In Ruling’s Aftermath, Some See Beginning of the End for Department of Education

The day after the Supreme Court allowed the department to fire half its staff, Secretary Linda McMahon went ahead with plans to move key programs.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

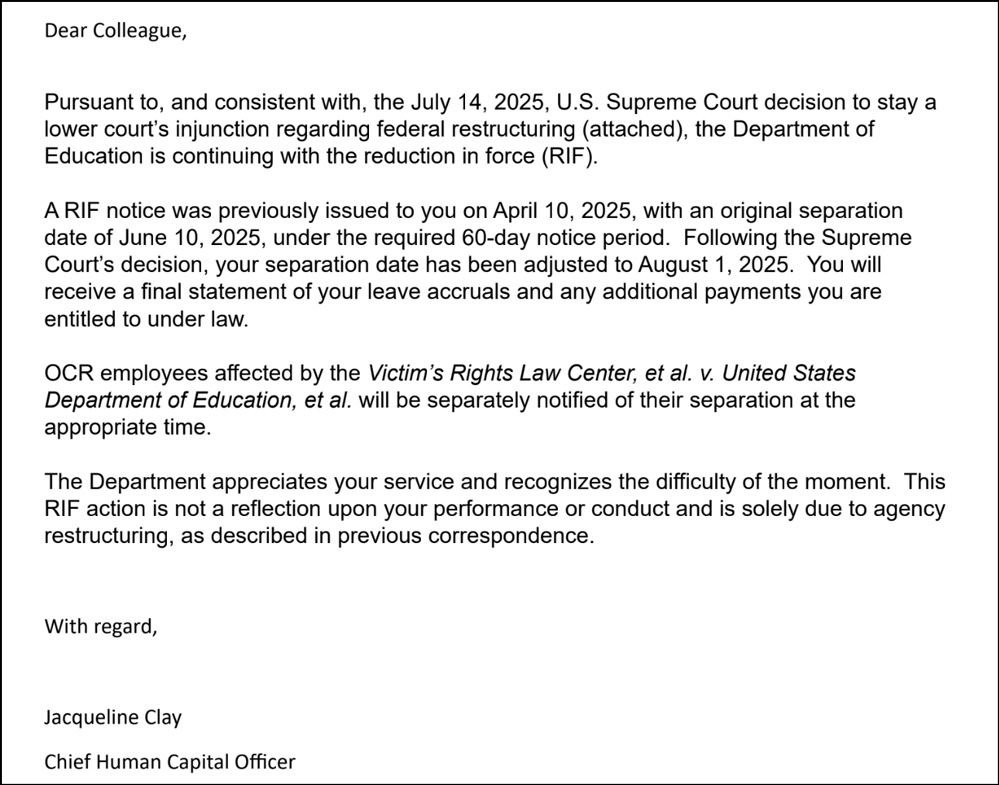

It took about 10 minutes after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling Monday afternoon for Keith McNamara and over 1,000 employees at the Department of Education to learn they were officially fired. Signed by Jacqueline Clay, chief human capital officer, the email message thanked them for their service and said Aug. 1 would be their final day.

“Came awful quick after the news dropped,” said McNamara, who worked as a data governance specialist at the department before he was dismissed during mass layoffs in March.

The department’s speed appeared to confirm just how eager the Trump administration is to hollow out an agency it says never should have been created in the first place. It was “a shame,” U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon said in a statement, that the court had to handle a lawsuit over “reforms” she said voters elected President Donald Trump to deliver. The ruling, she posted on X, brings the administration “one step closer to returning education to the states.”

But her words landed like a gut punch to employees who have been on paid leave for months, many of whom viewed the job as a personal mission to open up educational opportunities and protect students’ civil rights.

“Some people said they cried [as] soon as they saw the [ruling],” said Denise Joseph, a former management and program analyst in the Office of Postsecondary Education.

She was among the first to be placed on administrative leave in January during the initial wave of Department of Government Efficiency cuts. Now, she plans to move on with securing a new job. But her thoughts Monday were with colleagues who had hoped to be reinstated. “It’s not a good day for them, and it’s not a good day for education and our country.”

Elimination of the department is a prize conservatives have been chasing since it opened in 1979. Former President Ronald Reagan attempted to close it shortly after he took office. But the 1983 Nation at Risk report, which warned that American students were falling behind their international peers, spurred a larger federal role in education.

Speaking to reporters Tuesday, Trump said he prefers the federal government to have “a little tiny bit of supervision, but very little, almost nothing” over education. “To make sure they speak English, that’s about all we need,” he said.

Monday’s ruling overturned a lower court injunction temporarily halting the layoffs. For now, the opinion gives the administration the green light to continue downsizing the agency without congressional approval, something experts say Trump has little chance of getting.

Lawmakers in favor of closing the agency can use Monday’s ruling to “build the case that fewer people are needed and functions that are necessary could easily be transferred to other agencies,” said David Cleary, a former Republican education staffer for the Senate and now a principal with The Group, a Washington lobbying firm.

McMahon wasted no time attempting to make that point. On Tuesday morning, she announced that she would begin transitioning career and technical programs, adult education and family literacy to the Department of Labor. The press release said the move “marks a major step in shifting management of select [Education Department] programs to partner agencies.”

Transferring student aid to the Treasury Department, and special education to Health and Human Services are among the other proposals.

One former education secretary said it’s “incredibly naive” to think that Trump intends to preserve education programs if he manages to offload them to other agencies.

“The goal is not to have other agencies function. The goal is to break government,” said Arne Duncan, who served as secretary during the Obama administration. “You can’t lose the forest for the trees here, unless you’re just trying to hide from reality.”

The public isn’t sold on the idea either. A May survey from EdChoice, which supports Trump’s school choice agenda, showed that less than half of adults and parents with kids in school are in favor of closing the department.

But conservatives argue the ruling has forced “serious conversation about what the federal role should be and whether it makes sense to have a cabinet-level department,” said Jim Blew, a founder of the conservative Defense of Freedom Institute and a former department official during Trump’s first term.

The court’s decision doesn’t end the case against the department. The lawsuit challenging the firings, brought by 21 states and a coalition of districts and unions, still has to work its way through the lower courts — a process that could take many months.

“It is still technically possible for the states to prevail,” said Johnathan Smith, chief of staff and general counsel at the National Center for Youth Law.

‘Sophie’s choices’

The Supreme Court’s action effectively cuts in half a department that had just over 4,100 employees when Trump took office. The Office for Civil Rights, the Institute for Education Sciences, the National Center for Education Statistics, which runs the tests known as the Nation’s Report Card, and Federal Student Aid were programs hardest hit by the combination of firings and voluntary departures.

The secretary promises that the department is still handling its “statutory duties,” but there are signs of slippage from the gutted staff. Even before the White House Office of Management and Budget paused nearly $7 billion in federal funds that were due to states July 1, the department delayed a grant program for small, rural schools and kept states waiting on Title I funds for low-income students. Despite a court order, the department still hasn’t processed millions in COVID relief payments to states.

While OCR is now updating a website that lists resolutions to civil rights complaints, it sat dormant for several months after Trump took office. Another page with pending investigations hasn’t been updated since January. In a July 8 court filing, Rachel Oglesby, the department’s chief of staff, said of 5,164 civil rights complaints since March, OCR had dismissed 3,625 — signs, advocates say, that the department has fallen behind on its obligations to protect vulnerable students.

The court’s ruling “doesn’t augur well for the department being able to fulfil its mission,” said McNamara, the data specialist.

Others worry about states’ ability to take the driver’s seat on education, especially when the massive tax and spending package the president signed July 4 puts some of the costs for health care and nutrition programs on their shoulders.

“They’re going to be making some Sophie’s choices in terms of what gets funded and what doesn’t. Education is going to be on the chopping block,” said National Parents Union President Keri Rodrigues.

Two states, Iowa and Oklahoma, have asked the department to combine their federal funds into a block grant, an idea several other red states also support. McMahon backs the plan and often points to states like Louisiana and Mississippi, which have made strong progress in reading, to suggest that the federal government should get out the way. But Rodrigues noted that it was federally funded research and a regional education lab that helped make those improvements possible.

Maryland state Superintendent Carey Wright, who oversaw the reforms in Mississippi, didn’t just “sprinkle some literacy dust” over schools to raise proficiency rates, she said. Other red states are among those benefitting from a federal grant that pays for training, assessment and support from higher education to improve students’ performance in reading.

The parents union focuses much of its advocacy work at the state level, but Rodrigues said federal leadership is still necessary.

“I don’t know how you make progress without a department, without staff, without a Congress that’s willing to enforce federal law,” she said.

‘Serious conversation’

The court’s decision came a week after it ruled that Trump could proceed with mass firings at other federal agencies. The State Department, for example, began letting more than 1,300 people go last Friday. But that’s a far larger agency, with over 70,000 employees. The Education Department is the federal government’s smallest.

As is customary on emergency appeals, the court’s conservative majority offered no explanation for overturning the preliminary injunction issued by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by liberal Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson and Elena Kagan, wrote a 19-page dissent.

“The president must take care that the laws are faithfully executed, not set out to dismantle them,” she wrote. “That basic rule undergirds our Constitution’s separation of powers.”

Mark Schneider, a former director at the Institute for Education Sciences appointed by Trump during his first term, has long advocated for radically restructuring a federal research program that he argued had grown stodgy and resistant to change. But he wonders what McMahon can accomplish with a decimated staff.

“NCES still exists,” he said, referring to the National Center for Education Statistics. “There are three or four people in it. NCER [the National Center for Education Research] still exists. There’s one person in it. So the question is: What happens to that?”

But, he wonders, “Does the department have a plan?” Given the last few months, he said luring quality people back may prove tricky. “Even if you get any authorization to recruit, it’s going to be difficult,” he said.

A future administration could also rebuild the agency if Congress doesn’t eliminate it, but lawmakers would have to appropriate money for that, noted Neal McCluskey, director of the libertarian Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom.

To Duncan, the damage would be hard to undo.

“It’s an assault on K-12, and it’s an assault on higher education,” he said. “… Higher education has been the goose [that] laid the golden egg for decades in the United States and attracted the best and brightest around the world to come here to learn and to create jobs. We’re shutting all that down.”

The 74 Writers Amanda Geduld and Mark Keierleber contributed to this report.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)