How Districts in Georgia, Maryland and D.C. Are Raising Reading Proficiency

Wakelyn: Research on 260 districts in 35 states found 3rd-grade reading scores rose in each of the last 3 years. What 3 of them are doing right.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

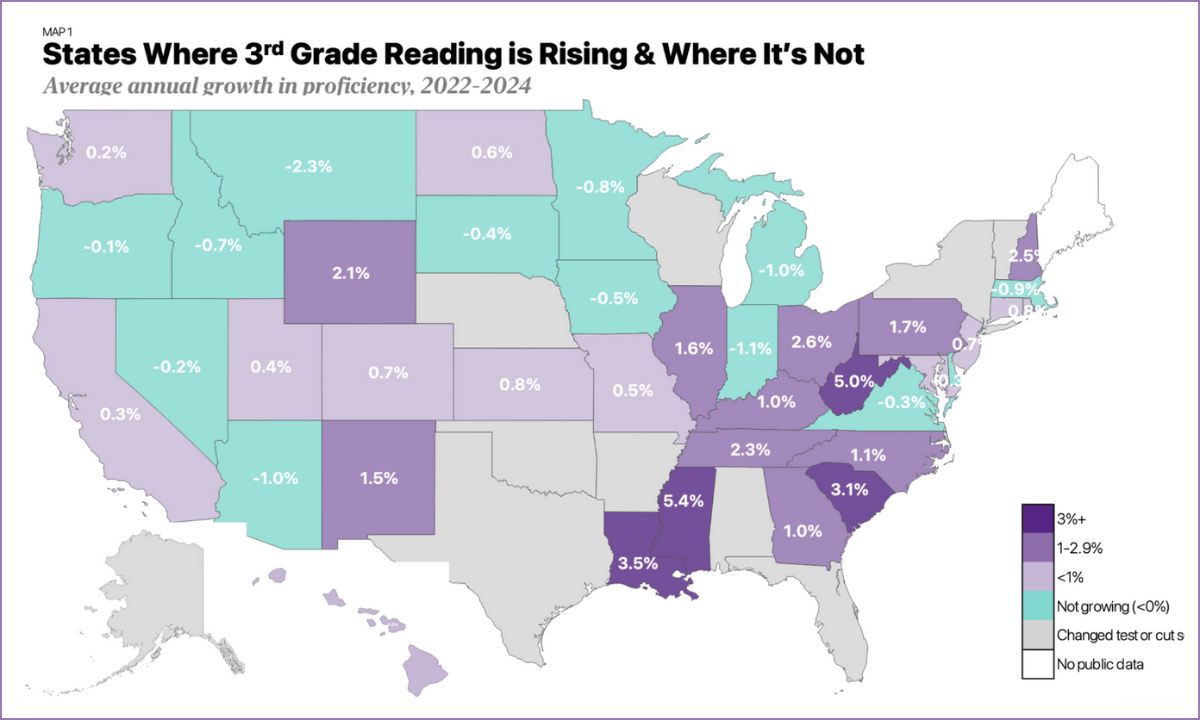

As summer approaches, district leaders will spend part of their vacation strategizing how to improve reading and writing achievement. The news this year has remained grim: NAEP fourth-grade scores in 2024 fell below 2022 levels and are a half-grade lower than they were before the pandemic. An analysis of third grade reading proficiency across 35 states by Upswing Labs, a nonprofit that works with districts and states to improve literacy, shows most schools are stalled, with average annual gains of less than a 1 percentage point.

Yet there are pockets of progress. Our new report, “Dynamic Districts and States: Where and How Literacy Is Improving (2025),” identified 260 school districts in which early reading proficiency rates have grown by 3 to 4 percentage points a year for the last three years. What are they doing differently that the rest might learn from?

Three districts in particular merited a closer look, as they represent a mix of sizes and starting points: Marietta City in the Atlanta suburbs; Allegany County, at the edge of the Appalachian Mountains in Maryland; and DC Prep, a K-8 public charter school network.

The project to identify dynamic districts across the country began with this goal: To reignite growth, districts are going to need to move past generic advice about what makes “effective schools” and understand more about specific strategies to improve literacy. All three districts profiled had been deeply dissatisfied with their students’ performance in reading and writing, diagnosed their internal challenges and began implementing coherent responses over several years.

Leaders in these districts did not start their literacy initiatives by creating a vision. Instead, they asked themselves and their teachers a version of this question: “What’s our most important problem, and how do we solve it?” The answer: through no fault of their own, was that most teachers don’t have a deep enough grasp of all elements of evidence-based reading instruction.

The districts launched deep, extended professional learning for all elementary teachers over two to three years. Marietta City trained teachers with Top Ten Tools, a set of mini-courses on core elements of literacy and how to teach them, then added a year of training with Writing Revolution, a set of courses on teaching expository writing. In 2020, Allegany County began a two-year engagement with LETRS, to help teachers master the basics of reading and writing instruction — phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

All three districts reconfigured and expanded time for literacy instruction. DC Prep extended its literacy period to 1 hour and 45 minutes and added a second teacher who provides targeted help at students’ desks instead of pulling them out of class for separate instruction. Allegany extended instruction to two hours and added 30 minutes for small-group interventions and enrichment.

Marietta redesigned its daily schedule so every student now receives roughly two to three hours of literacy instruction every day. Ninety minutes is dedicated to whole-class reading that weaves in grade-level science and social studies texts. There’s also 20 to 30 minutes of explicit phonics and word-study practice, and 30 to 60 minutes of small-group work where teachers target the skills individual students still need to develop.

[inline_story url=”https://www.the74million.org/article/teaching-science-reading-together-yields-double-benefits-for-learning/”The districts also changed how they staff schools. Marietta hired reading specialists who work with students in small groups of 10 across eight schools. Allegany redefined the role of literacy coach to provide teachers with more direct feedback about how well they deliver instruction to their classes. DC Prep converted the assistant principal position into a full-time instructional-coaching role. These leaders now run collaborative planning sessions and provide teachers with ongoing, in-class feedback.

Both Marietta and Allegany improved the quality of their K-5 language arts curricula. Marietta dropped giving students books they could already read — a popular practice that hasn’t been found to facilitate learning — and switched to Wit and Wisdom and a skills-based foundational class. Allegany stopped using Treasures and switched to Core Knowledge Language Arts. Both are highly rated by independent reviewers and are designed to build a deep and wide knowledge base using grade-level texts in science, history, literature and the arts.

Finally, they’ve refined assessments and how they use the results. While they dedicate time to phonics every day, these districts were clear that not every problem is a phonics problem. DC Prep’s data showed some small groups overemphasized foundational skills and needed more close reading, a technique of carefully analyzing a passage to understand what it means. In Allegany, test data pointed to a need to work more carefully on students’ reading fluency, not decoding.

This summer, Upswing Labs will begin more intensive case study research in eight more of the dynamic districts. The actions summarized here — engaging educators in deep professional learning, expanding the amount of time for teaching reading, changing what literacy coaches do and improving the quality of curricula and diagnostic testing — clarify what to do. District instructional leaders also need insight on how to do it.

The research will also examine three types of rural districts more closely, as they make up a large share of the 260 districts identified in the report. Researchers will focus on communities of African-American students in the South, Hispanic students in agricultural communities in California and Texas and evangelical churchgoers in Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee.

Finally, the case studies will explore whether the best tactics shift as a district climbs the performance ladder — echoing McKinsey’s finding that the moves that lift proficiency for students near the bottom are often different from those that propel midrange improvement.

With sharper insight into both what works and how to implement it, more districts will be able to chart a path to improved literacy achievement.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)