Want Children to Cooperate? Let Them Swing Together

Researchers found that synchronized movements, such as swinging in time with each other, can promote prosocial behaviors in young children.

By K.C. Compton | July 15, 2025Cooperation is the bedrock of human society. Because the need to cooperate is so essential to human culture, it seems the simple act of performing a joint task ought to be easy and automatic. But as anyone who has coaxed preschoolers into picking up their toys or managed adults on a project can tell you: working together is not always straightforward.

One of the fundamental tasks for early childhood educators is to teach children to cooperate, not just to keep things running smoothly in the classroom, but because it’s a life skill that prepares them for collaboration in their daily lives, in school and in the workforce.

Researchers at the University of Washington’s Institute for Learning & Brain Science (I-LABS) have been studying the effects of synchronized movements on social interactions among young children for years and it turns out that synchrony enhances cooperation. A study published in 2024 by I-LABS in the journal Nature shows that the simple act of moving in time with each other can promote prosocial behaviors, such as helping, sharing and empathizing.

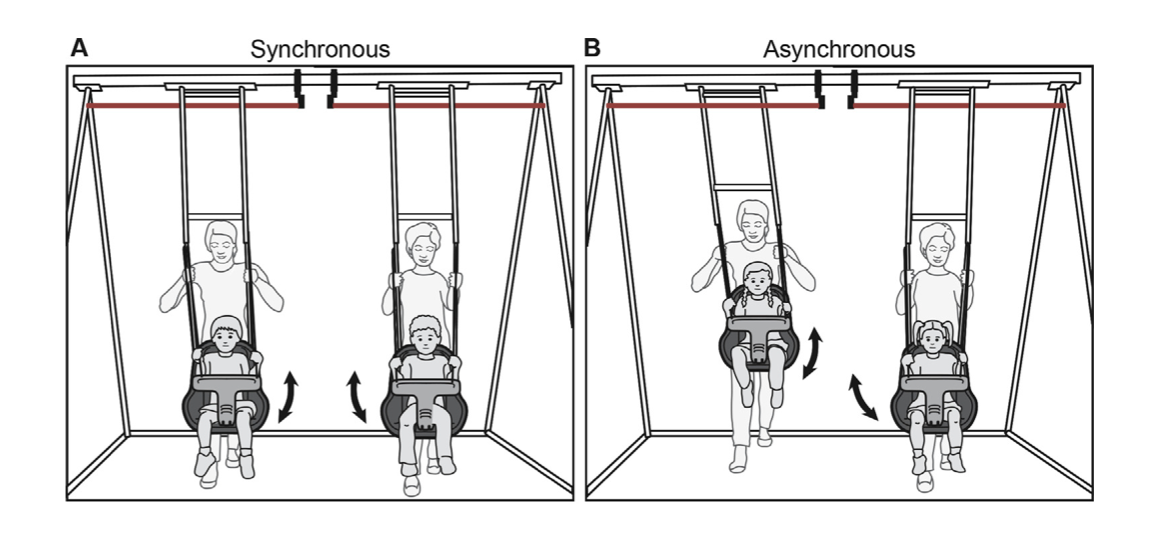

The study, which analyzed how a group of 4-year-olds cooperated with each other after a synchronous exercise, was authored by Tal-Chen Rabinowitch, a researcher at I-LABS who is now director of the Music & Social Development Lab at Israel’s University of Haifa, and Andrew Meltzoff, co-director of I-LABS. Researchers built a swing set that enabled two children to swing in unison in precisely controlled cycles of time. This study was set up so the children could see each other’s silhouette but not their facial expressions. The purpose was to determine if the synchronized movement itself, rather than facial or emotional cues stimulated prosocial behavior.

Pairs of children who were strangers to each other were randomly assigned to one of three separate groups: one that swung together in precise time, one that swung together but not in time, and another that didn’t swing at all. After the swinging exercise, the pairs participated in a series of tasks to evaluate their cooperation. One was a “give and take” activity that involved passing objects back and forth to each other through a puzzle-like device. Another was a computer game that required the children to push buttons simultaneously to see a cute cartoon figure pop up.

