farmer said he was put through those same types of fights when he was at Los Padrinos as a teenager.

“A lot of the coverage recently has been about the recent gladiator fights in 2023, but clearly this is a very systemic issue that even when a problem is resolved in the short term, we’re uncovering that it’s really indicative of a larger systemic problem,” said Vivian Wong, an education attorney and director of the Youth Justice Education Clinic at Loyola Law School, whose recent clients have included Los Padrinos students.

Education data across several years backs Farmer’s experiences while detained.

The most recent state data available when Farmer was detained at Los Padrinos is from 2018, when 39% of students were chronically absent, less than 43% graduated, and 12% were suspended at least once.

That same year, the state’s average was 9% for chronic absenteeism, 83.5% for graduation, and 3.5% for suspension.

Ongoing education concerns

The report’s authors note that students across several facilities have lost thousands of instructional minutes, with a “lack of transparency and concrete planning to ensure that the missed services are adequately made up for, leaving students at risk of falling further behind educationally.”

While compensatory education has typically been used to resolve instructional minutes owed, “I am not sure that’s the most realistic way to remedy the injustice that young people face, because they have endured so much abuse in these facilities,” said Wong. “It’s much more than just a loss of instruction.”

A more appropriate response to the loss of instructional time would be a consistent investment in avoiding detention and keeping young people in their communities to maintain school stability, she added.

Past attempts at reform have often been “done without community input or leadership, both in the design and in the implementation of those reforms,” Wong said.

The new report, she added, is meant to be a tool toward implementing Youth Justice Reimagined, or YJR, a model against punitive measures that was largely developed with input from community organizations to restructure the local juvenile legal system.

Three demands

Youth Justice Reimagined, approved by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in November 2020 to reform the local juvenile legal system, would move the county away from punitive approaches, such as detention, and toward rehabilitative support through counseling, family and vocational programming, small residential home placements, and more.

Youth detention results in “severe disconnection from and disruption to their education trajectory,” wrote the report’s authors, as they urged the board to address abysmal educational access and achievement by fully funding and implementing YJR.

The disconnect, they added, is exacerbated by delayed school enrollment when detained and upon release, the constant presence of probation officers, and turnover of educators and classmates.

These common experiences are particularly difficult for students with learning disabilities or a history of trauma, they wrote.

“After more than a decade of incremental reform, it is time for the County to truly reimagine youth justice,” wrote Supervisors Sheila Kuehl and Mark Ridley-Thomas in their November 2020 motion to approve YJR. “In the same way that the Board has embraced a care first, jail last approach to the criminal justice system, it is incumbent upon the Board to embrace a care first youth development approach to youth justice.”

Despite the approval, a report published in August 2024 by the state auditor found that less than half of the YJR recommendations had been implemented by mid-2024.

To address the high rates of chronic absenteeism, poor testing results and instructional minutes owed, the Education Justice Coalition’s second demand is to adapt educational opportunities “to address the unique and significant needs of the court school population.”

They listed 18 actions the county probation and education departments should work together on, including:

- Appropriate education support for students with disabilities

- Access to A-G approved courses for every student in a juvenile facility

- Classrooms led by educators, rather than probation officers

- Appropriately credentialed and culturally competent educators

- Education access that is not disrupted due to probation staffing issues

The coalition’s third demand centered on transparency and accountability measures by providing families with access to education planning for their children and establishing work groups that include community members.

This story was originally published on EdSource.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)