Black, Latino & Low-Income Kids Felt Better Doing Remote School During COVID

Silver, Polikoff & Hackman: Overall, students felt happier, less stressed attending classes in person during pandemic. But that's not true for all

American teens’ feelings of loneliness rose 8% and suicidal thoughts rose 5% between 2019 and 2023. Experts point to isolation during COVID-19 school closures as one key driver of this teen mental health crisis. But in a new study, we show that the reality around school closures might be a little more complicated.

We analyzed four waves of Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study survey data from the 2020-21 school year for 6,245 teens (mean age 13.2 years) nationwide. Forty-two percent of them attended school remotely, 27% attended at least partially in person, 24% moved from remote to in-person learning and 7% attended in some other pattern (moving into and out of in-person learning multiple times, for example). The racial/ethnic composition was similar to that of the United States teen population, with 53% white respondents, 14% Black, 24% Latino and 10% students with other backgrounds. The sample was approximately evenly split by gender, and about one-fourth of responding students came from households with total income under $50,000.

What did we find?

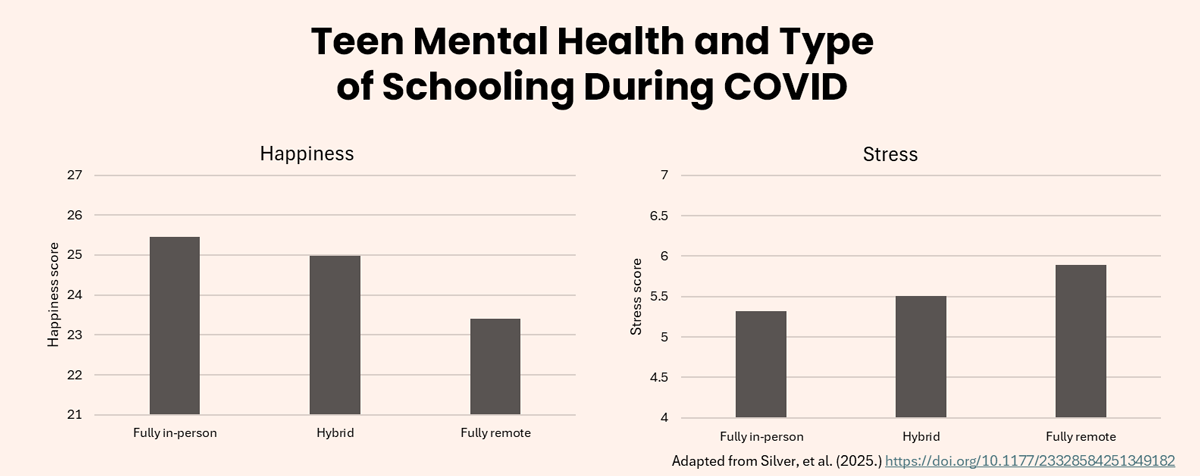

In line with the accepted wisdom, teens who attended school in person during the 2020-21 school year reported better mental health outcomes than those who took online or hybrid classes. They reported being both happier and less stressed.

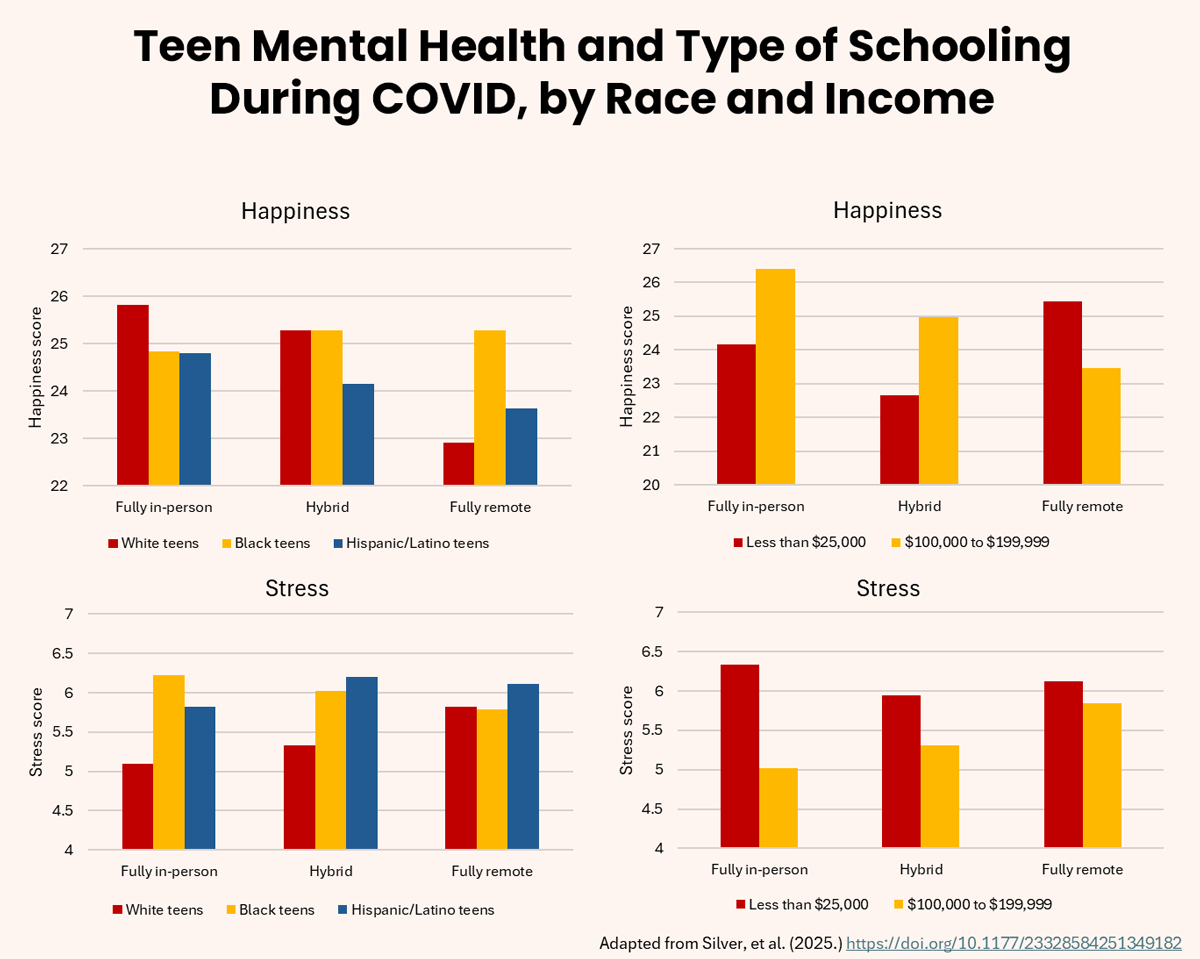

But when looking at the relationship between the type of school attended and mental health for teens of different races/ethnicities, family incomes and types of neighborhoods, we found disparate patterns.

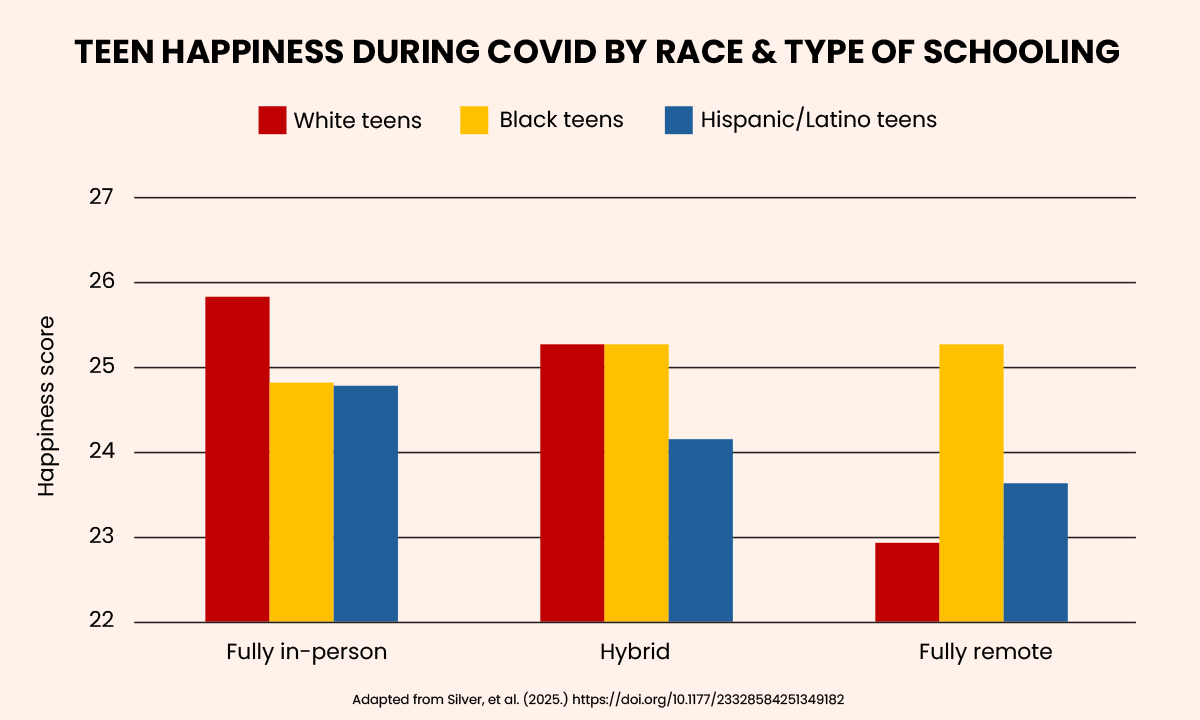

Black and Latino teens, lower-income students and those from less-advantaged neighborhoods often reported being happier and less stressed when they attended school remotely that year than hybrid or in person. This is in contrast to the finding that, overall, teens in remote schooling reported being less happy. In some cases, the less-privileged teens reported being happier than their more privileged peers in remote schooling; in others, it meant that less-privileged teens reported similar mental health across all types of schooling, whereas their wealthier classmates reported worse mental health when attending remotely.

More privileged teens were happiest and least stressed when attending school in person.

These differences were sometimes quite large. For instance, white students attending school in person scored 2.7 points higher on our 36-point measure of happiness than those in fully remote classes. But for Black students, it was the opposite — those attending in person scored 0.5 points lower. Latino students also did not see nearly the large benefit of in-person attendance as white students did. Similarly, students whose families earned between $100,000 and $199,999 a year scored 2.7 points higher when attending in person versus remote. But those whose families earned less than $25,000 per year scored 1.2 points lower. Similar patterns were seen on our measures of stress levels.

The survey responses do not contain enough information to explain these widely disparate patterns. Maybe less-privileged teens, whose families were hit harder by the pandemic than their wealthier peers, were more concerned about contracting COVID and infecting loved ones. Perhaps their schools were more stressful than those attended by more privileged teens, so remote schooling was a welcome reprieve. Whatever the reason, the type of school predicted different mental health outcomes for different groups of students, complicating the story that school closures were bad for all kids.

This is not to say that kids with different backgrounds should be encouraged to attend school remotely versus in person in the name of mental health. At a baseline, that’s segregation, which is morally repugnant. On top of that, our analysis didn’t touch on the academic harms of remote schooling, which are substantial — particularly for less-privileged students, who tend to suffer greater learning loss than their more privileged peers. When making a decision as important as whether to close schools, officials must consider multiple effects, including academics and mental and public health.

But it is critically important to get to the bottom of why students from varied backgrounds experienced different types of school so differently. If schools are to be places where all students can learn at their best and thrive, they must support the mental health and well-being of students from all backgrounds.

It is clear from our research that simplistic understandings about what happened in schools during COVID no longer suffice. Our results provide valuable new evidence that the closures were experienced differently by varied groups of students, so it shouldn’t be surprising if different student groups need different interventions and resources in recovering from the pandemic and its aftermath.

Unfortunately, the possibility of future pandemics and other disasters means spring 2020 may not be the last time U.S. schools need to close on a large scale. The next time schools shut and then reopen, less-privileged students may need help in transitioning back to in-person schooling, above and beyond the support all students will need to make up missed learning.

Research described in this article was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, Award Number R01HD108398 (PI: Hackman). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)