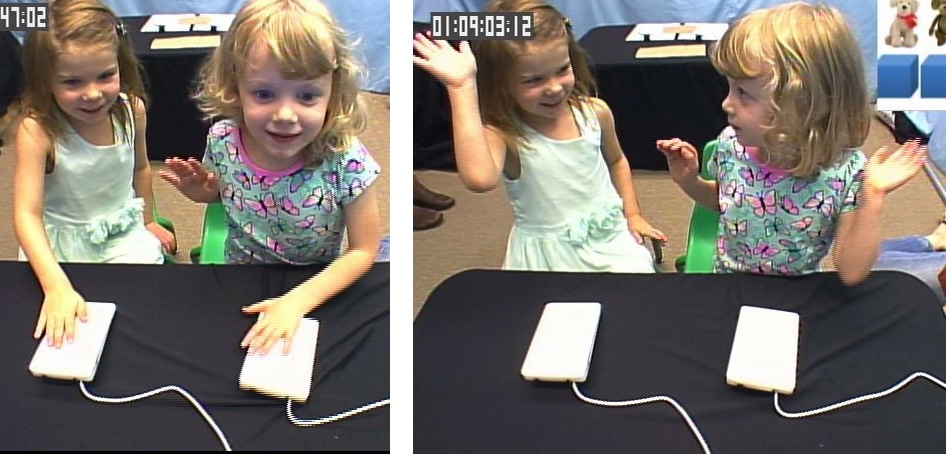

The researchers found that the children who swung in unison completed the tasks faster, indicating better cooperation than children who had swung out of sync or hadn’t swung at all. A surprise for Rabinowitch was a strategy the children came up with to synchronize their button-pushing. The strategy was never modeled to them but arose spontaneously in many of the pairs.

“They raised their hands above the button and signaled each other with these exaggerated motions just before the task, like, ‘OK. Are you watching? I’m going to do it, … now,’” Rabinowitch said. “The kids in the synchronous condition did it much more and came up with it more quickly. It’s interesting because it shows that not only were they better at cooperating, but they were also motivated to do so. The signaling made the task better.”

The study built upon two earlier investigations on synchrony and peer cooperation for preschoolers conducted by Rabinowitch. The distinct takeaway from the most recent study is the indication that, stripped of all the other elements of music, rhythm alone is sufficient to spark cooperation between children who moved together.

“It doesn’t even have to take a long time,” said Rabinowitch. “Just a couple of minutes doing an activity in sync with each other signals, ‘We’re together. We’re on the same page.’” Being in sync together enhances social interaction in positive ways.

“They could drum together, swing together, tap or dance together,” Rabinowitch said. “There’s no difference, as long as the children are aware of themselves moving in synchrony with each other. Knowing they are on the same page has a positive effect on their cooperative behavior, and the kids feel closer to each other.”

Rabinowitch, a classically trained flutist, became interested in the connection between music and social behavior as an undergraduate psychology student when she volunteered with children with physical and emotional disabilities and saw how music influenced their emotional communication and social interactions. She wrote her doctoral dissertation on how music interaction enhances empathy in children.

“When I did that research,” she said, “I noticed that I was always going back to playing rhythm games with them. I felt that there was something in the rhythm, in the synchrony itself that made a difference and that taught them something about how to communicate and listen. So, I continued in my postdoc to study synchrony specifically.”

Rabinowitch said many studies on the effect of music in creating cooperation among adults have been conducted and the results are the same. In a paper she authored in 2020, about whether music can effect social change, she writes that music has accompanied human civilization since its beginning and likely played an important role in forging human social behavior.

Music has a lot of potential to foster cooperation, Rabinowitch said. “Music has an ability that’s much more than just synchrony … It’s social glue,” she said.

“It’s this incredibly simple mechanism. … We’re just doing the same thing at the same time.” This mechanism can support all ages, she said. “It works with adults, it works with kids, it even works with babies. A study of 14-month-old toddlers showed that being bounced in synchrony enhanced their helping behavior,” she added.

Though there is still much to be understood about the mechanisms that link music and social behaviors, Rabinowitch’s studies underscore how uncomplicated, simple and profound it can be to bring people together. She isn’t suggesting a swing in every office, or drum circles in every school. Nor is she saying that synchronous movement is the answer to world peace. But it might be a start.

“I would love to say something stronger about politics, about how this could be used in very different contexts in the longer term. But I’m not confident enough of the science to say that yet. It is something one can dream about,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter