Most Students Say They’re Not ‘Math People,’ RAND Survey Finds

A newly released poll shows huge numbers of middle and high schoolers zoning out during math class.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Nearly one in three students in middle and high school say they’ve never felt like a “math person,” according to newly released polling from the RAND Corporation. Another 25% said they used to feel at home in the subject, but don’t any longer.

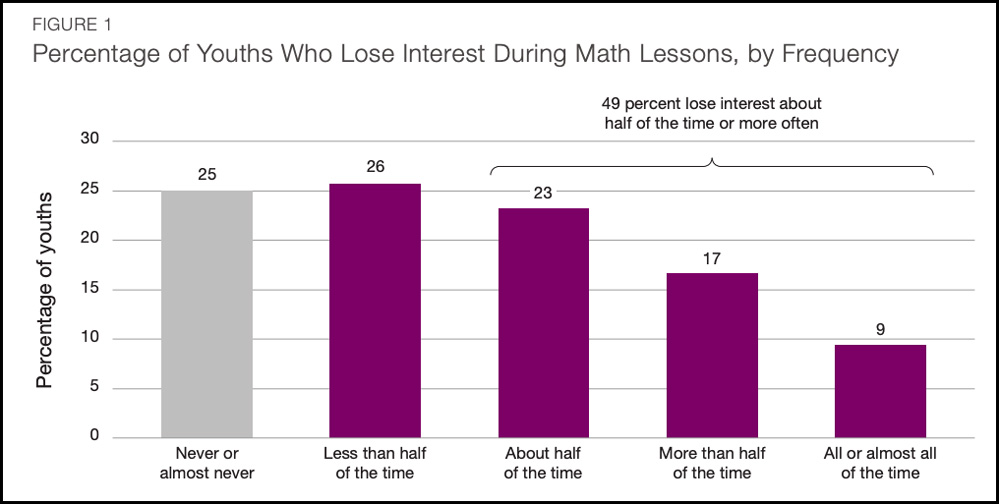

The survey, published by the research firm Tuesday, also points to pervasive trends of disengagement and boredom among more than 400 respondents in grades five through 12. The vast majority of students said they regularly lost interest in their math classes, and 49% said they tuned out at least half the time. By contrast, children who have identified as “math people” — even if only in the past — are much more likely to retain interest in their day-to-day lessons, along with those who feel they understand and enjoy the process of doing math.

Heather Schwartz, RAND’s vice president for education and labor and a co-author of the report, said that students’ self-conception as being detached from or uninvolved with math was likely worsened by the pandemic, which stifled understanding across a range of subjects while most of the poll’s participants were still in their foundational years of learning. The problem of post-COVID boredom is “endemic,” she added.

“It’s not just girls or boys or middle schoolers or high schoolers, it’s widespread,” Schwartz observed. “In terms of talking about post-COVID recovery and the lack thereof, this boredom is potentially one leading reason for the high levels of disengagement we’re seeing.”

Indeed, students from different backgrounds and age groups all reported high amounts of indifference to math. Girls were slightly more likely than boys to say their attention faded during math lessons at least half the time (53% versus 45%) — perhaps a reflection of a post-COVID pattern in which males have performed somewhat better in STEM subjects — but middle schoolers and high schoolers, along with white, Hispanic, and Black students, all said the same in roughly similar numbers.

In terms of talking about post-COVID recovery, this boredom is potentially one leading reason for the high levels of disengagement we’re seeing.

Heather Schwartz, RAND

Notably, among high schoolers who said they felt comfortable with math, most said they reached that realization in their elementary years. That claim dovetails with earlier findings, which have also placed the development of math attitudes in early childhood. The frequently reported phenomenon of math anxiety, as well as the gender gap in math skills, both tend to emerge as kids first explore the subject.

Meanwhile, only a small number of secondary school students who say they are math people developed that notion in high school, the poll shows.

Jon Star, an educational psychologist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, said in an email that it was particularly difficult to combat children’s belief that they may simply be unable to succeed in courses like algebra.

The work of persuasion may have become harder since the COVID-era, which drastically widened the gaps in academic performance and preparation in K–12 classrooms. While many of America’s top-performing students held their ground during the period of virtual learning, or even pulled ahead, their struggling schoolmates declined to levels of math achievement last seen decades ago. Middle school math teachers, who are responsible for helping their pupils transition from arithmetic to more challenging concepts, now have to differentiate their lessons to accommodate both high-flyers and those in need of serious remediation.

“To what extent should a sixth-grade teacher continue to work with students on the material from prior grades that they have not yet mastered, versus moving forward toward (pre)algebraic content?” Star wondered. “It is very hard to do both of these at the same time, yet each approach may increase boredom for some subset of students.”

There do exist gifted math teachers who possess so much charisma, energy, expertise, and passion that they can make the subject come alive. However, they are a rarity.

Jason Roberts, Math Academy

Jason Roberts is the co-founder of Math Academy, an online learning platform that offers users personalized instruction developed partly through the use of artificial intelligence. In an email, he noted that there was nothing surprising about large numbers of students being bored in math class. Still, he said, cynicism and discouragement could be overcome through support from families and teachers, and no shortcuts existed to the satisfaction of mastering complex ideas.

In particular, he wrote, teachers who are passionate about STEM subjects can play a role as enthusiastic evangelists.

“There do exist gifted math teachers who possess so much charisma, energy, expertise, and passion that they can make the subject come alive, even for students who never gave it a second thought,” Roberts remarked. “However, they are a rarity, and this isn’t something that can be acquired by attending a few professional development sessions or even one-on-one coaching.”

Even hiring qualified math teachers has become a major difficulty since 2020, with certified instructors commanding a premium in an ultra-tight labor market. According to one poll, one-quarter of all K–12 teachers themselves experience math anxiety.

Schwartz argued that the only way to conquer that discomfort and bring more expertise into the classroom was to change the way teachers prepare for the job. More need to be trained explicitly as math teachers, with a heavy focus on content knowledge, while still serving as trainees, she concluded.

“Frankly, I think it’s got to involve more training for teachers in the content, especially during teacher prep. They should be subject-matter experts, not just pedagogical experts.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)